Tribunals

Tribunals in India

The original Constitution did not include provisions for tribunals, but the 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 introduced Part XIV-A, focusing on tribunals, comprising two key articles: Article 323A for administrative tribunals and Article 323B for tribunals addressing other matters.

Administrative Tribunals

Article 323A empowers Parliament to establish administrative tribunals to adjudicate disputes regarding the recruitment and conditions of service for individuals appointed to public services at the Center, state level, local bodies, public corporations, and other authorities. This provision effectively transfers these disputes from civil and high courts to administrative tribunals, aiming to provide quicker and more affordable justice for public servants.

Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT)

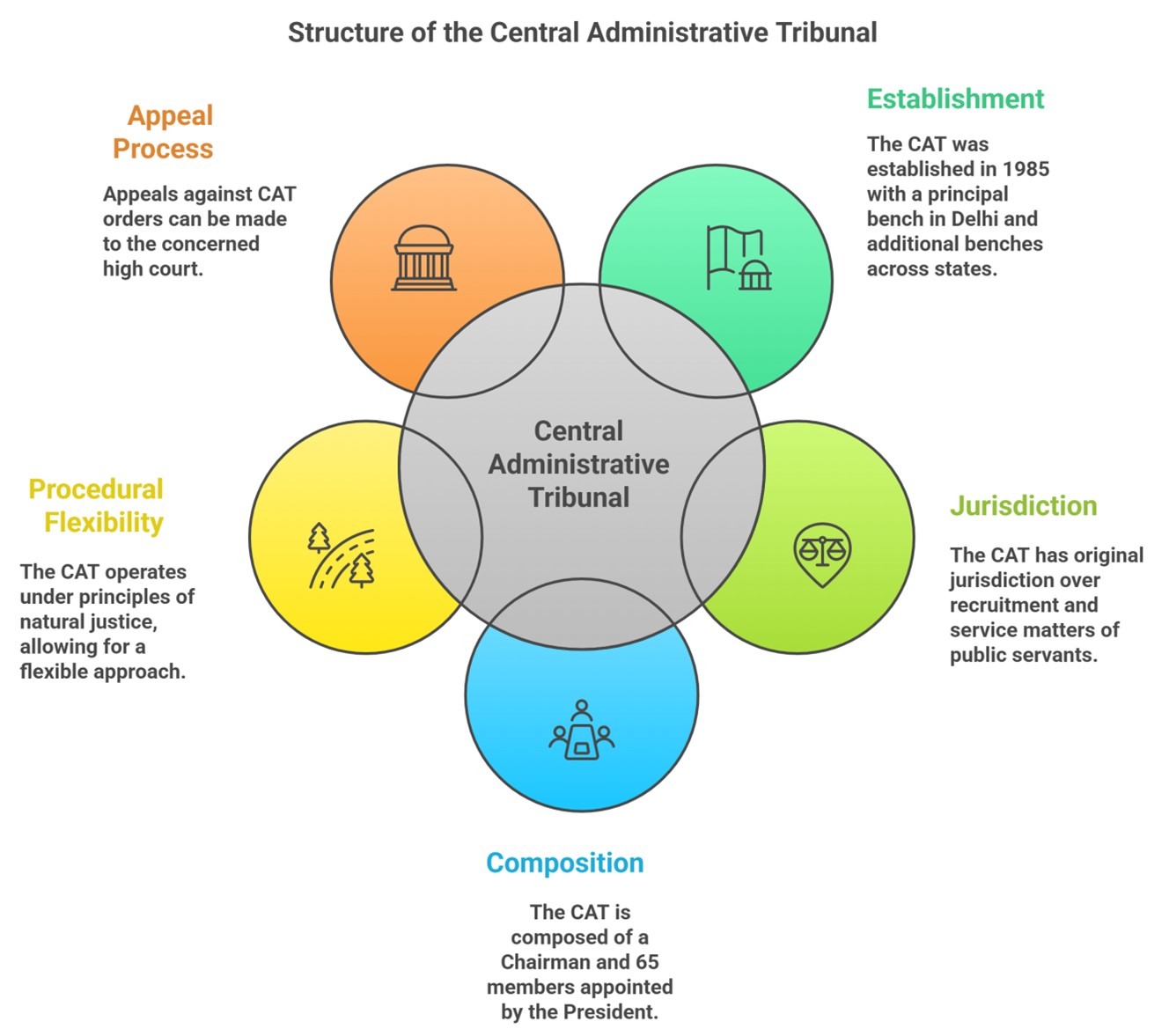

- Establishment: The Central Administrative Tribunal was established in 1985, with its principal bench in Delhi and various additional benches across states. As of now, it comprises 17 regular benches, including locations at Jaipur and Lucknow, along with circuit sittings in other high court locations.

- Jurisdiction: The CAT holds original jurisdiction over recruitment and service matters related to public servants. Its jurisdiction covers all-India services, Central civil services, civil posts under the Center, and civilian employees in the defense services. Notably, it does not cover members of the defense forces or personnel associated with the Supreme Court or Parliament.

- Composition: Initially, the CAT consisted of a Chairman, Vice-Chairman, and members. As per the Administrative Tribunals (Amendment) Act, 2006, the Vice-Chairman role was removed. Currently, the CAT has a Chairman and 65 members, drawn from judicial and administrative backgrounds, appointed by the President based on the recommendations of a high-powered selection committee led by a sitting Supreme Court judge.

- Procedural Flexibility: The CAT is not bound by the Civil Procedure Code of 1908 but operates according to the principles of natural justice, allowing for a more flexible approach. A nominal fee of ₹50 is charged for applications, and applicants can represent themselves or hire a lawyer.

- Appeal Process: Originally, appeals from the CAT could only go to the Supreme Court. However, the Chandra Kumar case (1997) deemed this limitation unconstitutional, establishing that appeals against CAT orders can be made to the concerned high court, emphasizing that judicial review is integral to the Constitution’s basic structure.

State Administrative Tribunals (SAT)

The Administrative Tribunals Act of 1985 also allows the establishment of State Administrative Tribunals (SATs) at the request of state governments. As of 2019, SATs exist in several states, including Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Odisha, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, and Kerala. However, some have been abolished and later reestablished, such as the Himachal Pradesh SAT.

- Jurisdiction: Similar to the CAT, SATs exercise original jurisdiction over recruitment and service matters concerning state government employees.

- Appointment of Officials: The Chairman and members of the SATs are appointed by the President after consultation with the respective state governor.

- Joint Administrative Tribunals (JAT): The Act also permits the formation of joint administrative tribunals for multiple states, with jurisdiction and powers akin to individual administrative tribunals.

The introduction of administrative tribunals through amendments to the Constitution reflects a significant shift towards specialized institutions to enhance the efficiency and accessibility of justice for public servants. Through structures like the CAT and SATs, the legal process surrounding service disputes has become more streamlined, upholding the rights of civil servants while ensuring governance efficiency.

Tribunals for Other Matters

Under Article 323B of the Indian Constitution, Parliament and state legislatures are empowered to establish tribunals for the resolution of disputes in various key areas, including:

- Taxation

- Foreign exchange, import, and export

- Industrial and labor matters

- Land reforms

- Ceiling on urban property

- Elections to Parliament and state legislatures

- Foodstuffs

- Rent and tenancy rights

Differences Between Article 323A and Article 323B

Article 323A and Article 323B differ in several important aspects:

1. Scope of Matters:

- Article 323A relates specifically to the establishment of tribunals for public service matters.

- Article 323B allows for the establishment of tribunals covering a broader range of issues, including those mentioned above.

2. Establishment Authority:

- Article 323A allows only Parliament to establish tribunals.

- Article 323B enables both Parliament and state legislatures to create tribunals concerning matters within their legislative competence.

3. Tribunal Hierarchy:

- Under Article 323A, only a single tribunal can be established at the Centre and one for each state, with no hierarchy among them.

- In contrast, Article 323B permits the creation of a hierarchical structure of tribunals.

Judicial Review of Tribunal Orders

In the Chandra Kumar case (1997), the Supreme Court declared provisions that excluded the jurisdiction of high courts and the Supreme Court over these tribunals unconstitutional. This ruling affirmed that judicial remedies must be available against orders issued by these tribunals, upholding the principle of judicial review and ensuring access to justice.

Name and Jurisdiction of Benches of the Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT)

The CAT operates through various benches across India, each with specified territorial jurisdiction. Below is a summary of the benches:

Sl. No. | Bench | Territorial Jurisdiction |

1 | Principal Bench, Delhi | Delhi |

2 | Allahabad Bench | Uttar Pradesh (except districts covered by Lucknow Bench) and Uttarakhand |

3 | Lucknow Bench | Uttar Pradesh (except districts covered by Allahabad Bench) |

4 | Cuttack Bench | Odisha |

5 | Hyderabad Bench | Andhra Pradesh and Telangana |

6 | Bangalore Bench | Karnataka |

7 | Madras Bench | Tamil Nadu and Puducherry |

8 | Ernakulam Bench | Kerala and Lakshadweep |

9 | Bombay Bench | Maharashtra, Goa, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, and Daman and Diu |

10 | Ahmedabad Bench | Gujarat |

11 | Jodhpur Bench | Rajasthan (except districts covered by Jaipur Bench) |

12 | Jaipur Bench | Rajasthan (except districts covered by Jodhpur Bench) |

13 | Chandigarh Bench | Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Chandigarh, Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh |

14 | Jabalpur Bench | Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh |

15 | Patna Bench | Bihar and Jharkhand |

16 | Calcutta Bench | West Bengal, Sikkim, and Andaman and Nicobar Islands |

17 | Guwahati Bench | Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Tripura, Nagaland, Mizoram, and Arunachal Pradesh |

Circuit Sittings of Benches of CAT

The CAT’s benches also hold circuit sittings to enhance access to justice:

Sl. No. | Bench | Circuit Sittings Held |

1 | Allahabad Bench | Nainital |

2 | Calcutta Bench | Port Blair, Gangtok |

3 | Chandigarh Bench | Shimla, Jammu, Srinagar |

4 | Madras Bench | Puducherry |

5 | Guwahati Bench | Shillong, Itanagar, Kohima, Agartala, Imphal, Aizawl |

6 | Jabalpur Bench | Indore, Gwalior, Bilaspur |

7 | Bombay Bench | Nagpur, Aurangabad, Panaji |

8 | Patna Bench | Ranchi |

9 | Ernakulam Bench | Lakshadweep |