Fundamental Rights

Fundamental Rights are enshrined in Part III of the Indian Constitution, covering Articles 12 to 35. The framers of the Constitution drew inspiration from the United States Constitution, specifically the Bill of Rights. Part III of the Constitution is often referred to as the “Magna Carta of India” due to its comprehensive and detailed list of justiciable rights.

These rights are considered more extensive than those found in the constitutions of many other countries, including the U.S. Fundamental Rights are guaranteed to all individuals regardless of discrimination, promoting the equality of all, preserving individual dignity, and supporting the public interest and national unity.

The purpose of these rights is to uphold the principles of political democracy and prevent the establishment of authoritarian rule. They safeguard individual liberties and freedoms against violations by the state, acting as checks on potential executive tyranny and arbitrary laws enacted by the legislature. Essentially, they aim to establish “a government of laws and not of men.”

The term “Fundamental Rights” reflects their guaranteed protection by the Constitution, which serves as the fundamental law of the land. These rights are also termed “fundamental” because they are crucial for the all-round development of individuals—material, intellectual, moral, and spiritual.

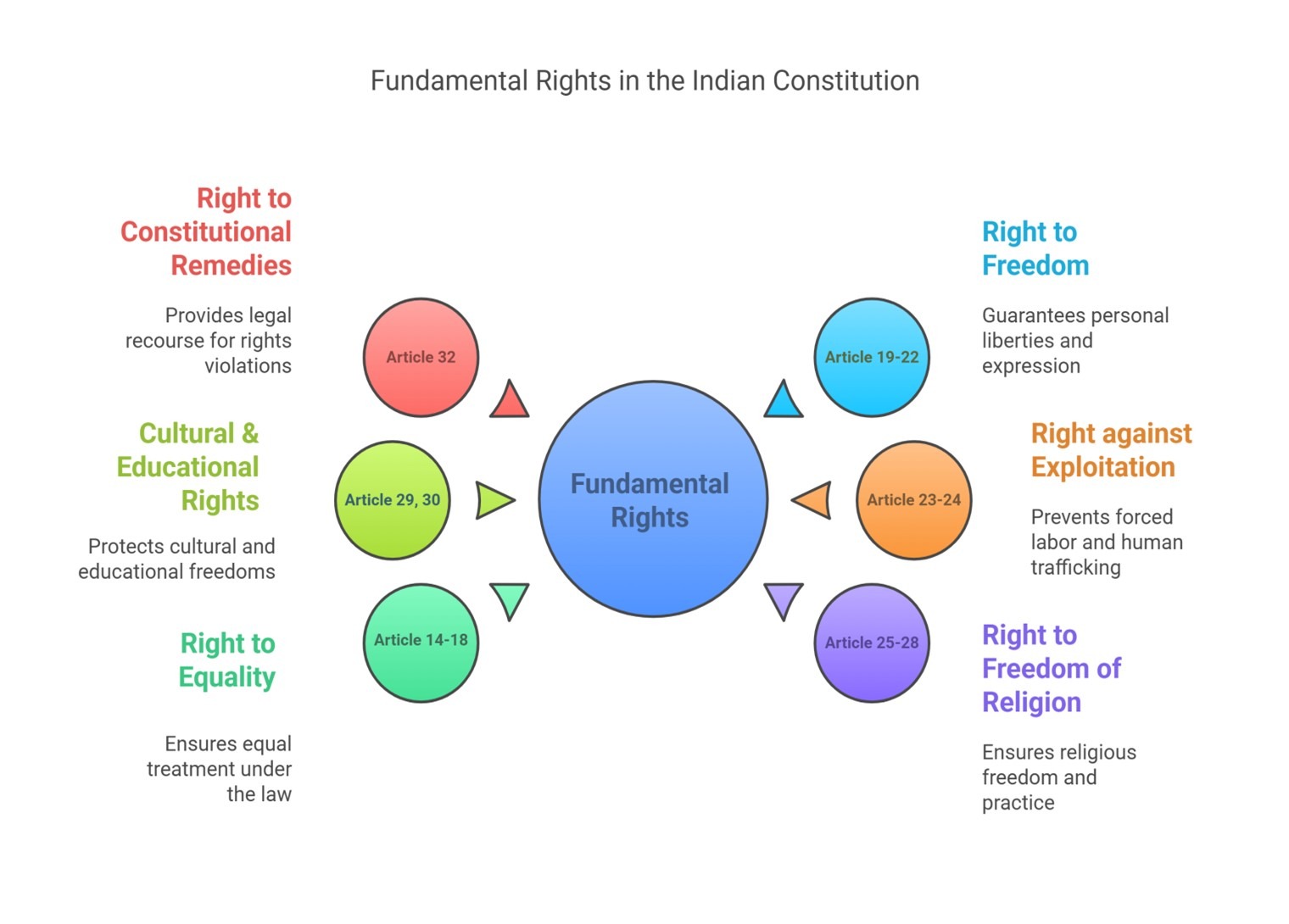

Initially, the Constitution recognized seven Fundamental Rights:

- Right to Equality(Articles 14–18)

- Right to Freedom(Articles 19–22)

- Right Against Exploitation(Articles 23–24)

- Right to Freedom of Religion(Articles 25–28)

- Cultural and Educational Rights(Articles 29–30)

- Right to Property(Article 31)

- Right to Constitutional Remedies(Article 32)

However, the Right to Property was removed from the list of Fundamental Rights by the 44th Amendment Act in 1978, and is now recognized as a legal right under Article 300-A in Part XII of the Constitution. As a result, there are currently six Fundamental Rights in the Constitution.

Features of Fundamental Rights

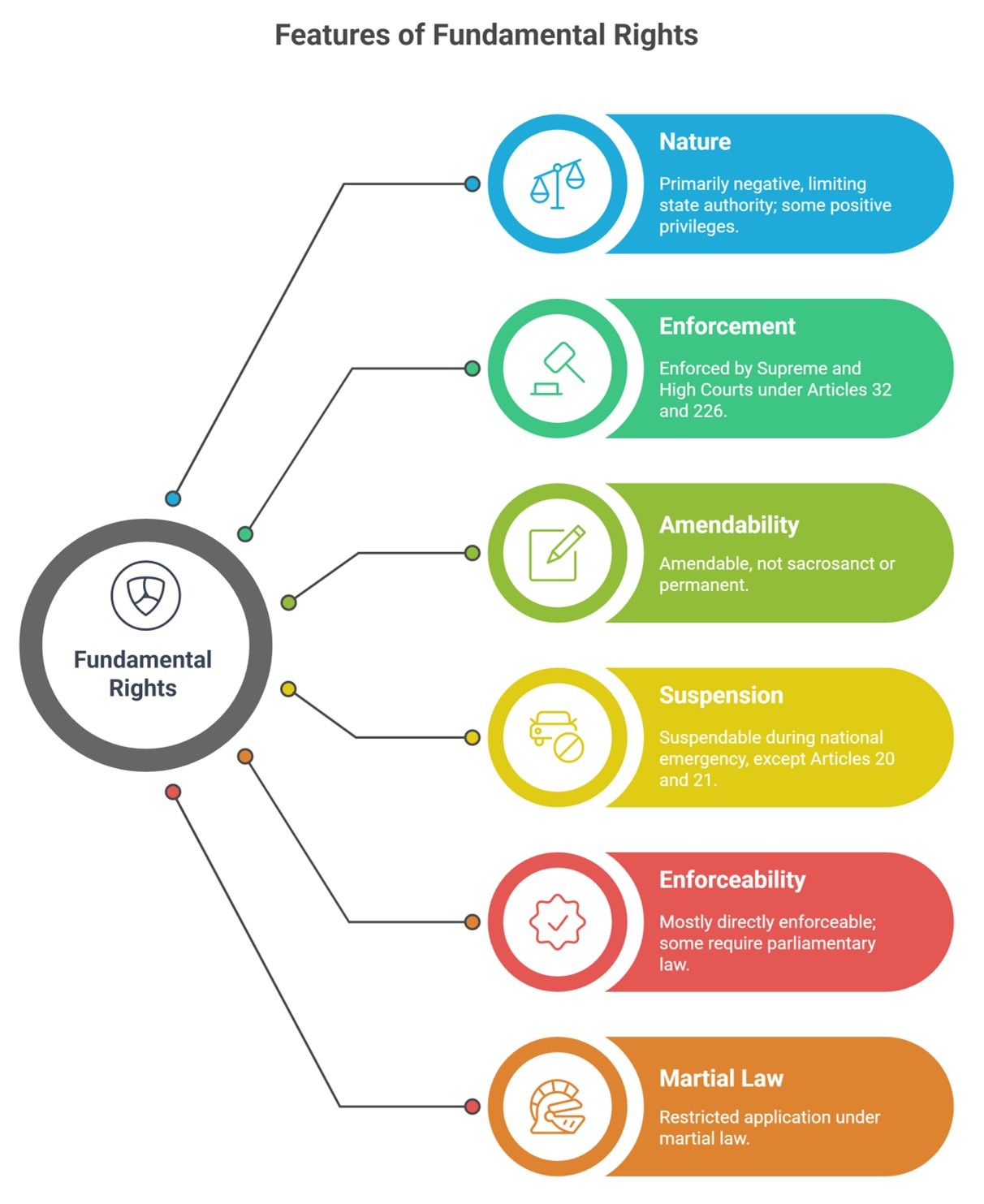

The Fundamental Rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution are characterized by several key features:

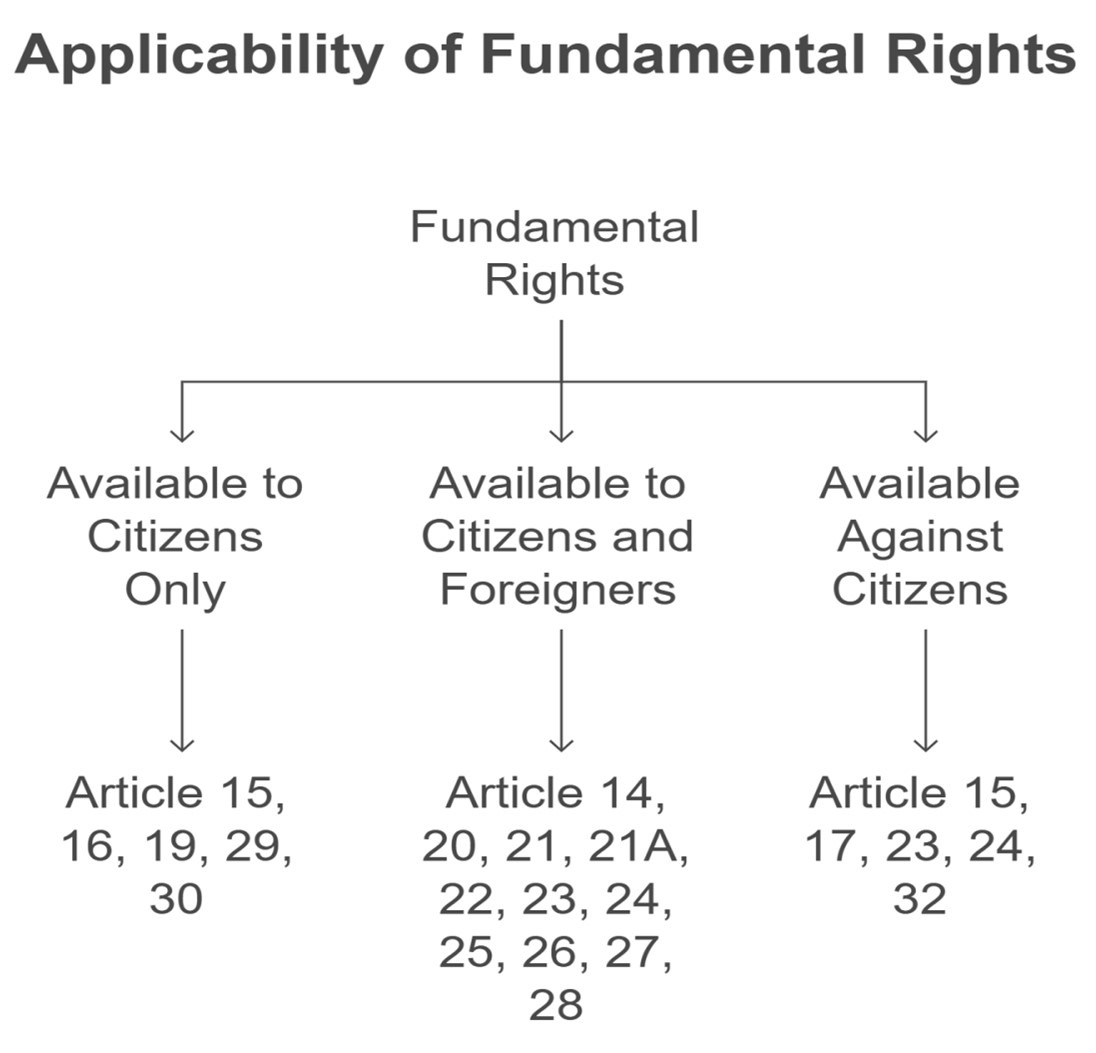

- Availability to Different Persons: Some Fundamental Rights are exclusive to citizens, while others are accessible to all individuals, including foreigners and legal entities like corporations and companies.

- Not Absolute but Qualified: These rights are not absolute and can be subjected to reasonable restrictions imposed by the state. The courts determine whether such restrictions are reasonable, aiming to balance individual rights with societal interests and ensuring a balance between personal liberty and social control.

- Protection Against Arbitrary Action: All Fundamental Rights protect against arbitrary actions by the state. Additionally, certain rights also provide protection against actions taken by private individuals.

- Negative and Positive Rights: Some rights are negative in nature, meaning they limit the authority of the state, while others are positive, conferring specific privileges on individuals.

- Justiciable Rights: Fundamental Rights are enforceable through the courts, allowing individuals to approach the judiciary for their enforcement if violated.

- Defended by the Supreme Court: These rights are guaranteed by the Supreme Court. An aggrieved individual can directly approach the Supreme Court without needing to appeal to the High Courts.

- Not Permanent or Sacrosanct: While these rights are protected, they are not unchangeable. Parliament can curtail or repeal them through a constitutional amendment, not through ordinary legislation, but such changes must not affect the ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution.

- Suspension During National Emergency: Fundamental Rights can be suspended during a National Emergency, except for the rights guaranteed by Articles 20 and 21. Additionally, the rights under Article 19 can only be suspended during an external emergency (war or aggression), not during an internal emergency (armed rebellion).

- Limitations on Operation: The operation of these rights is limited by certain articles—Article 31A (which saves laws regarding estate acquisition), Article 31B (validating specific acts in the 9th Schedule), and Article 31C (which safeguards laws that give effect to certain directive principles).

- Applicability to Armed Forces: The application of Fundamental Rights can be restricted or abrogated for members of the armed forces, paramilitary forces, police, intelligence agencies, and similar services (Article 33).

- Restrictions During Martial Law: Fundamental Rights can also be restricted while martial law is in force. Martial law refers to military rule imposed to restore order under exceptional circumstances, as stated in Article 34, and is distinct from a national emergency.

- Enforcement: Most rights are directly enforceable (self-executory), while a few require laws made by Parliament for their enforcement. Such laws must be enacted by Parliament to ensure uniformity across the country (Article 35).

These features highlight the significance of Fundamental Rights in protecting individual liberties while also allowing for the governance necessary to maintain social order and public interest.

Definition of State

In the context of the Indian Constitution, the term “State” is used in various provisions related to Fundamental Rights. Article 12 specifically defines “State” for the purposes of Part III of the Constitution. According to this article, the term “State” comprises the following entities:

- Government and Parliament of India: This refers to the executive and legislative organs of the Union Government.

- Government and Legislature of States: This includes the executive and legislative organs of the individual state governments.

- Local Authorities: This encompasses municipalities, panchayats, district boards, improvement trusts, and other similar local governing bodies.

- Other Authorities: This category includes both statutory and non-statutory authorities, such as organizations like the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC), Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), and Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL).

The definition of “State” is thus broad and inclusive, ensuring that all agencies and bodies acting on behalf of the government are encompassed within this term. Actions taken by these agencies can be contested in court if they are believed to violate Fundamental Rights.

Additionally, the Supreme Court has clarified that even private bodies or agencies functioning as instruments of the State fall under the definition of “State” as outlined in Article 12. This broad interpretation allows for comprehensive protection of Fundamental Rights against various forms of authority.

Laws Inconsistent with Fundamental Rights

Article 13 of the Indian Constitution states that any law that contradicts or undermines any Fundamental Rights shall be declared void. This article explicitly establishes the principle of judicial review, granting the Supreme Court (under Article 32) and the High Courts (under Article 226) the authority to declare laws unconstitutional and invalid if they violate Fundamental Rights.

The definition of “law” in Article 13 includes a broad range of legal provisions, encompassing the following:

- Permanent Laws: These are laws enacted by the Parliament or state legislatures.

- Temporary Laws: This category includes ordinances issued by the President or state governors.

- Statutory Instruments: These pertain to delegated legislation, such as orders, bye-laws, rules, regulations, or notifications.

- Non-legislative Sources of Law: This includes customs or usages that have the force of law.

As a result, not only legislative enactments but also the aforementioned types of laws can be challenged in court for violating Fundamental Rights and can, therefore, be declared void.

Moreover, Article 13 specifies that constitutional amendments do not fall within the definition of “law” and, as such, cannot be challenged. However, in the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case (1973), the Supreme Court ruled that a constitutional amendment may indeed be subject to challenge if it infringes upon a Fundamental Right that is considered part of the “basic structure” of the Constitution, thus making it void.

This ruling underscore the significance of Fundamental Rights in the constitutional framework and affirms the judiciary’s role in protecting those rights against any potential infringement through legislation or constitutional amendments.

Fundamental Rights at a Glance

Here is an overview of the Fundamental Rights enshrined in the Indian Constitution, categorized by their respective articles:

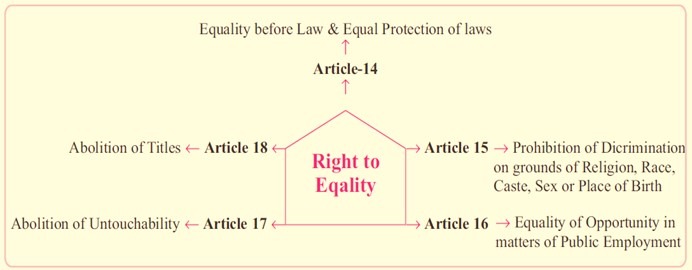

1. Right to Equality (Articles 14–18)

- Article 14: Equality before law and equal protection of laws.

- Article 15: Prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

- Article 16: Equality of opportunity in matters of public employment.

- Article 17: Abolition of untouchability and prohibition of its practice.

- Article 18: Abolition of titles, except for military and academic titles.

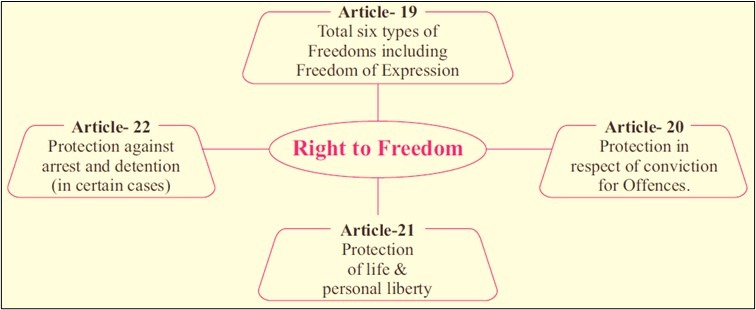

2. Right to Freedom (Articles 19–22)

- Article 19: Protection of six freedoms, including:

- (i) Freedom of speech and expression

- (ii) Freedom of assembly

- (iii) Freedom of association

- (iv) Freedom of movement

- (v) Freedom of residence

- (vi) Freedom of profession

- Article 20: Protection against conviction for offenses.

- Article 21: Protection of life and personal liberty.

- Article 21A: Right to elementary education.

- Article 22: Protection against arrest and detention in certain cases.

- Article 19: Protection of six freedoms, including:

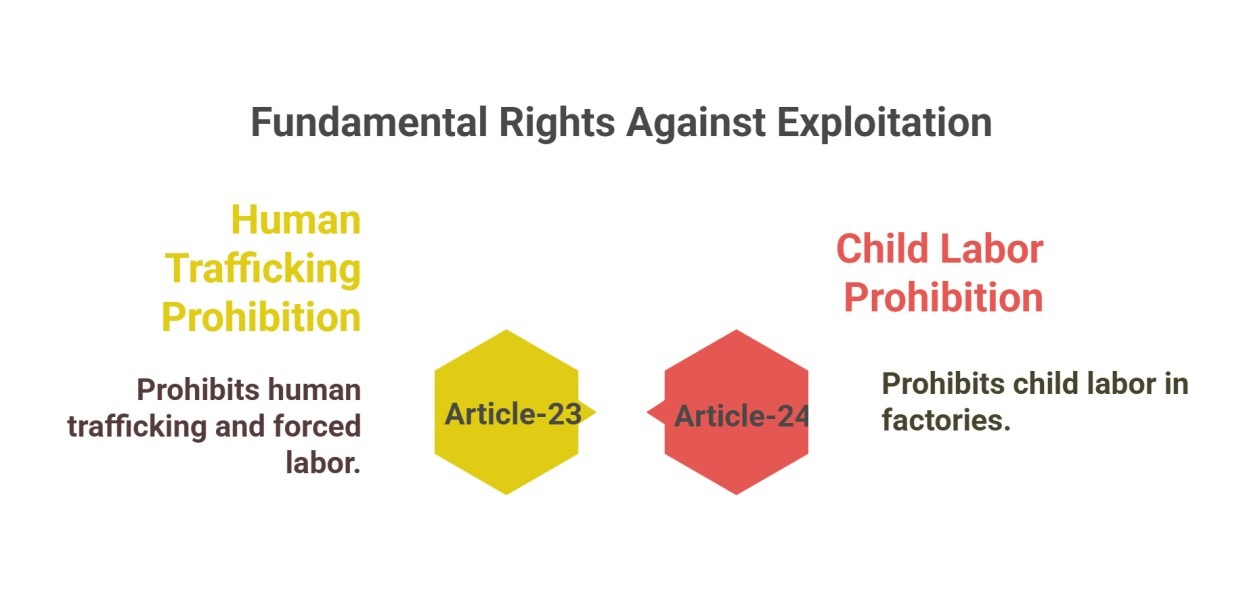

3. Right Against Exploitation (Articles 23–24)

- Article 23: Prohibition of trafficking in human beings and forced labor.

- Article 24: Prohibition of the employment of children in factories and hazardous occupations.

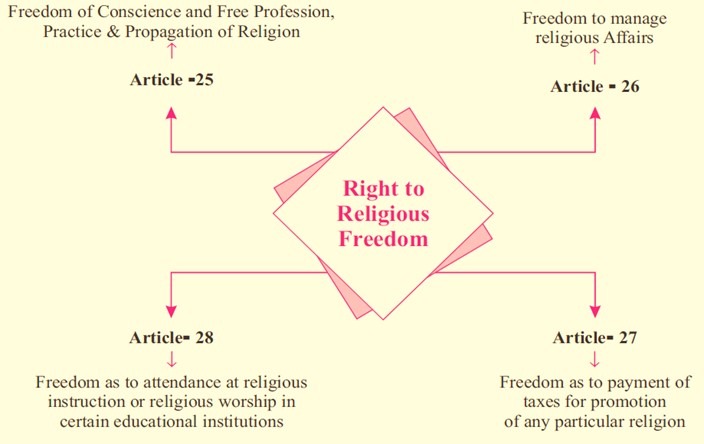

4. Right to Freedom of Religion (Articles 25–28)

4. Right to Freedom of Religion (Articles 25–28)

- Article 25: Freedom of conscience and the right to profess, practice, and propagate religion.

- Article 26: Freedom to manage religious affairs.

- Article 27: Freedom from taxation for the promotion of any religion.

- Article 28: Freedom from attending religious instruction or worship in certain educational institutions.

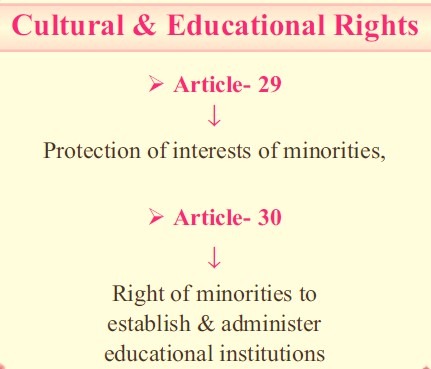

5. Cultural and Educational Rights (Articles 29–30)

- Article 29: Protection of the language, script, and culture of minorities.

- Article 30: Right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions.

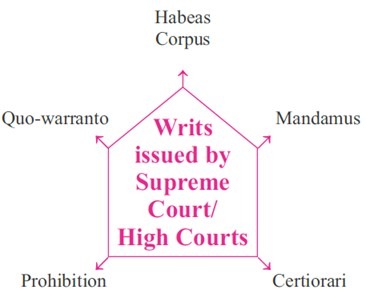

6. Right to Constitutional Remedies (Article 32)

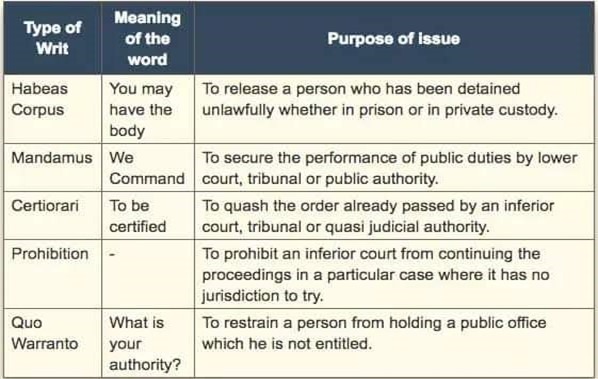

- Article 32: Right to approach the Supreme Court for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights, including the issuance of writs such as:

- (i) Habeas Corpus

- (ii) Mandamus

- (iii) Prohibition

- (iv) Certiorari

- (v) Quo Warranto

- Article 32: Right to approach the Supreme Court for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights, including the issuance of writs such as:

This overview elucidates the fundamental rights that safeguard individual freedoms and liberties in India, ensuring equality, justice, and protection from exploitation.

Fundamental Rights (FR) of Foreigners

The Fundamental Rights in India primarily apply to citizens, but certain rights are also accessible to foreigners (excluding enemy aliens). Below is a summary of Fundamental Rights categorized into those available only to citizens and those available to both citizens and foreigners:

Fundamental Rights Available Only to Citizens

- Prohibition of Discrimination: Protection against discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth (Article 15).

- Equality of Opportunity: Assurance of equality of opportunity in public employment (Article 16).

- Protection of Six Freedoms: Rights concerning freedom of:

(i) Speech and expression

(ii) Assembly

(iii) Association

(iv) Movement

(v) Residence

(vi) Profession (Article 19).

- Protection of Life and Personal Liberty: Right to life and personal liberty (Article 21).

- Right to Elementary Education: Right to receive elementary education (Article 21A).

- Right of Minorities: The right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions (Article 30).

Fundamental Rights Available to Both Citizens and Foreigners (Except Enemy Aliens)

- Equality Before Law: Assurance of equality before the law and equal protection of laws (Article 14).

- Protection Against Conviction: Protection in respect of conviction for offenses (Article 20).

- Protection of Life and Personal Liberty: Right to life and personal liberty (Article 21) is also available to foreigners.

- Protection Against Arrest and Detention: Protection against arrest and detention in certain cases (Article 22).

Rights Specific to Labor and Religion (Available to All):

- Prohibition of Human Trafficking: Prohibition of trafficking in human beings and forced labor (Article 23).

- Child Employment: Prohibition of employment of children in factories and other hazardous occupations (Article 24).

- Freedom of Religion:

Freedom of conscience and the right to profess, practice, and propagate religion (Article 25).

Freedom to manage religious affairs (Article 26).

Freedom from taxation for the promotion of any religion (Article 27).

Freedom from attending religious instruction or worship in certain educational institutions (Article 28).

This categorization illustrates the distinct framework for Fundamental Rights in India, highlighting the privileges afforded to citizens while ensuring some protections extend to non-citizens as well.

Right to Equality

1. Equality Before Law and Equal Protection of Laws

Article 14 of the Indian Constitution states that the State shall not deny any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India. This provision applies to all individuals, including both citizens and foreigners. The term “person” encompasses legal entities such as statutory corporations, companies, and registered societies.

The principle of “equality before law” has its roots in British law, while the concept of “equal protection of laws” is derived from the American Constitution. The former means:

(a) There are no special privileges for any person.

(b) All individuals are subject to the ordinary laws of the land as administered by regular courts.

(c) No individual, whether rich or poor, high or low, official or non-official, is above the law.

Conversely, “equal protection of laws” entails:

(a) Equal treatment in similar circumstances, both concerning privileges and legal liabilities.

(b) The same laws must apply to all persons in similar situations.

(c) Similar cases should be treated alike without discrimination.

Thus, while the first concept emphasizes the absence of privileges, the second focuses on equality of treatment. Both aim to establish a foundation of legal equality and justice.

The Supreme Court has determined that Article 14 does not apply when equals and unequals are treated differently. While it prohibits class legislation, it allows for reasonable classification of persons, objects, and transactions. However, this classification must not be arbitrary or artificial; it should be based on an intelligible criterion and a substantial distinction.

Rule of Law

The concept of “equality before law” is a fundamental aspect of the Rule of Law, as articulated by British jurist A.V. Dicey. His doctrine includes three essential components:

(i) Absence of Arbitrary Power: No individual can be punished without a breach of law.

(ii) Equality Before the Law: All citizens (rich or poor, high or low, official or non-official) are equally subject to the ordinary laws administered by regular courts.

(iii) Primacy of Individual Rights: In Dicey’s view, the Constitution arises from individual rights as defined and enforced by courts, rather than being the source of these rights.

In the Indian constitutional framework, the principles of “equality before law” and “equal protection of the laws” (as embodied in Article 14) are applicable and form an essential part of the legal system. However, the notion of a “primacy of individual rights” as a separate concept is not applicable in the same way. Instead, in India, the Constitution itself serves as the foundation for individual rights.

The Supreme Court has affirmed that the “Rule of Law,” as encapsulated in Article 14, constitutes a “basic feature” of the Constitution. This designation means that the principles of equality under the law cannot be altered or removed even through constitutional amendments. Therefore, the integrity of this fundamental aspect of governance is preserved, ensuring that all individuals are treated equally and justly under the law.

Exceptions to Equality

While the principle of equality before the law is fundamental in the Indian Constitution, it is not absolute and is subject to certain constitutional exceptions. Below are the key exceptions outlined:

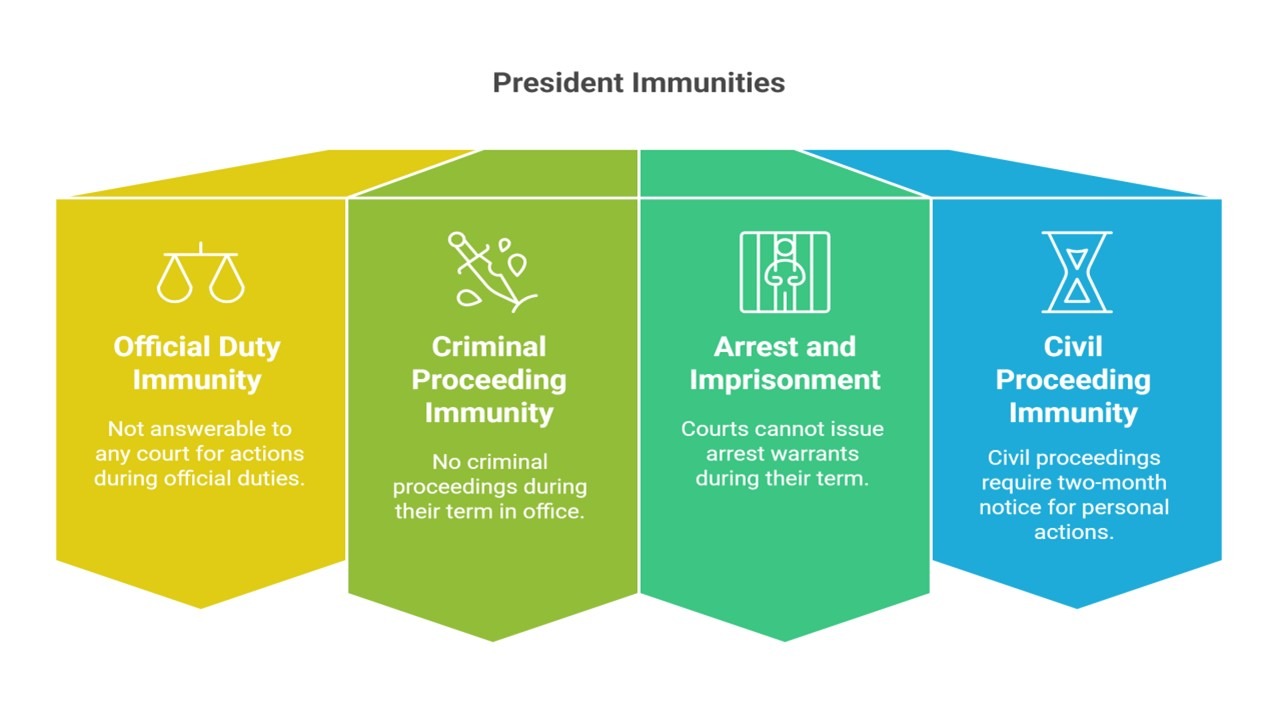

1. Immunities for the President and Governors (Article 361):

(i) The President and the Governors are not answerable to any court for actions taken during the exercise of their official duties.

(ii) No criminal proceedings can be initiated or continued against the President or Governor in any court during their term of office.

(iii) Courts cannot issue processes for the arrest or imprisonment of the President or Governor while they hold office.

(iv) No civil proceedings can be instituted against the President or the Governor in relation to actions taken in their personal capacity during their term, unless a two-month notice has been given.

2. Protection for Media Reporting (Article 361-A):

- This article states that no individual shall face civil or criminal action regarding the publication of a substantially true report of any proceedings of either House of Parliament or state legislature.

3. Parliamentary Privilege (Article 105):

- Members of Parliament cannot be held liable for any proceedings related to statements made or votes cast in Parliament or any of its committees.

4. State Legislature Privilege (Article 194):

- Similarly, members of the state legislature enjoy immunity from being held liable for statements made or votes cast in the legislature or its committees.

These exceptions illustrate that while equality before the law is a core principle, there are specific provisions in the Constitution that protect certain individuals and roles from legal accountability in order to maintain the functioning of government and legislative processes.

5. Article 31-C Exception:

- Article 31-C serves as an exception to Article 14 by stating that laws enacted by the state to enforce the Directive Principles outlined in clauses (b) and (c) of Article 39 cannot be challenged on the grounds that they violate Article 14. The Supreme Court has interpreted this to mean that “where Article 31-C applies, Article 14 does not.”

6. Immunity for Foreign Sovereigns:

- Foreign sovereigns, ambassadors, and diplomats enjoy immunity from both criminal and civil proceedings while serving in India.

7. Diplomatic Immunity:

- The United Nations Organization (UNO) and its agencies also possess diplomatic immunity, protecting them from legal actions in India.

2. Prohibition of Discrimination on Certain Grounds

- Article 15 of the Constitution prohibits the State from discriminating against any citizen based solely on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. The key terms in this article are “discrimination” and “only.”

- Discrimination is defined as making an unfavorable distinction or treating someone adversely compared to others.

- The term only indicates that discrimination on other grounds is not prohibited.

The second provision of Article 15 states that no citizen shall face any disability, liability, restriction, or condition based solely on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth regarding:

(a) Access to shops, public restaurants, hotels, and public entertainment venues, or

(b) Use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads, and other places of public resort maintained wholly or partly by state funds or dedicated to the use of the general public.

This provision prohibits discrimination not only by the State but also by private individuals, whereas the first provision restricts discrimination only by the State.

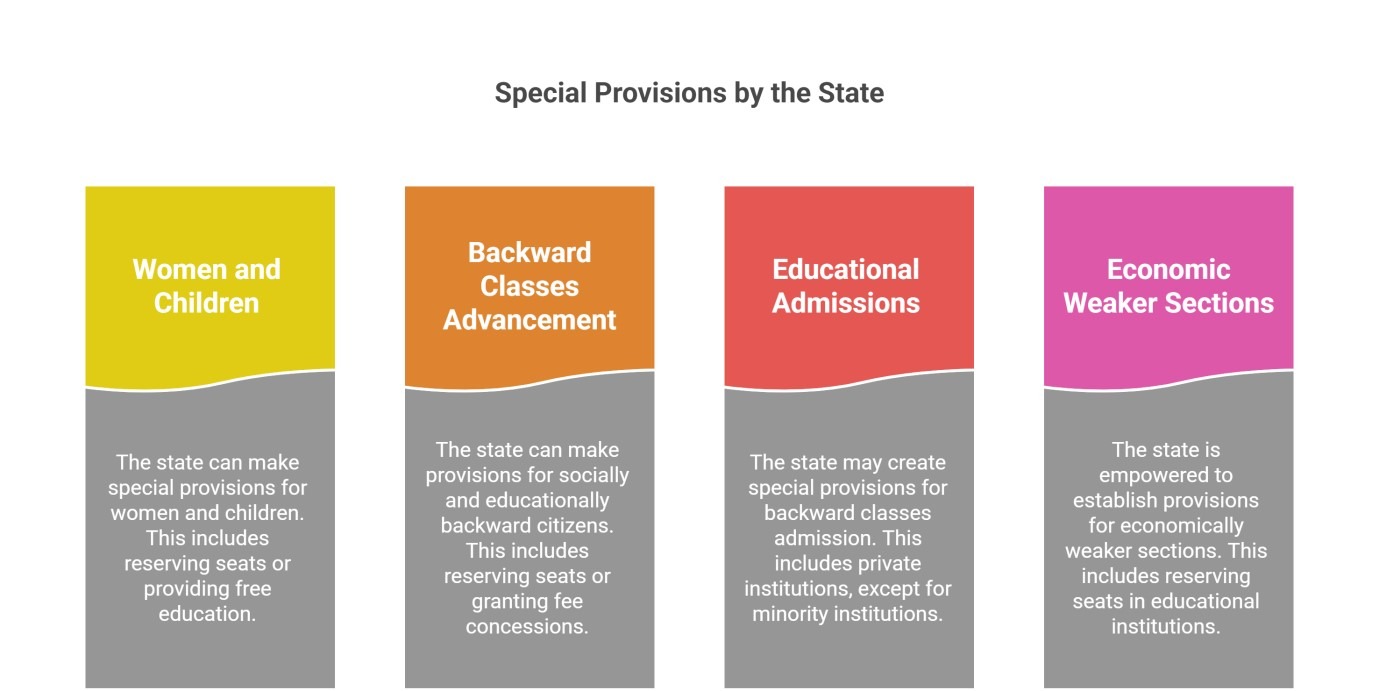

Exceptions to the General Rule of Non-Discrimination

There are specific exceptions to the rule of non-discrimination under Article 15, allowing the State to create special provisions:

- Special Provisions for Women and Children: The state is allowed to make provisions specifically for women and children, such as reserving seats for women in local bodies or providing free education for children.

- Advancement of Backward Classes: The state can make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward citizens, including Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). This may involve reserving seats or granting fee concessions in public educational institutions.

- Educational Admissions: The state may also create special provisions for the admission of socially and educationally backward classes, SCs, and STs in educational institutions, including private institutions, except for minority institutions.

- Economic Weaker Sections: The state is empowered to establish provisions for the advancement of economically weaker sections of society. This includes reserving up to 10% of seats for these sections in admissions to educational institutions, both public and private, excluding minority institutions. This reservation is additional to existing reservations and is determined based on family income and other indicators of economic disadvantage.

Overall, these exceptions to Article 15 highlight the Constitution’s aim to address inequalities and promote social justice within the framework of equality.

Reservation for OBCs in Educational Institutions

The provision for reservation for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in educational institutions was incorporated into the Constitution by the 93rd Amendment Act of 2005. To implement this provision, the Central Government enacted the Central Educational Institutions (Reservation in Admission) Act, 2006, which allocates a quota of 27% for OBC candidates in all central higher educational institutions, including the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs).

In April 2008, the Supreme Court upheld the validity of both the 93rd Amendment Act and the OBC Quota Act, while directing the Central Government to exclude the ‘creamy layer’ (the more advanced sections) among OBCs when enforcing the law.

The ‘creamy layer’ is defined to include the following categories of individuals, who will not benefit from the reservation:

- Constitutional Positions: Individuals holding constitutional posts, such as the President, Vice-President, Judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts, Chairman and Members of the UPSC and various State Public Service Commissions, Chief Election Commissioner, and Comptroller and Auditor General.

- Senior Government Officers: Group ‘A’ (Class I) and Group ‘B’ (Class II) officers in All India Services, Central and State Services, as well as employees in public sector undertakings (PSUs), banks, insurance companies, and similar positions in private employment.

- Military Officers: Persons with ranks of Colonel and above in the Army, as well as equivalent ranks in the Navy, Air Force, and paramilitary forces.

- Professionals: Professionals such as doctors, lawyers, engineers, artists, and consultants.

- Business Owners: Individuals engaged in trade, business, and industry.

- Land Owners: Families owning agricultural land above a certain limit, or possessing vacant land or buildings in urban areas.

- Income Criteria: Individuals whose families have a gross annual income exceeding ₹8 lakh will be excluded from the OBC quota. The “creamy layer” income ceiling has changed over the years: it was ₹1 lakh in 1993, increased to ₹5 lakh in 2004, ₹4.5 lakh in 2008, ₹6 lakh in 2013, and finally ₹8 lakh in 2017.

Reservation for EWSs in Educational Institutions

The 103rd Amendment Act of 2019 introduced a provision for the reservation of 10% for Economically Weaker Sections (EWSs) in educational institutions. This reservation applies to individuals who are not already covered under any existing reservation schemes for Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and OBCs. The eligibility criteria for EWS status are outlined as follows:

- Income Criteria: Individuals whose family’s gross annual income is below ₹8 lakh are classified as EWSs for the purpose of reservation. This income calculation includes all sources, such as salary, agriculture, business, and profession, and refers to the financial year prior to the application year.

- Asset Ownership: Individuals who own or possess any of the following assets are excluded from being identified as EWSs, regardless of family income:

- (a) 5 acres of agricultural land or more.

- (b) A residential flat measuring 1,000 sq. ft. or more.

- (c) A residential plot of 100 sq. yards or more in designated municipalities.

- (d) A residential plot of 200 sq. yards or more in areas outside of designated municipalities.

- Property Assessment: The property holdings of a family across different locations or cities will be aggregated when determining EWS status based on land or property ownership.

- Definition of Family: For these purposes, “family” includes the applicant, their parents, siblings under the age of 18, as well as their spouse and children below 18 years.

These provisions reflect India’s commitment to addressing economic disparities and ensuring that marginalized sections of society receive equitable access to education and opportunities.

3. Equality of Opportunity in Public Employment

Article 16 of the Indian Constitution guarantees equality of opportunity for all citizens regarding employment or appointment to any office under the State. It stipulates that no citizen should face discrimination or be declared ineligible for any position based solely on religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, or residence.

However, there are four exceptions to this general rule of equality of opportunity in public employment:

- Residence Requirement: Parliament has the authority to establish residence as a condition for certain jobs or appointments within a state, union territory, local authority, or other institutions. Although the Public Employment (Requirement as to Residence) Act of 1957 lapsed in 1974, such provisions remain applicable in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

- Reservation for Backward Classes: The State can reserve positions or appointments for any backward classes that are underrepresented in state services.

- Religious or Denominational Criteria: Laws may stipulate that holders of offices related to religious or denominational institutions or members of their governing bodies must belong to a specific religion or denomination.

- Reservation for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS): The State is authorized to reserve up to 10% of positions for economically weaker sections of citizens. This reservation is in addition to existing reservations and is defined by the State based on family income and other criteria indicating economic disadvantage.

These provisions ensure that while equality of opportunity is upheld, certain exceptions allow for the consideration of social and economic inequalities, promoting a more equitable workforce within the Indian public sector.

Mandal Commission and Aftermath

In 1979, the Morarji Desai Government established the Second Backward Classes Commission, chaired by B.P. Mandal, pursuant to Article 340 of the Indian Constitution. The commission’s mandate was to investigate the conditions of socially and educationally backward classes and recommend measures for their advancement. In 1980, the commission submitted its report, identifying 3,743 castes as socially and educationally backward, which constituted nearly 52% of the population, excluding Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

The Mandal Commission recommended a reservation of 27% of government jobs for Other Backward Classes (OBCs), which would increase the total reservation for SCs, STs, and OBCs to 50%. This recommendation was implemented a decade later, in 1990, when the V.P. Singh Government officially declared a 27% reservation in government jobs for OBCs.

In 1991, the Narasimha Rao Government introduced two significant changes:

(a) Preference would be given to the poorer sections within the OBC quota, thereby adopting economic criteria for granting reservations.

(b) An additional 10% reservation was allocated for economically backward sections of the higher castes not covered by any existing reservation schemes.

The landmark Mandal case (1992) saw the Supreme Court thoroughly examining the scope and extent of Article 16(4), which provides for job reservations for backward classes. The Court upheld the constitutional validity of the 27% reservation for OBCs but rejected the additional 10% reservation for economically backward higher castes. The Supreme Court placed several conditions on the OBC reservation:

- Exclusion of Creamy Layer: The advanced sections among the OBCs, referred to as the “creamy layer,” should not benefit from reservations.

- No Reservation in Promotions: Reservations should be limited to initial appointments only, with existing promotional reservations allowed for a maximum of five years (up to 1997).

- Reservation Ceiling: The total reserved quota for all categories should not exceed 50%, except in extraordinary circumstances, and this rule needs to be applied annually.

- Carry Forward Rule: The carry forward rule for unfilled vacancies (backlog) is valid but must not violate the 50% limit.

- Establishment of a Statutory Body: A permanent statutory body should be set up to address complaints regarding over-inclusion and under-inclusion in the list of OBCs.

The Mandal Commission and the subsequent developments played a pivotal role in shaping the policies regarding reservations for backward classes in India, influencing social dynamics and political discourse.Top of Form

Reservation for EWSs in Public Employment

The 103rd Amendment Act of 2019 introduced an exception that allows for a 10% reservation for Economically Weaker Sections (EWSs) in civil posts and services within the Government of India. This reservation is specifically for EWSs who are not already benefiting from existing reservation schemes for Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The eligibility criteria for this provision are detailed under Article 15.

There are specific scientific and technical posts that may be exempt from this reservation, provided they meet all the following criteria:

- The posts should be in grades higher than the lowest grade in Group A of the respective service.

- These posts must be classified as “scientific or technical” based on the Cabinet Secretariat Order of 1961. This classification applies to scientific and technical roles that require qualifications in natural sciences, exact sciences, applied sciences, or technology, where employees are expected to apply this knowledge in their duties.

- The positions should be related to conducting research or organizing, guiding, and directing research activities.

Abolition of Untouchability

- Article 17 of the Indian Constitution abolishes ‘untouchability’ and prohibits its practice in any form. Any enforcement of disability resulting from untouchability is considered an offense punishable by law. In 1976, the Untouchability (Offences) Act of 1955 was amended and renamed the Protection of Civil Rights Act of 1955 to expand its scope and strengthen its penalties. This Act defines ‘civil right’ as any right arising due to the abolition of untouchability by Article 17. Although the term ‘untouchability’ is not explicitly defined in the Constitution or the Act, the Mysore High Court clarified that Article 17 addresses the historical practice of untouchability, relating to social disabilities based on caste, rather than a literal or grammatical interpretation. The Supreme Court has also affirmed that rights under Article 17 apply against private individuals, and the State has a duty to uphold this right.

Abolition of Titles

- Article 18 abolishes titles and outlines four provisions:

- The State is prohibited from conferring any titles, except for military or academic distinctions, on anyone, whether a citizen or foreigner.

- Indian citizens are prohibited from accepting titles from any foreign state.

- Foreigners holding an office of profit or trust under the State cannot accept any title from a foreign state without the President’s consent.

- No citizen or foreigner holding an office of profit or trust under the State shall accept any presents, emoluments, or offices from or under any foreign state without the President’s consent.

- This means that hereditary titles of nobility, such as Maharaja, Raj Bahadur, and others conferred by colonial states, are banned under Article 18, as they contradict the principle of equal status for all.

- In 1996, the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutional validity of National Awards like the Bharat Ratna, Padma Vibhushan, Padma Bhushan, and Padma Shri. The Court ruled that these awards are not ‘titles’ as prohibited by Article 18, since they are not hereditary and do not conflict with the notion of equality, which recognizes merit. However, the Court stipulated that these awards should not be used as prefixes or suffixes, and failure to comply could result in forfeiture of the awards. These National Awards were first instituted in 1954, discontinued in 1977 by the Janata Party government, and revived in 1980 by the Indira Gandhi government.

Abolition of Untouchability

Article 17 of the Indian Constitution abolishes ‘untouchability’ and prohibits its practice in any form. Any enforcement of disability resulting from untouchability is considered an offense punishable by law. In 1976, the Untouchability (Offences) Act of 1955 was amended and renamed the Protection of Civil Rights Act of 1955 to expand its scope and strengthen its penalties. This Act defines ‘civil right’ as any right arising due to the abolition of untouchability by Article 17. Although the term ‘untouchability’ is not explicitly defined in the Constitution or the Act, the Mysore High Court clarified that Article 17 addresses the historical practice of untouchability, relating to social disabilities based on caste, rather than a literal or grammatical interpretation. The Supreme Court has also affirmed that rights under Article 17 apply against private individuals, and the State has a duty to uphold this right.

Abolition of Titles

- Article 18 abolishes titles and outlines four provisions:

- The State is prohibited from conferring any titles, except for military or academic distinctions, on anyone, whether a citizen or foreigner.

- Indian citizens are prohibited from accepting titles from any foreign state.

- Foreigners holding an office of profit or trust under the State cannot accept any title from a foreign state without the President’s consent.

- No citizen or foreigner holding an office of profit or trust under the State shall accept any presents, emoluments, or offices from or under any foreign state without the President’s consent.

- This means that hereditary titles of nobility, such as Maharaja, Raj Bahadur, and others conferred by colonial states, are banned under Article 18, as they contradict the principle of equal status for all.

- In 1996, the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutional validity of National Awards like the Bharat Ratna, Padma Vibhushan, Padma Bhushan, and Padma Shri. The Court ruled that these awards are not ‘titles’ as prohibited by Article 18, since they are not hereditary and do not conflict with the notion of equality, which recognizes merit. However, the Court stipulated that these awards should not be used as prefixes or suffixes, and failure to comply could result in forfeiture of the awards. These National Awards were first instituted in 1954, discontinued in 1977 by the Janata Party government, and revived in 1980 by the Indira Gandhi government.

Right to Freedom

1. Protection of Six Rights

Article 19 of the Indian Constitution ensures six fundamental rights for all citizens:

- Right to freedom of speech and expression.

- Right to assemble peacefully and without arms.

- Right to form associations, unions, or cooperative societies.

- Right to move freely within the territory of India.

- Right to reside and settle in any part of India.

- Right to practice any profession or carry out any occupation, trade, or business.

Initially, Article 19 included a seventh right—the right to acquire, hold, and dispose of property—but this was removed by the 44th Amendment Act in 1978.

These rights are protected against actions by the state, not private individuals. They apply exclusively to citizens and to shareholders of companies, but not to foreigners or legal entities like companies and corporations. The State may impose ‘reasonable’ restrictions on these rights only for reasons specified within Article 19 itself.

Freedom of Speech and Expression

This right allows every citizen to express their views, opinions, beliefs, and convictions freely using words, writing, printing, imaging, or in any other way. The Supreme Court has clarified that this freedom includes:

- The right to propagate one’s views and the views of others.

- Freedom of the press.

- Freedom for commercial advertisements.

- Protection against phone tapping.

- The right to broadcast, indicating that the government does not have a monopoly over electronic media.

- Protection against bandhs called by political parties or organizations.

- The right to information about government activities.

- Freedom of silence.

- The right against pre-censorship of a newspaper.

- The right to demonstrate or picket, although it does not include the right to strike.

The State may impose reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the freedom of speech and expression for specific reasons, which include:

- Sovereignty and integrity of India

- Security of the state

- Friendly relations with foreign states

- Public order

- Decency or morality

- Contempt of court

- Defamation

- Incitement to an offence

These grounds help balance individual freedoms with the need to maintain order and protect the interests of the state and society.

Freedom of Assembly

Every citizen has the right to assemble peacefully and without arms, which encompasses the right to hold public meetings, demonstrations, and processions. This freedom may only be exercised on public land and must be conducted peacefully and without weapons. The provision does not extend to violent, disorderly, or riotous assemblies, or those that cause a breach of public peace or involve arms. Importantly, this right does not include the right to strike.

The State can impose reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right to assembly for two primary reasons: the sovereignty and integrity of India and the maintenance of public order, including traffic management in the area.

Under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code (1973), a magistrate can prohibit an assembly, meeting, or procession if there is a risk of obstruction, annoyance, danger to human life, health or safety, public disturbance, or riot. Additionally, according to Section 141 of the Indian Penal Code, an assembly of five or more persons is deemed unlawful if its objective is to:

(a) Resist the execution of any law or legal process,

(b) Forcibly occupy someone else’s property,

(c) Commit mischief or criminal trespass,

(d) Coerce someone into committing an illegal act, or

(e) Threaten the government or its officials while exercising lawful powers.

Freedom of Association

All citizens have the right to form associations, unions, or cooperative societies. This encompasses the formation of political parties, companies, partnership firms, societies, clubs, organizations, trade unions, or any collective group. It includes not only the right to create an association or union but also the right to continue being part of one, as well as the negative right to choose not to associate with any group.

The State may impose reasonable restrictions on this right based on grounds of sovereignty and integrity of India, public order, and morality. Within these limitations, citizens enjoy the freedom to form associations for lawful purposes and objectives. However, the right to obtain official recognition of an association is not considered a fundamental right.

The Supreme Court has clarified that trade unions do not have an inherent right to effective bargaining, the right to strike, or the right to declare a lockout. The right to strike can be regulated by appropriate industrial laws.

Freedom of Movement

This freedom grants every citizen the right to move freely throughout the territory of India. Citizens can travel from one state to another or within a state, emphasizing that India functions as a unified entity for its citizens. The objective of this right is to foster a sense of national identity while discouraging regionalism.

Reasonable restrictions on this freedom can be imposed based on two grounds: the interests of the general public and the protection of the interests of scheduled tribes. Entry into tribal areas may be limited to preserve the unique culture, language, customs, and traditions of these tribes, as well as to protect their traditional livelihoods and properties from exploitation.

The Supreme Court has established that the freedom of movement for prostitutes may be restricted on grounds of public health and morality. Additionally, the Bombay High Court upheld restrictions on the movement of individuals affected by AIDS.

The freedom of movement encompasses two dimensions: internal movement (the right to travel within the country) and external movement (the right to leave the country and return). Article 19 specifically protects the internal movement, while the external dimension is addressed under Article 21, which encompasses the right to life and personal liberty.

Freedom of Residence

Every citizen has the right to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India. This right consists of two components: (a) the right to reside anywhere in the country, allowing for temporary stays at any location, and (b) the right to settle in any part of the country, which involves establishing a home or permanent domicile.

The purpose of this right is to eliminate internal barriers within the country and foster a sense of unity and nationalism, thereby discouraging narrow-mindedness.

The State may impose reasonable restrictions on this right based on two grounds: the interests of the general public and the protection of the interests of scheduled tribes. Restrictions may be placed on outsiders’ ability to reside and settle in tribal areas to safeguard the unique culture, language, customs, and traditions of these tribes, as well as to protect their traditional livelihoods and properties from exploitation. In several regions, tribal communities are allowed to manage their property rights according to their customary laws and practices.

The Supreme Court has ruled that certain areas may be restricted for specific individuals, such as prostitutes and habitual offenders.

It’s important to note that the right to residence and the right to movement overlap to some degree; both rights are complementary to one another.

Freedom of Profession, etc.

All citizens have the right to practice any profession or engage in any occupation, trade, or business. This right is comprehensive as it encompasses various means of earning a livelihood.

The State can impose reasonable restrictions on this right in the interest of the general public. Additionally, the State has the authority to:

(a) Set professional or technical qualifications required for practicing any profession or carrying out any occupation, trade, or business.

(b) Undertake any trade, business, industry, or service, either exclusively (completely or partially) or in competition with citizens.

Consequently, there is no basis for objection when the State operates a trade, business, industry, or service either as a monopoly or in competition with individual citizens. The State is not obligated to justify its monopoly.

However, this right does not extend to engaging in professions, businesses, trades, or occupations that are considered immoral (such as trafficking in women or children) or dangerous (such as dealing in harmful drugs or explosives). The State has the authority to completely prohibit these activities or regulate them through licensing.

Protection in Respect of Conviction for Offences

Article 20 of the Indian Constitution provides protections against arbitrary and excessive punishment for individuals, whether they are citizens, foreigners, or legal entities like companies or corporations. This article includes three key provisions:

(a) No Ex-Post-Facto Law: No individual shall be convicted of any offense except for violating a law that was in effect at the time the act was committed, nor shall they be subjected to a penalty greater than what was prescribed by that law at that time. An ex-post-facto law imposes retroactive penalties on acts already committed or increases penalties for such acts. This prohibition applies specifically to criminal laws and does not extend to civil or tax laws, meaning civil liabilities or taxes can be applied retroactively. However, this provision protects against conviction or sentencing under an ex-post-facto criminal law but does not prevent a trial based on such laws. Furthermore, this protection does not apply in cases of preventive detention or when demanding security from an individual.

(b) No Double Jeopardy: No person shall be prosecuted or punished more than once for the same offense. This protection is applicable only in court or judicial tribunal proceedings, and does not apply to trials before departmental or administrative bodies, as they are not judicial in nature.

(c) No Self-Incrimination: No person accused of an offense shall be forced to be a witness against themselves. This protection encompasses both oral and documentary evidence. However, it does not extend to (i) the compulsory production of material objects, (ii) the requirement to provide thumb impressions, specimen signatures, or blood samples, and (iii) the mandatory exhibition of the body. Additionally, this protection is limited to criminal proceedings and does not apply to civil cases or non-criminal proceedings.

Protection of Life and Personal Liberty

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution states that no person shall be deprived of their life or personal liberty except according to a procedure established by law. This right is available to both citizens and non-citizens.

In the landmark Gopalan case (1950), the Supreme Court interpreted Article 21 narrowly, holding that its protection applied only against arbitrary executive action, allowing deprivation of life and personal liberty through established laws. This interpretation was based on the phrase “procedure established by law,” which differs from the “due process of law” found in the American Constitution. Consequently, laws outlining procedures could not be contested on grounds of being unreasonable, unfair, or unjust. The Court also defined “personal liberty” as relating only to the individual’s physical body.

However, in the Menaka case (1978), the Supreme Court reexamined its stance, adopting a broader interpretation of Article 21. The Court ruled that the right to life and personal liberty can be curtailed by law, provided that the prescribed procedure is reasonable, fair, and just. This introduced the concept of “due process of law” into Indian jurisprudence, expanding protections against both arbitrary executive and legislative actions. Furthermore, the Court determined that the “right to life” includes the right to live with dignity, encompassing all facets that contribute to a meaningful and complete life. The term “personal liberty” was found to be extensive, covering various rights integral to individual freedoms.

The Supreme Court has since reaffirmed its ruling in the Menaka case in subsequent judgments and has identified several rights as part of Article 21, including:

- Right to live with human dignity.

- Right to a decent environment, including pollution-free water and air, and protection against hazardous industries.

- Right to livelihood.

- Right to privacy.

- Right to shelter.

- Right to health.

- Right to free education up to 14 years of age.

- Right to free legal aid.

- Right against solitary confinement.

- Right to a speedy trial.

- Right against handcuffing.

- Right against inhuman treatment.

- Right against delayed execution.

- Right to travel abroad.

- Right against bonded labor.

- Right against custodial harassment.

- Right to emergency medical aid.

- Right to timely medical treatment in government hospitals.

- Right not to be evicted from a state.

- Right to a fair trial.

- Right of prisoners to access necessities of life.

- Right of women to be treated with decency and dignity.

- Right against public hanging.

- Right to roads in hilly areas.

- Right to information.

- Right to reputation.

- Right to appeal from a judgment of conviction.

- Right to family pension.

- Right to social and economic justice and empowerment.

- Right against bar fetters.

- Right to an appropriate life insurance policy.

- Right to sleep.

- Right to freedom from noise pollution.

- Right to sustainable development.

- Right to opportunities.

These rights contribute significantly to ensuring respect for life and personal liberty, reinforcing the fundamental ethos of human dignity and socio-economic justice in India.

Article 21: Protection of Life and personal liberty

- No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.

- It is available to both citizens and foreigners.

- Maneka Gandhi case, 1978: Taking wider interpretation of Article 21 – Apex court ruled that the right to life & personal

liberty of a person can be deprived by a law provided the procedure prescribed by law is reasonable, fair and just.

SC introduced an American expression of “Due process of law”

Parameter | Procedure Established by Law | Due Process of Law |

Origin | British Constitution | United States Constitution |

Scope | Does not assess whether laws are fair, just, or non-arbitrary; only checks if the procedure is followed. | Examines both the procedural and substantive aspects to ensure the law is fair, just, and non-arbitrary. |

Role of Judiciary | Judiciary evaluates only the procedure used to enact the law. | Judiciary assesses both the procedure and the fairness of the law’s content. |

Protection | Protects citizens’ rights against arbitrary actions of the executive. | Protects citizens’ rights against arbitrary actions of both the executive and the legislature. |

Constitutional Provision | Explicitly provided under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. | Not explicitly mentioned in the Indian Constitution, but interpreted and enforced through judicial activism. |

Right to be forgotten

- Context: SC recently examined an acquitted man’s ‘right to be forgotten’.

- The “Right to be Forgotten” is the right to remove or erase content so that it’s not accessible to the public at large.

- Deletion of information in the form of news, video, or photographs deleted from internet records.

- It falls under the purview of an individual’s right to privacy, which is governed by the Personal Data Protection Act, 2023.

- Right to Privacy a FR under Article 21 (Puttaswamy case)

- The right to be forgotten is distinct from the right to privacy as the latter constitutes information that is not publicly known, whereas the former involves removing information that was publicly known at a certain time.

Right to reside

- Context:The Delhi High Court clarified that foreigners do not have a constitutional right to reside in India while hearing a habeas corpus petition concerning the detention of a suspected Bangladeshi national by the Foreign Regional Registration Office.

- Article 21: Foreigners in India are entitled only to the Fundamental Right to Life and Liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution.

Legal Rights of foreigners:

- Regulation of Foreigners: the Registration of Foreigners Act (1939) and the Foreigners Act (1946) govern foreigners’ entry, stay, and departure, granting the central government powers to protect foreigners’ fundamental rights.

- Section 3, Foreigners Act (1946): Empowers the government to impose movement restrictions, specify residence, prohibit certain associations, and enforce house arrest, imprisonment, solitary confinement, or summary expulsion.

- Passport Act (1920) and Foreigners Act (1946): Permit the expulsion or deportation of foreigners from India.

Right to adopt

- Context: the Delhi High Court ruled that the right to adopt a child is not a fundamental right under the Indian Constitution.

Delhi High Court Ruling

- Regulation 5(7): Couples with two or more biological children can only adopt special needs or hard-to-place children.

- Special Needs & Hard-to-Place: Defined under Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act and by adoption procedure status.

- Regulation 5(2) Conditions:

- Married couples need mutual consent.

- Single females can adopt any gender; single males can’t adopt girls.

- Regulation 5(7): Couples with two or more biological children can only adopt special needs or hard-to-place children.

Laws governing the adoption of orphaned, abandoned, and surrendered children

- Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015: the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA), under the Ministry ofWomen & Child Development, serves as the primary regulatory body for in-country and international adoptions of Indian children.

- HAMA for Hindus: Separate adoption law for Hindu community.

Right against adverse effects of climate change

- Context: the Supreme Court has expanded the scope of Articles 14 and 21 to include the “right against the adverse effects of climate change”.

- Great Indian Bustard Conservation: the Supreme Court heard a plea to protect the GIB’s habitat from power lines, with an April 2021 order limiting overhead transmission lines in specific Rajasthan areas for GIB conservation.

Constitutional Provisions:

- Article 21: Recognizes the right to life and personal liberty, encompassing environmental protection.

- Article 14: Ensures equality before the law, supporting the right to a clean environment as part of equal protection.

- Climate Change Legislation: India lacks a unified law targeting climate change.Bottom of Form

Article 21 A: Right to Education

- Provision Free and compulsory education to children in the age of 6 to 14 years

86th CAA. 2002 – Inserted Article 21 A

- Made changes in DPSP: Article 45 – Early childhood care and education for all children until they complete the age of 6 years’.

- Added a new Fundamental duty: Opportunities for education to his child or ward between the age of 6 and 14 years’ Enforcement Right to Education 2009 was enacted to enforce this.

Article 22: Protection against arrest and detention

- Grants protection to persons under both preventive and punitive detention.

- Punitive detention: Punishment for an offence committed after trial + conviction in court.

- Preventive detention: Without trial + conviction in court.

Bail

- Context: the Supreme Court has said that the right to default bail is a fundamental right of an accused if the investigating agency failedto complete the probe and file charge sheet within a stipulated time-period.

Categories of bail:

- Bailable Offences: Bailable offences are those for which the accused person has a right to be released on bail.

Eg: minor traffic violations, simple assault, and certain types of property offences.

- The BNSS empowers magistrates to grant bail for bailable offences as a matter of right.

- It involves the release of furnishing a bail bond, without or without security.

Non-bailable Offences:

- Non-bailable offences are those for which the accused person is not entitled to be released on bail as a matter of right.

- Instead, the accused person must apply to the court for bail and convince the court that they deserve to be released pending trial.

- These offences are cognizable, which enables the police officer to arrest without a warrant.

- In such cases, a magistrate would determine if the accused is fit to be released on bail.

- Some examples of non-bailable offenses in India include murder, rape, kidnapping, and certain types of economic offenses.

Types of Bail

- Regular bail: An individual who has been arrested or is in police custody is usually granted a regular bail.

- Interim bail: It is a temporary measure that is valid during an ongoing application or when the court is hearing an application for anticipatory or regular bail.

- Anticipatory bail: It is given to an individual who is in anticipation of getting arrested for a non-bailable offence by the police.

Detention

- Context: Recently, the Supreme Court observed that preventive detention laws in India are a colonial legacy and confer arbitrary power to the state.

About preventive detention

- A detainee under preventive detention has no right of personal liberty guaranteed by Article 19 or Article 21.

- 44th Constitutional Amendment Act: the amendment reduced the period of detention without obtaining the opinion from the advisory board from three to two months, however, this provision is yet not implemented yet.

- The Constitution of India gives the Parliament the authority to enact rules governing preventive detention where they are necessary for national security, foreign policy, or defence. However, both Parliament and State Legislature have powers to enact such laws for the reasons related to the maintenance of public order.

UAPA

- Context: the Supreme Court ruled that NewsClick founder Prabir Purkayastha’s arrest under the UAPA violated due process, underscoring the necessity of transparency and adherence to constitutional rights in arrests.

Why was the arrest invalidated by the Supreme Court?

- Article 22(1) and Right to Information: the Court highlighted that under Article 22(1), an accused has a fundamental right to be informed in writing of the reasons for their arrest, and any violation of this right nullifies the arrest.

- Clarification on FIR’s Role: FIR serves only to initiate investigation and is not a comprehensive document.

- Protection in case of arrest –Informed about ground of arrest

- Consult and defend by legal practitioner

- Produced before the magistrate within 24 hours.

*Not available to enemy aliens or under preventive detention.

Protection in case of Preventive detention

- Detention period cannot exceed 3 months

– Beyond 3 months report of advisory board needed

– Board to consist Judges of High court

- Ground of detention to be communicated to the detenu (no need to tell facts related to public interest)

- Opportunity to make representation against a detention order.

- Parliament has power to Increase 3 month detention period without obtaining advisory board opinion.

RIGHTS AGAINST EXPLOITATION (ARTICLE 23 – 24)

Article 23: Protection against Human Trafficking and Forced Labour

- Article 23 of the Indian Constitution provides a vital safeguard against exploitation by prohibiting traffic in human beings, begar (forced labour without payment), and other similar forms of forced labour. It stands as a fundamental right available not only against the actions of the State but also against private individuals, ensuring broader protection for all citizens.

Key Features:

- Wider Applicability: Article 23 imposes a blanket prohibition, meaning that both the government and private citizens are prohibited from engaging in practices like human trafficking, begar, and forced labour.

- Exception for Public Purposes: The State is permitted to impose compulsory service for public purposes. However, such service must not discriminate on the basis of religion, race, caste, or class.

Examples:

- Military conscription during wartime.

- Mandatory participation in community service or disaster relief efforts.

- Understanding Begar: Begar refers to a system where a person is forced to work without any payment. This form of exploitation was historically widespread under feudal and colonial systems and is explicitly outlawed under Article 23.

- Understanding Forced Labour: Forced labour involves compelling an individual to work against their will through the use of force, coercion, or undue pressure. This can include situations where a person is made to work to repay a debt under unfair conditions (bonded labour), which is also illegal.

Significance:

Article 23 upholds the dignity of individuals and reinforces the right to freedom and equality enshrined in the Constitution. It empowers the State to legislate against trafficking and forced labour, leading to landmark laws such as:

- The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976

- The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956

Article 24: Prohibition of Employment of Children in Factories, Mines, and Hazardous Occupations

- Article 24 of the Indian Constitution plays a crucial role in safeguarding the rights and well-being of children. It categorically prohibits the employment of children below the age of 14 years in factories, mines, and any other hazardous occupations that could endanger their health, safety, or moral development.

Key Features:

- Absolute Prohibition in Hazardous Work: No child under the age of 14 can be employed or permitted to work in environments that pose significant physical or mental risks, such as heavy industries, construction sites, chemical factories, or underground mining operations.

- Exception for Non-Hazardous Work: Article 24 does not completely bar children from working. It allows their involvement in non-hazardous and harmless activities, such as assisting in family enterprises or working in fields traditionally considered safe, provided such work does not interfere with their education and development.

Associated Laws and Measures:

- The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 regulates the conditions of employment of children and prohibits their engagement in specific occupations and processes deemed hazardous.

- The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2016 further strengthened the law by:

- Completely prohibiting the employment of children below 14 years in all occupations and processes, except for helping in family enterprises or the entertainment industry (under strict conditions).

- Prohibiting the employment of adolescents (aged 14–18 years) in hazardous occupations and processes.

Significance:

- Protects children from exploitation, abuse, and hazardous working conditions.

- Reinforces the fundamental right to education under Article 21A by ensuring that children are not forced into labour instead of attending school.

- Contributes to India’s commitment to international conventions like the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the International Labour Organization (ILO) Conventions.

Right to Freedom of Religion (Article 25 to 28)

- These provisions of the Indian Constitution guarantee individuals the freedom to profess, practice, and propagate the religion of their choice. It ensures secularism by mandating that the state maintain neutrality and treat all religions equally.

Freedom of Conscience and Free Profession, Practice, and Propagation of Religion (Article 25)

- This article says that all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion. The implications of these are:

Freedom of conscience

- Individuals have the freedom to shape their relationship with God and other creatures in whatever way they desire.

Right to Profess

- To declare one’s religious beliefs and faith openly and freely.

Right to Practice

- To perform religious worship, rituals, ceremonies, and exhibition of beliefs and ideas.

Right to Propagate

- To transmit or disseminate one’s religious beliefs to others. However, it does not include a right to convert another person to one’s religion.

Freedom to Manage Religious Affairs (Article 26)

- This provision states that every religious denomination or its section shall have the following rights-

- Right to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes,

- Right to manage its affairs in matters of religion,

- Right to own and acquire movable and immovable property, and

- Right to administer such property as per law.

- This provision states that every religious denomination or its section shall have the following rights-

Freedom from Taxation for Promotion of a Religion (Article 27)

- This provision prohibits the State from levying taxes for promoting or maintaining any particular religion or religious denomination. It upholds the principle of secularism and ensures that the State remains neutral in matters of religion, fostering equality and religious freedom for all citizens.

Freedom from Attending Religious Instruction (Article 28)

It makes provisions for religious instruction in different categories of educational institutions, as described below:

- Institutions wholly maintained by the State- religious instruction is completely prohibited.

- Institutions administered by the State but established under any endowment or trust – religious instruction is permitted.

- Institutions recognized by the State- religious instruction is permitted on a voluntary basis i.e. with the consent of the person.

- Institutions receiving aid from the State- religious instruction is permitted on a voluntary basis i.e. with the consent of the person.

Cultural and Educational Rights (Article 29 to Article 30)

- These provisions of the Indian Constitution safeguard the rights of minorities to conserve their culture, language, and script.

Protection of Interests of Minorities (Article 29)

It provides that:

- Any section of citizens having a distinct language, script, or culture of its own, shall have the right to conserve the same.

- No citizen shall be denied admission into any educational institution maintained by the state or receiving aid out-of-state funds on grounds only of religion, race, caste, or language.

As noted by the Supreme Court, the use of the phrase ‘section of citizens’ in the Article means that it applies to minorities as well as the majority. Thus, the scope of this article is not necessarily restricted to minorities only.

Right of Minorities to Establish and Administer Educational Institutions (Article 30)

- This provision grants minorities (both religious as well as linguistic) certain rights, such as the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice, the right to impart education to their children in its own language, etc.

It is to be noted that the protection under this provision is confined only to minorities (religious or linguistic) and does not extend to any section of citizens (as under Article 29).

Right to Constitutional Remedies (Article 32)

It confers the right to remedies for the enforcement of the fundamental rights in case of violation of the same. It makes the following provisions regarding the same:

- The right to move the Supreme Court for the enforcement of the Fundamental Rights is guaranteed.

- The Supreme Court shall have the power to issue directions, orders, or writs

- for the enforcement of fundamental rights.

- The Parliament can empower any other court to issue directions, orders, or writs for the enforcement of fundamental rights.

- The right to move the Supreme Court shall not be suspended except as otherwise provided for by the Constitution.

- These provisions give the right to get the Fundamental Rights protected, making the Fundamental Rights real.

Armed Forces (Article 33)

- This provision empowers Parliament to enact laws that restrict or modify the application of certain fundamental rights for members of the armed forces, police forces, intelligence agencies, or similar forces tasked with the maintenance of public order.

- The objective of this provision is to ensure the proper discharge of their duties in the interest of national security and the maintenance of discipline among them.

Martial Law (Article 34)

- This provision provides for restrictions on fundamental rights during the operation of martial law in any area within the territory of India.

- However, the expression ‘martial law’ has not been defined anywhere in the Constitution.

Directive Principles of State Policy

The Directive Principles of State Policy are outlined in Part IV of the Indian Constitution, specifically from Articles 36 to 51. The framers of the Constitution drew inspiration for these principles from the Irish Constitution of 1937, which itself had adapted them from the Spanish Constitution. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar referred to these principles as “novel features” of the Indian Constitution, highlighting their significance. Together with Fundamental Rights, the Directive Principles embody the philosophy of the Constitution and are considered its soul. Granville Austin has described these principles and Fundamental Rights as the “Conscience of the Constitution.”

Features of the Directive Principles

1. Purpose and Meaning:

The term “Directive Principles of State Policy” signifies the ideals that the State should consider when formulating policies and enacting laws. They serve as constitutional directives or recommendations for the State in legislative, executive, and administrative matters. According to Article 36, the term “State” in Part IV has the same meaning as in Part III, which encompasses the legislative and executive branches of the central and state governments, as well as all local authorities and public authorities in the country.

2. Comparison to Previous Instruments:

The Directive Principles are similar to the “Instrument of Instructions” outlined in the Government of India Act of 1935. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar likened the Directive Principles to these instruments that provided guidance to the Governor-General and provincial governors under British rule. The key distinction is that the Directive Principles serve as instructions directed at the legislature and executive.

3. Comprehensive Program:

The Directive Principles provide a thorough economic, social, and political framework for a modern democratic state. Their objectives align with the high ideals of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity as expressed in the Preamble of the Constitution. They promote the vision of a “welfare state,” in contrast to the “police state” that existed under colonial rule, aiming to foster economic and social democracy in India.

4. Non-justiciability:

These principles are non-justiciable, meaning they are not legally enforceable by the courts. Consequently, governments (central, state, and local) cannot be compelled to implement them. Nevertheless, Article 37 of the Constitution asserts that these principles are fundamental to the governance of the country and states that it is the duty of the State to apply them when creating laws.

5. Judicial Relevance:

Although Directive Principles are non-justiciable, they assist the courts in analyzing and determining the constitutional validity of laws. The Supreme Court has ruled that if a law seeks to implement a Directive Principle, it may be deemed “reasonable” in relation to Article 14 (equality before law) or Article 19 (freedoms), thus protecting the law from being declared unconstitutional.

These features underscore the importance of Directive Principles as guiding standards for policy-making and governance, while also reflecting the broader objectives of justice, equality, and democracy within the Indian constitutional framework.

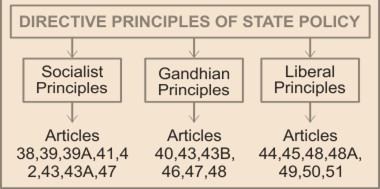

Classification of the Directive Principles

While the Indian Constitution does not formally classify the Directive Principles of State Policy, they can be categorized into three broad groups based on their content and objectives: socialistic, Gandhian, and liberal-intellectual.

1. Socialistic Principles

These principles are rooted in the ideology of socialism and lay out the framework for a democratic socialist state aimed at achieving social and economic justice while working towards a welfare state. They direct the state to:

- Promote the welfare of the people by ensuring a social order infused with justice—social, economic, and political—and to minimize inequalities in income, status, facilities, and opportunities (Article 38).

- Secure:

(a) The right to adequate means of livelihood for all citizens.

(b) Equitable distribution of community resources for the common good.

(c) Prevention of wealth concentration and control over production.

(d) Equal pay for equal work regardless of gender.

(e) Protection of the health and well-being of workers and children from exploitation.

(f) Opportunities for healthy development for children (Article 39).

3. Promote equal justice and ensure free legal aid for the poor (Article 39A).

4. Secure the right to work, education, and public assistance in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness, and disability (Article 41).

5. Provide just and humane working conditions and maternity relief (Article 42).

6. Ensure a living wage, a decent standard of living, and social and cultural opportunities for all workers (Article 43).

7. Facilitate workers’ participation in industry management (Article 43A).

8. Enhance nutrition levels and improve public health (Article 47).

2. Gandhian Principles

These principles reflect Gandhian philosophy and embody the vision for societal reconstruction that Gandhi articulated during India’s national movement. They require the State to:

- Organize village panchayats and empower them to function as units of self-governance (Article 40).

- Encourage cottage industries on an individual or cooperative basis in rural areas (Article 43).

- Foster the voluntary creation, autonomy, democratic governance, and professional management of cooperative societies (Article 43B).

- Advance the educational and economic interests of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and other marginalized groups, while protecting them from social injustice and exploitation (Article 46).

- Prohibit the consumption of intoxicating substances that are harmful to health (Article 47).

- Prevent the slaughter of cows, calves, and other milch and draft animals, along with efforts to improve their breeds (Article 48).

3. Liberal-Intellectual Principles

This category embodies the principles of liberalism, directing the state to:

- Ensure a uniform civil code for all citizens across the country (Article 44).

- Provide early childhood care and education for all children until the age of six (Article 45).

- Organize agriculture and animal husbandry using modern scientific methods (Article 48).

- Safeguard the environment, including the protection of forests and wildlife (Article 48A).

- Protect monuments and sites of artistic or historic significance, declared of national importance (Article 49).

- Separate the judiciary from the executive within state public services (Article 50).

- Promote international peace and security, maintain just relations among nations, respect international law and treaty obligations, and encourage the resolution of international disputes through arbitration (Article 51).

These classifications illuminate the diverse objectives embedded within the Directive Principles, which collectively aim to foster a just and equitable society in India.

New Directive Principles

The 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 introduced four new Directive Principles to the Indian Constitution, emphasizing the role of the State in achieving various social and economic goals. These principles require the State to:

- Secure Opportunities for Healthy Development of Children: This is outlined in Article 39, focusing on the well-being and development of children.

- Promote Equal Justice and Free Legal Aid: Article 39A mandates that the State ensure equal justice and provide free legal assistance to the underprivileged.