Citizenship

Meaning and Significance of Citizenship

In India, as in any modern state, there are two categories of people: citizens and aliens. Citizens are fully integrated members of the Indian State, owing allegiance to it and enjoying all civil and political rights. Aliens are citizens of other countries and, as such, do not receive all civil and political rights of Indian citizens. Aliens are further categorized into friendly aliens, whose countries maintain cordial relations with India, and enemy aliens, who are citizens of countries at war with India. Enemy aliens have fewer rights, such as no protection against arrest and detention (Article 22).

Rights Exclusive to Citizens of India:

- Right against discriminationon grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth (Article 15).

- Right to equality of opportunityin matters of public employment (Article 16).

- Rights to freedom, including speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, and profession (Article 19).

- Cultural and educational rights(Articles 29 and 30).

- Right to votein elections for the Lok Sabha and state legislative assemblies.

- Right to contest electionsfor membership in Parliament and state legislatures.

- Eligibility for public office, including President, Vice-President, judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts, Governor, Attorney General, and Advocate General.

Citizens owe duties to the Indian State, such as paying taxes and respecting national symbols.

Unlike the USA, where only natural-born citizens can become President, both natural-born and naturalized citizens of India are eligible for the presidency.

Constitutional Provisions on Citizenship

The Constitution addresses citizenship in Articles 5 to 11 under Part II, outlining who would become citizens on January 26, 1950. It leaves acquisition and loss of citizenship post-1950 to be regulated by Parliament, resulting in the Citizenship Act of 1955, which has been amended over time.

Initial Categories of Citizenship:

- Persons domiciled in India who were born in India, had a parent born in India, or resided in India for five years before the Constitution began.

- Migrants from Pakistan who arrived before July 19, 1948, and lived in India continuously, or who arrived after and registered as citizens after six months’ residence.

- Those who migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947, but returned to resettle in India, meeting specific residency requirements.

- People of Indian origin residing outside India but born in undivided India and registered as citizens by Indian diplomatic representatives.

Other Constitutional Provisions:

- Persons voluntarily acquiring foreign citizenship cease to be Indian citizens.

- Current citizens remain so unless parliamentary law states otherwise.

- Parliament can legislate on citizenship acquisition, termination, and related matters.

Citizenship Act of 1955

The Citizenship Act of 1955 outlines the processes for obtaining and losing Indian citizenship:

Acquisition of Citizenship:

1. By Birth:

- Born in India between January 26, 1950, and July 1, 1987, confers citizenship by birth, regardless of parents’ nationality.

- Born in India between July 1, 1987, and December 3, 2004, requires at least one parent to be an Indian citizen.

- Born in India on or after December 3, 2004, must have both parents as Indian citizens, or one parent as a citizen while the other is not an illegal migrant.

Children of foreign diplomats and enemy aliens do not acquire citizenship by birth.These frameworks reflect India’s approach to nationality, balancing individual rights with national security and integration.

2. By Descent

A person born outside India on or after January 26, 1950, but before December 10, 1992, is considered a citizen of India by descent if their father was a citizen at the time of their birth. For those born outside India on or after December 10, 1992, citizenship is granted if either parent is an Indian citizen at the time of birth.

From December 3, 2004, individuals born outside India will not be considered citizens by descent unless their birth is registered at an Indian consulate within one year or with permission from the Central Government after that period. An application for the registration of a minor child’s birth at an Indian consulate requires a written undertaking from the parents confirming the child does not hold the passport of another country. Furthermore, a minor who is a citizen of India by descent and holds citizenship of another country will lose Indian citizenship if they do not renounce the other citizenship within six months of reaching adulthood.

3. By Registration

The Central Government can register as a citizen of India any person (not being an illegal migrant) belonging to certain categories:

– Individuals of Indian origin who have been ordinarily resident in India for seven years before applying.

– Individuals of Indian origin residing outside India.

– Persons married to Indian citizens and living in India for seven years prior to application.

– Minor children of Indian citizens.

– Adults whose parents are registered citizens of India.

– Individuals whose parents were previously citizens of independent India and have resided in India for twelve months before applying.

– Individuals registered as Overseas Citizens of India for five years and residing in India for twelve months before application.

All individuals in these categories must take an oath of allegiance prior to registration.

4. By Naturalization

The Central Government may grant naturalization (a certificate of citizenship) to any eligible person (not an illegal migrant) if they meet the following criteria:

– They are not a citizen of any country that prevents Indian citizens from obtaining citizenship there.

– If they are a citizen of another country, they must renounce that citizenship upon acceptance of their application for Indian nationality.

– They must have resided in India or been in government service in India for the twelve months immediately preceding their application.

– Over the preceding fourteen years, they should have lived in India or served in a government capacity, totaling no less than eleven years.

– They must demonstrate good character.

– They must have adequate knowledge of a language specified in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution.

– They must intend to reside in India or work for a government or organization of which India is a member.

The government can waive any of these conditions for individuals who have rendered distinguished service in fields such as science, art, literature, or human progress. All naturalized citizens must also take an oath of allegiance to the Constitution of India.

5. By Incorporation of Territory

When a foreign territory becomes part of India, the Government of India designates which individuals from that territory will be granted Indian citizenship. For example, when Pondicherry became part of India, the Government issued the Citizenship (Pondicherry) Order in 1962 under the Citizenship Act of 1955.

6. Special Provisions for Persons Covered by the Assam Accord

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 1985 introduced special provisions for citizens as outlined in the Assam Accord:

– Persons of Indian origin who entered Assam before January 1, 1966, from Bangladesh and have resided there since are deemed citizens of India as of that date.

– Individuals who migrated to Assam between January 1, 1966, and March 25, 1971, and were identified as foreigners must register as citizens. Those registered will be recognized as Indian citizens ten years after their identification as foreigners, retaining the same rights as citizens except for the right to vote throughout that period.

Citizenship by Birth and Descent in India

Mode | Date of Birth | Conditions for Citizenship | ||

By Birth | January 26, 1950 – June 30, 1987 | Individual is a citizen of India irrespective of the nationality of parents. | ||

On or after July 1, 1987 | Individual is a citizen if either parent is a citizen of India at the time of birth. | |||

On or after December 3, 2004 | Individual is a citizen if both parents are Indian citizens or one parent is a citizen and the other is not an illegal migrant at the time of birth. | |||

Mode | Period | Conditions for Citizenship | ||

By Descent | January 26, 1950 – December 9, 1992 | Individual born outside India is a citizen if father was an Indian citizen at the time of birth. | ||

On or after December 10, 1992 | Individual is a citizen if either parent is an Indian citizen at the time of birth. | |||

On or after December 3, 2004 | Parents must declare that the minor child does not hold a passport of another country and must register the birth at an Indian consulate within one year. If registration is delayed, approval from the Central Government is required. | |||

Loss of Citizenship

The Citizenship Act of 1955 defines three ways individuals can lose their citizenship, whether acquired under the Act or under the Constitution:

1. By Renunciation:

An Indian citizen of full age and capacity may voluntarily declare their intention to renounce their citizenship. Upon registration of this declaration, they cease to be a citizen of India. If this declaration is made during a time of war involving India, its registration will be suspended. Additionally, if a person renounces their citizenship, any minor children will also lose their Indian citizenship. However, if the child reaches the age of eighteen, they may resume Indian citizenship.

2. By Termination:

An Indian citizen automatically loses their citizenship if they voluntarily acquire the citizenship of another country. This termination does not apply during a time of war involving India.

3. By Deprivation:

Deprivation refers to the compulsory termination of Indian citizenship by the Central Government under specific circumstances. A citizen may lose their citizenship if:

(a) The citizenship was obtained through fraudulent means.

(b) The citizen has demonstrated disloyalty to the Constitution of India.

(c) The citizen has unlawfully engaged in trade or communication with the enemy during wartime.

(d) The citizen has been imprisoned in any country for two years within five years following their registration or naturalization.

(e) The citizen has resided outside of India for a continuous period of seven years.

These conditions are outlined to ensure that citizenship is maintained by individuals who adhere to the obligations and responsibilities associated with being a citizen of India.

Loss of Citizenship in India

Mode | Conditions | Details |

By Renunciation | Voluntary declaration renouncing citizenship. | Minor children also lose citizenship but can re-apply once they attain 18 years of age. |

By Termination | Acquisition of citizenship of another country voluntarily. | Does not apply during times of war involving India. |

By Deprivation | Citizenship can be revoked under specific grounds: | 1. Fraud in the acquisition process. |

Single Citizenship

Although the Indian Constitution establishes a federal structure and envisions a dual polity (comprising the Centre and the states), it provides for only a single citizenship: Indian citizenship. Citizens of India owe their allegiance solely to the Union, with no separate state citizenship. In contrast, other federal systems, such as those in the USA and Switzerland, allow for double citizenship.

In the United States, individuals are not only citizens of the USA but also citizens of the specific state in which they reside. This means they owe allegiance to both the national and state governments and are entitled to two sets of rights—one from the national government and another from the state government. Such a system can introduce potential inequalities, as a state may favor its own citizens regarding voting rights, eligibility for public office, and other privileges. The single citizenship system in India helps avoid these issues.

In India, all citizens, regardless of the state in which they are born or reside, enjoy the same civil and political rights throughout the country without discrimination. However, this general principle of non-discrimination has some exceptions:

1. Parliamentary Authority:

Under Article 16, Parliament can require residence within a state or union territory as a condition for certain jobs or positions. This was implemented through the Public Employment (Requirement as to Residence) Act of 1957, which allowed the Government of India to set residency qualifications for non-Gazetted posts in Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, and Tripura. As this Act expired in 1974, only Andhra Pradesh and Telangana continue to have such provisions.

2. Discrimination Provisions:

The Constitution prohibits discrimination against any citizen based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth (Article 15), but not on the grounds of residence. This means states can offer benefits or preferences to their residents, such as fee concessions for education.

3. Protection of Tribal Interests:

The right to freedom of movement and residence (Article 19) is subject to restrictions for protecting the interests of scheduled tribes. This means outsiders may have limited rights to enter, reside in, or settle in tribal areas. These restrictions aim to safeguard the unique culture, language, customs, and livelihoods of tribal communities from exploitation.

4. Jammu and Kashmir Provisions:

Until 2019, the state legislature of Jammu and Kashmir had the authority to define permanent residents and grant them special rights and privileges related to employment, property acquisition, settlement, and scholarships. This provision was established under Article 35-A, which was inserted into the Constitution by “The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954,” issued by the President under Article 370, granting special status to Jammu and Kashmir. However, in 2019, this special status was revoked with a new presidential order, “The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019,” which superseded the 1954 order.

The Constitution of India, similar to Canada, supports a system of single citizenship and aims to provide uniform rights for the people of India, fostering a sense of fraternity and unity within the nation while striving to build an integrated society. Nonetheless, India has continued to experience communal riots, class conflicts, caste disputes, linguistic tensions, and ethnic clashes. Consequently, the founding fathers’ and Constitution-makers’ vision of a united and integrated Indian nation remains a work in progress.

Overseas Citizenship of India

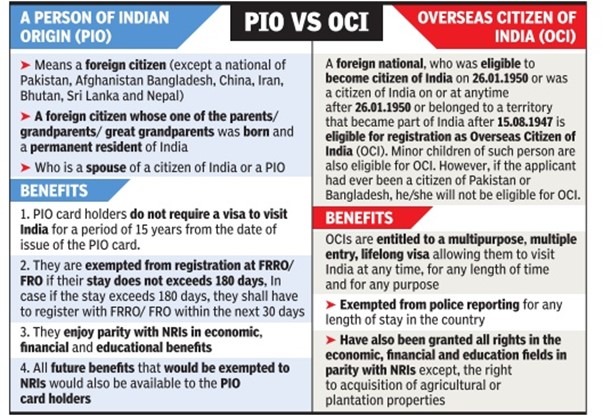

In September 2000, the Government of India, specifically the Ministry of External Affairs, established a High-Level Committee on the Indian Diaspora, chaired by L.M. Singhvi. The committee’s mandate was to conduct a thorough study of the global Indian Diaspora and recommend measures to foster a positive relationship with them. In January 2002, the committee submitted its report, suggesting an amendment to the Citizenship Act (1955) to allow for dual citizenship for Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) from specific countries.

As a result, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2003 was enacted, which provided for the acquisition of Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) for PIOs from 16 specified countries, excluding Pakistan and Bangladesh. The amendment also removed all provisions related to Commonwealth Citizenship from the original Act.

Subsequently, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2005 expanded the eligibility for OCI to PIOs from all countries, except for Pakistan and Bangladesh, provided that their home countries allowed dual citizenship under their laws. It is important to clarify that OCI does not equate to dual citizenship; the Indian Constitution prohibits dual citizenship or dual nationality, as stated in Article 9.

In 2015, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act further modified the provisions related to OCI in the Principal Act. It introduced a new classification termed “Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder” by merging the pre-existing PIO card scheme and the OCI card scheme.

The PIO card scheme was originally introduced on August 19, 2002, followed by the OCI card scheme on December 2, 2005. Both schemes operated concurrently, but the increasing popularity of the OCI card led to confusion among applicants. To simplify the process and enhance facilities for applicants, the Government of India decided to create a single scheme that incorporated positive aspects of both.

Thus, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2015 was enacted, which rescinded the PIO scheme effective January 9, 2015. It also established that all existing PIO cardholders would be recognized as OCI cardholders as of the same date.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2015 replaced the term “Overseas Citizen of India” with “Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder” and included the following provisions in the Principal Act:

Overseas Citizenship of India

I. Registration of Overseas Citizen of India Cardholders

1. The Central Government has the authority to register individuals as Overseas Citizens of India (OCI) cardholders upon application. This includes:

- Persons of full age and capacitywho are citizens of another country but were citizens of India at any time after the commencement of the Constitution.

- Persons who are citizens of another country but would have been eligible for Indian citizenship at the start of the Constitution.

- Individuals who are citizens of another nation but belonged to a territory that became part of India after August 15, 1947.

- Children, grandchildren, or great-grandchildren of individuals mentioned above.

2. The Central Government may also register:

- Minor children of any individual mentioned in the above categories.

- Minor children whose both parents are Indian citizens or one parent is an Indian citizen.

- Spouses of foreign origin who are married to Indian citizens or OCI cardholders, provided the marriage has been registered and has lasted for at least two years prior to the application.

3. Those whose parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents were citizens of Pakistan, Bangladesh, or any other designated country by the Central Government are ineligible for registration as OCI cardholders.

- The Central Government may designate a date from which existing Persons of Indian Origin cardholders will be recognized as OCI cardholders.

- The Central Government can grant registration as an OCI cardholder in special circumstances, which must be documented in writing.

II. Rights of Overseas Citizens of India Cardholders

1. An OCI cardholder is entitled to certain rights as specified by the Central Government.

2. However, OCI cardholders do not enjoy the following rights that are reserved for Indian citizens:

- The right to equality of opportunity in public employment.

- Eligibility to be elected as President or Vice President.

- Eligibility for appointment as a Judge of the Supreme Court or High Court.

- The right to register as a voter.

- Eligibility to be a member of the House of the People or the Council of States.

- Eligibility to serve in the State Legislative Assembly or State Legislative Council.

- Eligibility for public service positions under the Union or any State, except as specified by the Central Government.

III. Renunciation of Overseas Citizenship

- If an OCI cardholder chooses to renounce their status, they must declare this intention in the prescribed manner. Upon registration of this declaration, they will cease to be an OCI cardholder.

- If a person loses their OCI status, their foreign spouse and any minor children registered as OCI cardholders will also lose their OCI status.

IV. Cancellation of Registration as Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder

The Central Government may cancel the OCI registration if it finds that:

- The registration was obtained through fraud, false representation, or concealment of material facts.

- The OCI cardholder has expressed disloyalty to the Constitution of India.

- The OCI cardholder has unlawfully traded or communicated with an enemy during any time of war involving India.

- The OCI cardholder has been sentenced to a minimum of two years in prison within five years of registration.

- Cancellation is necessary for the sovereignty and integrity of India, security interests, international relations, or public welfare.

- The marriage of an OCI cardholder has been dissolved or, while married, they have married another person.

This framework for Overseas Citizenship of India reflects the government’s efforts to connect with the Indian diaspora while ensuring that their rights and responsibilities are clearly defined.

Articles Related to Citizenship at a Glance

Here’s a summary of the articles in the Indian Constitution that pertain to citizenship:

Article No. | Subject Matter |

5 | Citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution |

6 | Rights of citizenship of certain persons who have migrated to India from Pakistan |

7 | Rights of citizenship of certain migrants to Pakistan |

8 | Rights of citizenship of certain persons of Indian origin residing outside India |

9 | Persons voluntarily acquiring citizenship of a foreign state shall not be citizens |

10 | Continuance of the rights of citizenship |

11 | Parliament’s power to regulate the right of citizenship by law |