Federal System

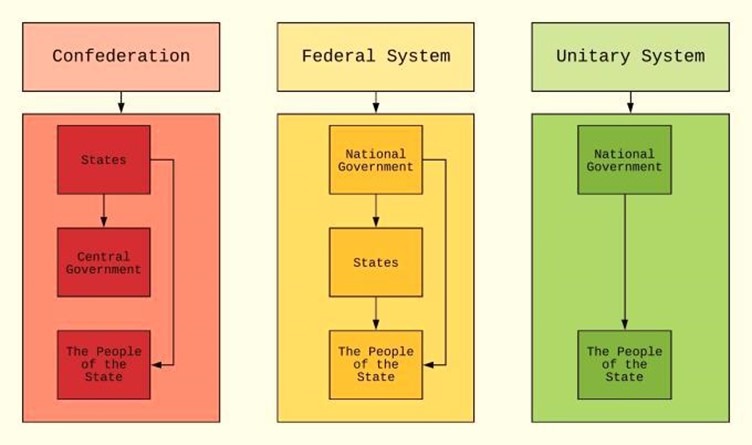

Political scientists distinguish between unitary and federal systems of government based on the relationship between national and regional governments.

Unitary Government:

- In this system, all governmental powers are centralized in the national government. Regional governments, if they exist, derive their authority directly from the national government. Examples include countries like Britain, France, Japan, China, Italy, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, and Spain.

Federal Government:

- Here, powers are constitutionally divided between national and regional governments, allowing both to operate independently within their respective jurisdictions. Examples of countries with a federal system are the United States, Switzerland, Australia, Canada, Russia, Brazil, and Argentina. In a federal model, the national level is referred to as the Federal, Central, or Union government, whereas the regional level is known as the state or provincial government.

The term ‘federation’ derives from the Latin word “foedus,” meaning “treaty” or “agreement.” Thus, a federation is a new political system formed through an agreement among various units. These units can be referred to as states (in the US), cantons (in Switzerland), provinces (in Canada), or republics (in Russia).

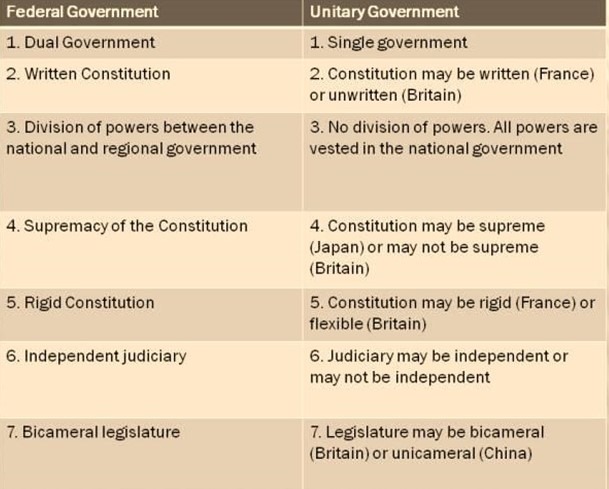

Here is a comparative overview of the features of federal and unitary governments:

This comparison highlights the key structural differences in the organization and distribution of powers within federal and unitary systems.

A federation can emerge through integration, where several smaller, weaker, or economically disadvantaged independent states unite to form a more robust and powerful entity, as exemplified by the United States. Conversely, disintegration involves transforming a sizable unitary state into a federation by granting autonomy to its provinces, as seen in Canada.

The United States, the first and oldest federation globally, was established in 1787 after the American Revolution, originally comprising 13 states and now including 50. It is often regarded as a federation model. The Canadian Federation, initially formed with four provinces in 1867 and now consisting of ten, is also a venerable federation.

India’s Constitution institutes a federal government system, chosen by the framers for the country’s vast size and socio-cultural diversity. They believed federalism not only ensures effective governance but also balances national unity with regional autonomy.

The Indian Constitution does not use the term “federation.” Instead, Article 1 describes India as a “Union of States.” Dr. B.R. Ambedkar explained this preference for two reasons: (i) the Indian federation did not arise from an agreement among states, unlike the American federation, and (ii) states lack the right to secede, making the federation an indestructible union.

India’s federal system mirrors the “Canadian model,” emphasizing a robust central government, unlike the “American model.” The Indian federation shares similarities with the Canadian model in its formation via disintegration, preference for the term “Union,” and its centralizing tendency, which allocates more power to the centre compared to the states.

Federal Features of the Constitution of India

The Indian Constitution encompasses a range of federal features, which are detailed below:

1. Dual Polity:

- The Constitution establishes a dual system of governance, consisting of the Union at the national level and states on the periphery. Each entity holds sovereign powers that they exercise within the areas designated to them by the Constitution. The Union government manages national matters such as defense, foreign relations, currency, and communication. In contrast, state governments oversee regional and local issues, including public order, agriculture, health services, and local governance.

2. Written Constitution:

- The Constitution is not only a written document but also the longest in the world. Initially, it included a Preamble, 395 Articles arranged into 22 Parts, and 8 Schedules. As of 2019, it consists of a Preamble, approximately 470 Articles divided into 25 Parts, and 12 Schedules. This comprehensive framework clearly outlines the structure, organization, powers, and responsibilities of both the Central and state governments, while also defining the boundaries within which they operate, thereby reducing potential misunderstandings and conflicts.

3. Division of Powers:

- The Constitution delineates the distribution of powers between the Centre and the states through the Union List, State List, and Concurrent List found in the Seventh Schedule. The Union List contains 98 subjects (initially 97), the State List has 59 subjects (originally 66), and the Concurrent List includes 52 subjects (formerly 47). Both the Centre and the states are empowered to legislate on matters specified in the Concurrent List, but in cases of conflict, Central laws take precedence. Additionally, any subjects not included in these lists (residuary subjects) are allocated to the Centre.

4. Supremacy of the Constitution:

- The Constitution serves as the highest law of the land. Laws created by both the Central and state governments must align with its provisions. If they do not, they can be deemed invalid by the Supreme Court or high courts exercising their judicial review authority. Consequently, all branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial) at both levels must function within the boundaries set by the Constitution.

5. Rigid Constitution:

- The maintenance of power distribution as established by the Constitution, along with its supremacy, necessitates a rigid amendment process. Therefore, the Constitution is designed to be rigid, ensuring that any provisions related to the federal structure—specifically those concerning Centre-state relations and the organization of the judiciary—can only be modified through joint action by both Central and state governments. Amending these provisions requires a special majority in Parliament as well as approval from at least half of the state legislatures.

6. Independent Judiciary:

- The Constitution establishes an independent judiciary led by the Supreme Court for two key functions: to uphold the supremacy of the Constitution through judicial review and to resolve disputes between the Centre and states, or among states themselves. Various measures, such as job security for judges and fixed conditions of service, are included in the Constitution to ensure the judiciary operates independently from the government.

7. Bicameralism:

- The Constitution establishes a bicameral legislature composed of an Upper House (Rajya Sabha) and a Lower House (Lok Sabha). The Rajya Sabha represents the states of the Indian Federation, whereas the Lok Sabha represents the entire population of India. Although the Rajya Sabha holds less power, it plays a crucial role in maintaining federal balance by safeguarding state interests against potential overreach by the Centre.

Unitary Features of the Constitution of India

In addition to its federal characteristics, the Indian Constitution also exhibits several unitary or non-federal features:

1. Strong Centre:

- The division of powers is heavily skewed in favor of the Centre, which is not equitable from a federal perspective. First, the Union List contains more subjects than the State List. Second, more significant subjects have been allocated to the Union List. Third, the Central government holds overriding authority over the Concurrent List. Finally, the residuary powers are reserved for the Centre, whereas in the US, these powers belong to the states. Consequently, the Constitution empowers the Centre significantly.

2. States Not Indestructible:

- In contrast to other federations, states in India do not have a right to territorial integrity. The Parliament can unilaterally alter the area, boundaries, or names of states with a simple majority, rather than a special majority. This results in the Indian Federation being described as “an indestructible Union of destructible states,” whereas the American Federation is characterized as “an indestructible Union of indestructible states.”

3. Single Constitution:

- Typically, federations allow states to create their own constitutions separate from the central one. However, in India, states do not have this authority. The Indian Constitution itself encompasses not only the central governance structure but also the laws governing the states. Both levels of government must operate within this singular framework, with the exception of Jammu and Kashmir, which historically had its own constitution.

4. Flexibility of the Constitution:

- The process for amending the Constitution is less rigid compared to other federations. Many provisions can be altered through the unilateral action of Parliament, either by simple or special majority. Additionally, the power to initiate constitutional amendments is exclusive to the Centre, while in the US, states can also propose amendments.

5. No Equality of State Representation:

- State representation in the Rajya Sabha is based on population, leading to varying membership (from 1 to 31). In contrast, the US Senate adheres to the principle of equal representation, with two senators from each state, which acts as a safeguard for smaller states.

6. Emergency Provisions:

- The Constitution recognizes three types of emergencies: national, state, and financial. During such emergencies, the Central government gains extensive powers, and control is centralized, effectively transforming the federal structure into a unitary one without formal amendment. This transformation is uncommon in other federations.

7. Single Citizenship:

- Despite the dual polity structure, India’s Constitution, similar to Canada’s, establishes a system of single citizenship. There is only Indian citizenship without any separate state citizenship. All citizens enjoy equal rights throughout the country, unlike other federations such as the US, Switzerland, and Australia, which recognize both national and state citizenship.

8. Integrated Judiciary:

- India has a unified judicial system headed by the Supreme Court, which oversees both Central and state laws. This contrasts with the US, which features a dual court system enforcing federal laws through federal courts and state laws through state courts.

9. All-India Services:

- While both the Centre and the states maintain separate public services, India also has all-India services (such as IAS, IPS, and IFS) that serve both levels of government. These services are recruited and trained by the Centre, which retains ultimate control, thereby complicating the principle of federalism.

10. Integrated Audit Machinery:

- The Comptroller and Auditor-General of India is responsible for auditing accounts of both the Central government and the states. However, the appointment and removal of this official are done by the President without consulting the states, which limits the financial autonomy of the states. In contrast, the American Comptroller-General has no role in state accounts.

11. Parliament’s Authority Over State List:

- Even within their limited sphere of authority, states do not have complete control. The Parliament can legislate on matters in the State List if the Rajya Sabha passes a resolution for national interest, thus extending its legislative competence without needing to amend the Constitution.

12. Appointment of Governor:

- The Governor, serving as the head of a state, is appointed by the President and holds office at the President’s discretion, acting as a representative of the Centre. This allows the Centre to exercise control over the states. In contrast, the American system provides for an elected head of state, similar to the Canadian model adopted by India.

13. Integrated Election Machinery:

- The Election Commission oversees elections not only for the Central legislature but also for state legislatures. This body is appointed by the President, leaving states without any influence in this process. The US employs separate systems for conducting elections at federal and state levels.

14. Veto Over State Bills:

- The Governor has the authority to reserve specific bills passed by state legislatures for the President’s consideration, who can withhold assent not only initially but also upon subsequent re-presentation. This grants the President an absolute veto over state bills,

Critical Evaluation of the Federal System

It is evident that the Indian Constitution has diverged from traditional federal systems like those of the United States, Switzerland, and Australia, incorporating numerous unitary or non-federal features that favor the Centre. This has led constitutional experts to question the federal characteristics of the Indian Constitution. For instance, K.C. Wheare described it as “quasi-federal,” stating that the “Indian Union is a unitary state with subsidiary federal features rather than a federal state with subsidiary unitary features.”

K. Santhanam identified two key factors contributing to the increasing centralization of authority within the Constitution: (i) the dominance of the Centre in financial matters and the states’ reliance on Central grants, and (ii) the rise of a powerful planning commission that controlled state development processes. He argued that “India has practically functioned as a unitary state,” despite the formal and legal attempts of the Union and the states to operate as a federation.

However, several political scientists disagree with these assessments. Paul Appleby characterized the Indian system as “extremely federal,” while Morris Jones referred to it as “bargaining federalism.” Ivor Jennings noted that it functions as a “federation with a strong centralizing tendency,” suggesting that “the Indian Constitution is mainly federal with unique safeguards for enforcing national unity and growth.” Similarly, Alexandrowicz called India a “case sui generis,” indicating its unique nature, and Granville Austin described Indian federalism as “cooperative federalism.” He highlighted that, despite a strong Central government, state governments retain their authority and are not merely administrative agencies executing Central policies, characterizing Indian federalism as a “new kind of federation tailored to India’s specific needs.”

Regarding the nature of the Indian Constitution, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar stated during the Constituent Assembly, “The Constitution is a Federal Constitution in as much as it establishes a dual polity. The Union is not a league of states, united in a loose relationship, nor are the states the agencies of the Union, deriving powers from it. Both the Union and the states are created by the Constitution, both derive their respective authority from the Constitution.” He further noted that the Constitution is adaptable, allowing it to be both unitary and federal based on evolving needs and circumstances. Addressing criticisms of over-centralization, he remarked: “A serious complaint is made on the ground that there is too much centralisation and the states have been reduced to municipalities. This view is not only an exaggeration but is also based on a misunderstanding of the Constitution’s intent.”

In the Bommai case (1994), the Supreme Court affirmed that the Constitution is federal and characterized federalism as a “basic feature.” The Court emphasized: “The fact that greater power is conferred upon the Centre vis-à-vis the states does not mean that the states are mere appendages of the Centre. The states have an independent constitutional existence…The fact that during emergencies and in certain situations their powers may be curtailed does not undermine the essential federal nature of the Constitution.”

Indian federalism can be seen as a compromise between two conflicting considerations:

(i) the normal division of powers that allows states to maintain autonomy within their own jurisdictions, and

(ii) The necessity for national integrity and a strong Union government during exceptional circumstances.

Trends in the functioning of the Indian political system reflect this federal spirit, including:

(i) territorial disputes between states, such as the one between Maharashtra and Karnataka over Belgaum;

(ii) conflicts over river water sharing, exemplified by disputes between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu over Cauvery Water;

(iii) the rise of regional parties gaining power in states such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu;

(iv) the creation of new states to address regional aspirations, like Mizoram and Jharkhand;

(v) demands from states for increased financial grants from the Centre to meet development needs;

(vi) assertions of autonomy by states resisting Central interference; and

(vii) the Supreme Court imposing procedural limitations on the Centre’s use of Article 356 (President’s Rule in states).