Centre-State Relations

The Constitution of India, with its federal framework, allocates legislative, executive, and financial powers between the Centre and the states. However, it does not divide judicial authority, as it establishes an integrated judicial system that enforces both Central and state laws. Although both the Centre and the states are sovereign in their respective domains, effective functioning of the federal system requires maximum harmony and cooperation between them. Therefore, the Constitution includes detailed provisions to govern the various aspects of Centre-state relations, which can be categorized into three main areas:

- Legislative relations

- Administrative relations

- Financial relations

Legislative Relations

Articles 245 to 255 in Part XI of the Constitution pertain to the legislative relations between the Centre and the states, along with additional provisions that address this subject. Similar to other federal constitutions, the Indian Constitution separates legislative powers between the Centre and the states based on both territory and subjects. The legislative relations can be divided into four key aspects:

1. Territorial Extent of Central and State Legislation:

- The Parliament can legislate for the entire territory of India or any part of it, including states, union territories, and any new areas that fall within India’s territory.

- A state legislature can make laws applicable only within the state, unless there is a sufficient connection to the legislation’s subject matter.

- The Parliament alone has the authority to legislate extraterritorially, allowing its laws to apply to Indian citizens and their properties worldwide.

However, there are specific limitations on the territorial jurisdiction of the Parliament:

- The President has the power to create regulations for the governance of certain union territories, giving these regulations the same effect as an act of Parliament and allowing them to amend or repeal parliamentary acts.

- Governors can direct that a parliamentary act does not apply to scheduled areas within a state or that it applies with certain modifications.

- The Governor of Assam can also specify that an act does not apply to tribal areas (autonomous districts) in the state, with similar powers held by the President regarding tribal regions in Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

2. Distribution of Legislative Subjects:

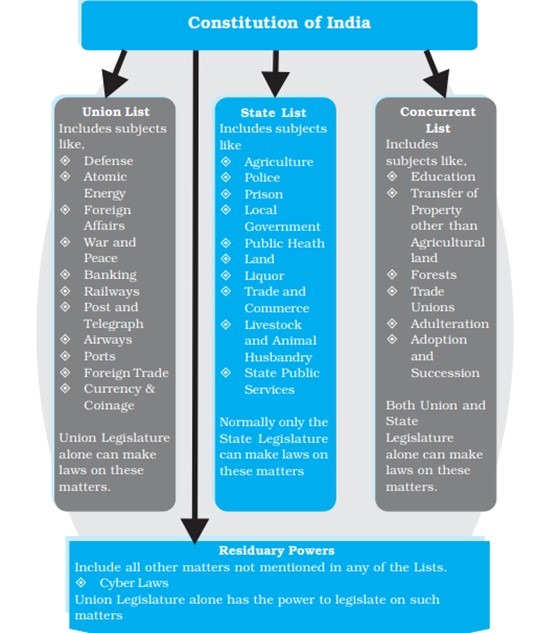

The Constitution outlines a three-fold distribution of legislative subjects between the Centre and the states, defined in the Seventh Schedule:

- Union List (List-I): Comprises subjects for which only the Parliament has the exclusive power to legislate. This list currently contains 98 subjects (originally 97), including defense, foreign affairs, currency, atomic energy, and inter-state trade.

- State List (List-II): Details subjects for which the state legislatures have exclusive powers under normal circumstances. This list presently includes 59 subjects (originally 66), covering areas such as public order, health, agriculture, and local governance.

- Concurrent List (List-III): Allows both Parliament and state legislatures to make laws on the subjects listed, which currently includes 52 subjects (originally 47) such as criminal law, civil procedure, marriage, and labor welfare. The 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 added five subjects from the State List to the Concurrent List: education, forests, weights and measures, protection of wild animals and birds, and the administration of justice.

- The Parliament has the authority to legislate on any matters within the territory of India that are not included in the State List, particularly concerning Union Territories.

- The 101st Amendment Act of 2016 established provisions for Goods and Services Tax (GST), permitting both Parliament and state legislatures to legislate on GST matters, while the Parliament maintains exclusive power over inter-state trade and commerce related to GST.

- Residual powers, or powers not specified in any of the three lists, reside with Parliament, which includes the authority to impose residual taxes.

From this structure, it’s clear that subjects of national significance and those requiring uniform legislation throughout the country are included in the Union List, while subjects of local importance reside in the State List. The Concurrent List accommodates matters where uniformity is desired but not imperative.

In comparison, the US Constitution enumerates only the powers of the federal government, leaving residual powers to the states. Similarly, the Australian Constitution adopts a single enumeration of powers like the US model. In Canada, however, there is a dual enumeration of powers at both the federal and provincial levels, with residual powers vested in the Centre.

The Government of India Act of 1935 also included a three-fold enumeration of powers, which inspired the present Constitution, although it notably did not assign residuary powers to either federal or provincial legislatures; instead, these powers were given to the Governor-General. In this aspect, India follows the Canadian precedent.

The Constitution ensures the dominance of the Union List over both the State List and the Concurrent List. In the event of overlap, the Union List prevails, as does the Concurrent List over the State List. Therefore, when conflicts arise between Central and state laws on subjects in the Concurrent List, Central

3. Parliamentary Legislation in the State Field

The distribution of legislative powers between the Centre and the states is meant to function normally under standard conditions. However, during extraordinary times, this distribution can be modified or suspended. The Constitution grants Parliament the authority to legislate on matters listed in the State List under any of the following five unusual circumstances:

1. When Rajya Sabha Passes a Resolution: If the Rajya Sabha declares that it is necessary for the national interest for Parliament to legislate on a matter in the State List, Parliament gains the authority to do so. This resolution must be supported by two-thirds of the members present and voting, and it remains valid for one year, renewable indefinitely for one year at a time. Laws enacted under this provision become ineffective six months after the resolution lapses. This does not obstruct a state legislature’s ability to legislate on the same issue, but in cases of conflict between state law and parliamentary law, the latter prevails.

2. During a National Emergency: While a national emergency is in effect, Parliament can legislate on matters in the State List, including goods and services tax. Similar to the previous scenario, any laws made in this context become inoperative six months after the emergency ends. State legislatures retain the ability to legislate on the same matters, but again, in the event of any conflict, the law passed by Parliament takes precedence.

3. When States Make a Request: If the legislatures of two or more states pass resolutions requesting Parliament to enact laws on specific matters from the State List, Parliament can legislate accordingly. Such laws apply exclusively to the states that passed the resolutions, although other states can adopt the law later. Once Parliament legislates on this matter, the relevant state legislature loses its power to legislate on that issue, effectively ceding its authority to Parliament, which then becomes the sole entity permitted to legislate on that topic.

Examples of laws enacted under this provision include the Prize Competition Act of 1955, the Wild Life (Protection) Act of 1972, the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act of 1974, the Urban Land (Ceiling and Regulation) Act of 1976, and the Transplantation of Human Organs Act of 1994.

4. To Implement International Agreements: Parliament has the authority to legislate on matters in the State List to fulfill international treaties, agreements, or conventions. This provision allows the Central government to meet its international obligations.

Examples of legislation passed for this purpose include the United Nations (Privileges and Immunities) Act of 1947, the Geneva Convention Act of 1960, the Anti-Hijacking Act of 1982, and various environmental laws and regulations pertaining to TRIPS.

5. During President’s Rule: When President’s Rule is imposed in a state, Parliament can legislate on matters in the State List relevant to that state. Such laws will remain in effect even after the period of President’s Rule ends. However, the state legislature retains the power to amend, repeal, or re-enact such laws.

Article | Parliamentary Legislation | Process | Other Facts | Status of Laws Made |

Art. 249 | If ‘Rajya Sabha’ passes a resolution stating it is necessary in the ‘national interest’ | Resolution must be supported by 2/3rd of the members present and voting | Resolution remains in force for 1 year; can be renewed any number of times, but each renewal not more than 1 year; State Legislatures can also make laws | Parliamentary law ceases 6 months after the resolution expires; in case of inconsistency, Parliamentary law prevails |

Art. 250 | During National Emergency | No special resolution needed; Parliament can legislate on State subjects | Applies during the period of National Emergency | Laws remain in force for 6 months after the expiry of Emergency; Parliamentary law prevails in case of inconsistency |

Art. 252 | States make a request | Two or more State Legislatures pass a resolution | Other states can adopt the law by passing a similar resolution in their legislatures | Law applies only to those states that passed/adopted the resolution; Can be amended or repealed only by Parliament |

Art. 253 | To implement international agreements, treaties, or conventions | No specific process outlined | Related to external affairs and international obligations | Parliament can legislate even on State subjects to implement treaties |

Art. 356 | When President’s Rule is imposed in a state | Parliament assumes the power to legislate for the state | Applies only to the state under President’s Rule | Laws remain in force even after President’s Rule ends; Can be repealed, altered, or re-enacted by the State Legislature |

4. Centre’s Control over State Legislation

Beyond the power of Parliament to directly legislate on state issues during exceptional circumstances, the Constitution also empowers the Centre to exert control over state legislative matters in several ways:

(i) The governor can reserve specific bills passed by the state legislature for the President’s consideration, who possesses absolute veto power over them.

(ii) Bills concerning particular matters in the State List can only be introduced in the state legislature with the prior approval of the President (for instance, bills that impose restrictions on trade and commerce).

(iii) The Centre has the authority to require states to reserve money bills and other financial legislation for the President’s consideration during a financial emergency.

From the aforementioned provisions, it is evident that the Constitution establishes the Centre’s superior position within the legislative framework. In this context, the Sarkaria Commission on Centre-State Relations (1983–88) remarks: “The rule of federal supremacy is a technique to avoid absurdity, resolve conflict and ensure harmony between the Union and state laws. If this principle of Union supremacy is disregarded, the consequences could be detrimental. The potential for interference, conflict, legal chaos, and confusion caused by conflicting laws could bewilder the common citizen. A unified legislative policy and uniformity on significant issues of mutual Union-state concern could be severely impeded. Therefore, the principle of federal supremacy is essential for the effective functioning of the federal system.”

Administrative Relations

Articles 256 to 263 in Part XI of the Indian Constitution outline the administrative relations between the Centre and the states, along with additional articles that address similar issues.

Distribution of Executive Powers

The distribution of executive power mirrors the distribution of legislative powers between the Centre and the states, with a few exceptions. The executive power of the Centre encompasses the entire territory of India, specifically including:

- matters where Parliament has exclusive legislative authority (i.e., subjects listed in the Union List), and

- the exercise of rights, authority, and jurisdiction granted by any treaty or agreement. Conversely, state executive power is similarly localized to the state’s territory regarding matters where the state legislature possesses exclusive legislative authority (i.e., subjects in the State List).

For matters where both Parliament and state legislatures can legislate (i.e., subjects in the Concurrent List), the executive power primarily resides with the states unless a specific constitutional provision or law passed by Parliament assigns that power to the Centre. Consequently, while a law concerning a concurrent subject may be enacted by Parliament, its execution typically falls to the states unless explicitly stated otherwise by the Constitution or Parliament.

Obligation of States and the Centre

The Constitution imposes two restrictions on state executive powers to facilitate the Centre’s uninterrupted exercise of its executive authority. Therefore, the executive power of each state must be exercised in a manner that:

(a) Ensures compliance with laws enacted by Parliament and any existing applicable laws within the state, and

(b) Does not obstruct or adversely affect the exercise of the Centre’s executive power within the state. The first obligation establishes a general duty for the states, while the second imposes a specific requirement that states refrain from hindering the executive authority of the Centre.

Articles Related to Centre-State Legislative Relations at a Glance

Article No. | Subject Matter |

245 | Extent of laws made by Parliament and by the legislatures of states |

246 | Subject-matter of laws made by Parliament and by the legislatures of states |

246A | Special provision with respect to goods and services tax |

247 | Power of Parliament to provide for the establishment of certain additional courts |

248 | Residuary powers of legislation |

249 | Power of Parliament to legislate with respect to a matter in the state list in the national interest |

250 | Power of Parliament to legislate with respect to any matter in the state list if a Proclamation of Emergency is in operation |

251 | Inconsistency between laws made by Parliament under articles 249 and 250 and laws made by the legislatures of states |

252 | Power of Parliament to legislate for two or more states by consent and adoption of such legislation by any other state |

253 | Legislation for giving effect to international agreements |

254 | Inconsistency between laws made by Parliament and laws made by the legislatures of states |

255 | Requirements as to recommendations and previous sanctions to be regarded as matters of procedure only |

In instances where the Centre’s directions are issued to the states, the executive power of the Centre extends to ensuring compliance with those directions. The nature of this coercion is emphasized by Article 365, which states that if a state fails to comply with or implement any directions given by the Centre, the President may determine that the state’s government cannot operate according to the Constitution’s provisions. Consequently, this situation could lead to the imposition of President’s Rule in the state under Article 356.

Centre’s Directions to the States

In addition to the previously discussed provisions, the Centre is authorized to direct states regarding the exercise of their executive powers in specific areas:

(i) The construction and maintenance of communication systems deemed of national or military importance.

(ii) Measures for the protection of railways within the state.

(iii) Providing facilities for instructing children from linguistic minority groups in their mother tongue at the primary education level.

(iv) Developing and implementing programs for the welfare of Scheduled Tribes in the state.

The coercive authority behind these Central directives, as specified in Article 365, applies in these cases as well.

Mutual Delegation of Functions

Legislative power distribution between the Centre and the states is rigid; therefore, the Centre cannot delegate its legislative powers to states, and a single state cannot request Parliament to legislate on state subjects. Although executive power generally follows legislative distribution, this rigid division may lead to conflicts. To address this, the Constitution allows for the mutual delegation of executive functions.

The President can assign certain executive functions of the Centre to a state government with its consent, while a governor may similarly delegate functions of the state to the Centre with approval. This delegation can be either conditional or unconditional.

Moreover, the Constitution permits the Centre to delegate executive functions to states without their consent, but this is done through parliamentary action. Consequently, Parliament can assign powers or impose duties on a state regarding subjects in the Union List, regardless of the state’s agreement. However, state legislatures do not possess this authority.

Overall, mutual delegation of functions can occur through agreement or legislation, with the Centre able to use both methods while states are limited to the former.

Cooperation between the Centre and States

The Constitution includes several provisions to foster cooperation and coordination between the Centre and the states:

(i) Parliament can adjudicate any disputes or complaints concerning the use, distribution, and control of waters from inter-state rivers and river valleys.

(ii) The President may establish an Inter-State Council under Article 263 to investigate and discuss shared interests between the Centre and the states. This Council was established in 1990.

(iii) Public acts, records, and judicial proceedings from the Centre and all states must be given full faith and credit throughout India.

(iv) Parliament can designate an authority to facilitate interstate trade, commerce, and interaction, although no such authority has yet been appointed.

All-India Services

In addition to separate public services for the Centre and the states, India has All-India Services, such as the IAS, IPS, and IFS. These services allow their members to hold key positions under both levels of government while serving in various capacities. Although they are recruited and trained by the Centre, the ultimate control of these services lies with the Central government, while immediate oversight rests with the state governments.

The Indian Civil Service (ICS) was replaced by the IAS, and the Indian Police (IP) was replaced by the IPS in 1947, with both services recognized as All-India Services in the Constitution. The Indian Forest Service (IFS) was established in 1966 as the third All-India Service. Article 312 empowers Parliament to create additional All-India Services based on a resolution from the Rajya Sabha.

These three services, despite being distributed across different states, constitute a single service with common rights, status, and uniform pay scales nationwide. Although the existence of All-India Services may seem to infringe upon the autonomy of states under the federal principle, they are justified because they:

(i) Help maintain high administrative standards at both the Centre and the states. (ii) Ensure uniformity in the administrative system nationwide. (iii) Facilitate cooperation and coordination on common interests between the Centre and the states.

While advocating for All-India Services in the Constituent Assembly, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar remarked that a dual polity within a federal system typically requires a dual service as well. He emphasized that strategic administrative positions necessitate civil servants of high caliber, and although states have the right to form their own services, an all-India service should exist for strategic roles, recruited based on common qualifications and uniform pay scales throughout the Union.

Public Service Commissions

In the context of public service commissions, the following provisions govern Centre-state relations:

- The Chairman and members of a state public service commission are appointed by the state governor, but they can only be removed by the President.

- Parliament may establish a Joint State Public Service Commission (JSPSC) for two or more states upon the request of the relevant state legislatures. The President appoints the Chairman and members of the JSPSC.

- The Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) can assist a state upon the request of the state governor, with the President’s approval.

- The UPSC can facilitate joint recruitment schemes for services requiring candidates with special qualifications when requested by two or more states.

Integrated Judicial System

Despite India’s federal structure, it lacks a dual system of justice. Instead, the Constitution establishes an integrated judicial system with the Supreme Court at its apex and state high courts beneath it. This unified court system administers both Central and state laws to minimize procedural diversity.

Judges of state high courts are appointed by the President, with consultations involving the Chief Justice of India and the governor of the state. The President also has the authority to transfer and remove these judges. Additionally, Parliament can establish a common high court for more than one state, as seen with the high courts serving both Maharashtra and Goa or Punjab and Haryana.

Relations During Emergencies

- During a national emergency (Article 352), the Centre can issue executive directions to states on any matter. State governments remain under the Centre’s complete control without being suspended.

- Under Article 356, when President’s Rule is imposed, the President can assume the functions of the state government and the powers of the Governor or any other state executive authority.

- During a financial emergency (Article 360), the Centre can direct states to adhere to financial propriety and issue other relevant directives, including salary reductions for state employees.

Other Provisions

The Constitution includes additional provisions that enable the Centre to oversee state administration:

- Article 355 imposes two responsibilities on the Centre: (a) to protect each state from external aggression and internal disturbances, and (b) to ensure every state’s governance aligns with constitutional provisions.

- The governor of each state is appointed by the President and serves at the President’s discretion. As the state’s constitutional head, the governor also acts as the Centre’s representative and submits periodic reports on state administrative matters.

- Although the state election commissioner is appointed by the governor, removal is the prerogative of the President.

Extra-Constitutional Devices

Beyond constitutional mechanisms, extra-constitutional methods promote cooperation between the Centre and the states, which include various advisory bodies and conferences at the central level.

Key non-constitutional advisory bodies involve the NITI Aayog (which replaced the Planning Commission), the National Integration Council, and other councils related to health, local governance, and regional development.

Significant conferences, held either annually or periodically to enhance Centre-state dialogue on various issues, include:

- The Governors’ Conference (presided over by the President)

- The Chief Ministers’ Conference (presided over by the Prime Minister)

- The Chief Secretaries’ Conference (presided over by the Cabinet Secretary)

- The Inspector-General of Police Conference

- The Chief Justices’ Conference (presided over by the Chief Justice of India)

- The Vice-Chancellors’ Conference

- The Home Ministers’ Conference (presided over by the Central Home Minister)

- The Law Ministers’ Conference (presided over by the Central Law Minister)

Financial Relations

- Articles 268 to 293 in Part XII of the Indian Constitution govern the financial relations between the Centre and the states. These provisions can be categorized under the following headings:

- Allocation of Taxing Powers

- The Constitution outlines the division of taxing powers between the Centre and the states as follows:

- Exclusive Power of Parliament: The Parliament has the sole authority to levy taxes on subjects specified in the Union List, which encompasses 13 items.

- Exclusive Power of State Legislatures: State legislatures possess exclusive powers to levy taxes on subjects enumerated in the State List, totaling 18 items.

- No Tax Entries in the Concurrent List: The Concurrent List does not include any tax items, meaning concurrent jurisdiction is not applicable to tax legislation. However, the 101st Amendment Act of 2016 introduced a special provision for goods and services tax (GST), granting both Parliament and State Legislatures concurrent powers to legislate on GST.

- Residuary Power of Taxation: The Parliament holds the residuary power of taxation, which allows it to impose taxes not listed in any of the three lists. This authority has been utilized to impose taxes such as gift tax, wealth tax, and expenditure tax.

| List | Taxation Power |

| Union List | Parliament has exclusive power to levy taxes (Total: 13 major taxes) – more remunerative |

| State List | State Legislature has power to levy taxes (Total: 18 taxes) – less remunerative |

| Concurrent List | No taxation power under normal circumstances. Exception: 101st Constitutional Amendment – special provision for GST, giving concurrent power to both Parliament and State Legislatures |

| Residuary Power | Union (Parliament has exclusive power to legislate on residuary matters including taxation) |

Articles Related to Centre-State Administrative Relations at a Glance

| Article No. | Subject Matter |

| 256 | Obligation of states and the Union |

| 257 | Control of the Union over states in certain cases |

| 257A | Assistance to states by deployment of armed forces or other forces of the Union (Repealed) |

| 258 | Power of the Union to confer powers, etc., on states in certain cases |

| 258A | Power of the states to entrust functions to the Union |

| 259 | Armed Forces in states in Part B of the First Schedule (Repealed) |

| 260 | Jurisdiction of the Union in relation to territories outside India |

| 261 | Public acts, records, and judicial proceedings |

| 262 | Adjudication of disputes relating to waters of interstate rivers or river valleys |

| 263 | Provisions relating to an inter-state Council |

The Constitution of India makes a clear distinction between the authority to levy and collect taxes and the authority to allocate the revenue generated from those taxes. For instance, while income tax is levied and collected by the Centre, its proceeds are shared between both the Centre and the states.

Additionally, the Constitution imposes specific restrictions on the taxing powers of the states:

1. Limits on Professional Taxes: A state legislature can impose taxes on professions, trades, callings, and employments, but the total annual tax payable by any individual cannot exceed ₹2,500.

2. Prohibition on Certain Taxes: States are prohibited from taxing the supply of goods or services in two scenarios:

When such supply occurs outside the state.

When the supply happens in the course of import or export. Furthermore, Parliament has the authority to set principles for determining when a supply occurs outside the state or during import/export.

3. Electricity Taxation: States can impose taxes on the consumption or sale of electricity, but they cannot tax electricity that is (a) consumed by the Centre or sold to the Centre, or (b) used for the construction, maintenance, or operation of any railway by the Centre or railway company.

4. Water and Electricity Taxation: States may levy taxes on water or electricity that is stored, generated, consumed, distributed, or sold by any authority established by Parliament for the regulation or development of inter-state rivers or river valleys. However, such legislation must be reserved for the President’s consideration and require his assent to be effective.

Distribution of Tax Revenues

The 80th Amendment Act of 2000 and the 101st Amendment Act of 2016 brought significant changes to the distribution of tax revenues between the Centre and the states.

The 80th Amendment was enacted to implement the recommendations of the 10th Finance Commission, which proposed that 29% of the total income from specific central taxes and duties be allocated to the states. This “Alternative Scheme of Devolution” retroactively took effect from April 1, 1996, and adjusted taxes like Corporation Tax and Customs Duties to align with Income Tax regarding their distribution to states.

The 101st Amendment introduced a new tax regime known as the Goods and Services Tax (GST). It granted concurrent taxing powers to both Parliament and the State Legislatures for levying GST on transactions involving the supply of goods and services. The GST replaces several indirect taxes imposed by both Union and State Governments and aims to eliminate the cascading effect of taxes, creating a unified national market. This Amendment subsumed various central indirect taxes like Central Excise Duty, Service Tax, and others, as well as state taxes such as Value Added Tax/Sales Tax and Entertainment Tax, among others. It also repealed Article 268-A and Entry 92-C in the Union List related to service tax.

After these amendments, the current position regarding the distribution of tax revenues is as follows:

A. Taxes Levied by the Centre but Collected and Appropriated by the States (Article 268): This includes stamp duties on financial instruments such as cheques and insurance policies, with proceeds assigned to the respective states and not included in the Consolidated Fund of India.

B. Taxes Levied and Collected by the Centre but Assigned to States (Article 269): This includes taxes on sales or purchases of goods during inter-state commerce and taxes on goods consignments in inter-state trade. The net proceeds from these taxes are assigned to the states based on principles set by Parliament.

C. GST in Inter-State Trade (Article 269-A): GST on inter-state transactions is levied and collected by the Centre but shared with the states according to guidelines established by Parliament upon recommendations from the GST Council. Parliament can also set rules to determine where the supply occurs in inter-state commerce.

D. Taxes Levied and Collected by the Centre but Distributed between the Centre and the States (Article 270): All taxes and duties listed in the Union List, excluding those specified in Articles 268, 269, and 269-A, fall into this category. Distribution of the net proceeds of these taxes is determined by the President based on recommendations from the Finance Commission.

E. Surcharges on Certain Taxes for Centre (Article 271): Parliament can impose surcharges on taxes mentioned in Articles 269 and 270. The income from these surcharges is exclusively allocated to the Centre, meaning states do not share in this revenue. Notably, surcharges cannot be applied to GST.

F. Taxes Levied and Collected and Retained by the States: These taxes, which exclusively belong to the states, are specified in the State List and include 18 items, such as land revenue, agricultural income taxes, excise duties on alcoholic beverages, electricity taxes, and several others related to local and state-level revenues.

Distribution of Non-Tax Revenues

1. The Centre

The major sources of non-tax revenues for the Centre include:

- Posts and telegraphs

- Railways

- Banking

- Broadcasting

- Coinage and currency

- Central public sector enterprises

- Escheat and lapse

- Other sources

2. The States

The principal sources of non-tax revenues for the states comprise:

- Irrigation

- Forests

- Fisheries

- State public sector enterprises

- Escheat and lapse

- Other sources

| Article | Levy | Collect | Assigned To | Example / Notes |

| 268 | Centre | States | States | Stamp duties on bills of exchange, promissory notes etc. (Not part of Consolidated Fund of India) |

| 269 | Centre | Centre | States | Taxes on inter-state trade and commerce (Not part of CFI) |

| 269A | Centre | Centre | Shared between Centre and States | GST on inter-state trade; Division of revenue is determined by Parliament on recommendation of GST Council; based on principle of supply |

| 270 | Centre | Centre | Shared between Centre and States | All taxes in Union List (except Articles 268, 269, 269A, surcharges under 271, and cesses); Distribution based on Finance Commission recommendation, prescribed by President |

| 271 | Centre | Centre | Centre | Surcharges on taxes under Articles 269 and 270; GST is exempted from surcharge |

| State taxes | State | State | State | Taxes exclusively for states (Total: 18) e.g., Land Revenue, Agricultural Income, Professional Tax |

Grants-in-Aid to the States

- In addition to tax revenue sharing, the Constitution provides for grants-in-aid to states from Central resources. These grants fall under two categories: statutory grants and discretionary grants.

Statutory Grants

- Article 275 grants Parliament the authority to provide financial assistance to states in need, which does not apply to all states, and different amounts may be allocated for different states. These grants are charged to the Consolidated Fund of India annually.

Additionally, the Constitution provides specific grants aimed at promoting the welfare of scheduled tribes or improving administration in scheduled areas within states, including Assam. Statutory grants under Article 275, both general and specific, are awarded based on the Finance Commission’s recommendations.

Discretionary Grants

- Article 282 permits both the Centre and the states to make grants for public purposes, even beyond their legislative competencies. These discretionary grants are not obligatory for the Centre to provide and allow the Centre to financially support states in meeting plan targets while also fostering coordination towards national initiatives.

Other Grants

- The Constitution also outlines a temporary provision for grants in lieu of export duties on jute and jute products for the states of Assam, Bihar, Orissa, and West Bengal. These grants were designated for ten years from the Constitution’s commencement, charged to the Consolidated Fund of India, and distributed based on the Finance Commission’s recommendations.

| Type of Grant | Constitutional Article | Key Features | Examples / Notes |

| Statutory Grants | Article 275 | – Given by Parliament to States needing financial assistance (not to all) – Two types: General & Specific (e.g., for tribal welfare) – Charged on Consolidated Fund of India – Given on recommendation of Finance Commission | Example: Grants to promote the welfare of Scheduled Tribes |

| Discretionary Grants | Article 282 | – Both Centre and States empowered to give grants for any public purpose – Discretionary in nature – Not necessarily based on Finance Commission – Can be given for temporary needs | Example: Grants in lieu of export duties on jute to Assam, Bihar, West Bengal, and Orissa |

| Other Grants | – | – May include temporary or situational grants – Often tied to specific circumstances or policy decisions – May still be charged on Consolidated Fund and follow FC recommendations | Often used for transitional arrangements or to address regional imbalances |

Goods and Services Tax Council

To ensure efficient management of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), cooperation between the Centre and the states is crucial. The 101st Amendment Act of 2016 established the Goods and Services Tax Council under Article 279-A.

The GST Council serves as a joint forum for the Centre and the states, making recommendations on various matters, including:

- Taxes, cesses, and surcharges that will be merged into GST.

- Goods and services that may be subjected to or exempted from GST.

- Model GST laws, principles of levy, apportionment for inter-state supplies, and the rules governing the location of supply.

- The threshold turnover limit for GST exemptions.

- GST rates, including floor rates and bands.

- Special rates during natural calamities to generate additional resources.

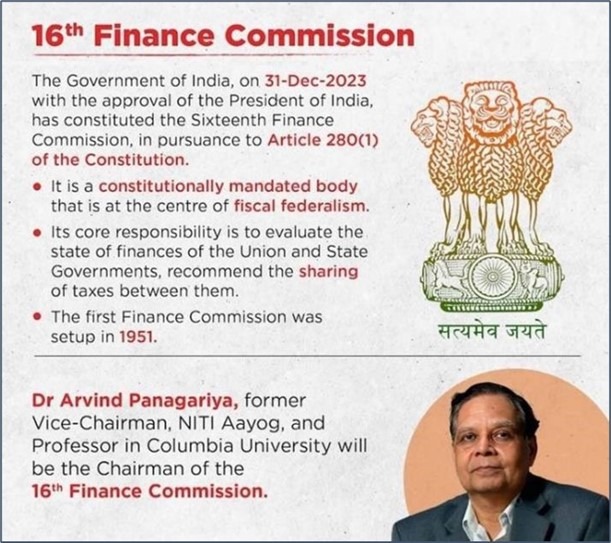

Finance Commission

- Article 280 of the Indian Constitution establishes the Finance Commission as a quasi-judicial body, constituted by the President every five years or earlier if necessary. The Finance Commission is tasked with making recommendations to the President on several key matters, including:

- The distribution of net tax proceeds to be shared between the Centre and the states, as well as the allocation of these proceeds among the states. The principles guiding grants-in-aid from the Centre to the states, funded by the Consolidated Fund of India.

- Measures to enhance the resources of a state’s Consolidated Fund to support panchayats and municipalities based on recommendations from the State Finance Commission.

- Any other financial matters referred to it by the President that are essential for sound fiscal management.

- Until 1960, the Finance Commission also proposed amounts to the states of Assam, Bihar, Orissa, and West Bengal to account for their share of revenue from export duties on jute and jute products.

- The Finance Commission plays a crucial role as the balancing wheel of fiscal federalism in India.

Protection of the States’ Interest

To safeguard the financial interests of states, the Constitution mandates that certain bills can only be introduced in Parliament with the President’s recommendation:

- Bills imposing or varying taxes or duties in which states have a stake.

- Bills that alter the definition of ‘agricultural income’ as per income tax laws.

- Bills affecting the principles governing the distribution of funds to states.

- Bills imposing surcharges on specified taxes or duties for Central purposes.

The term “tax or duty in which states are interested” refers to taxes or duties whose entire or partial net proceeds are assigned to a state or on which payments are made from the Consolidated Fund of India to any state.

The phrase ‘net proceeds’ refers to the revenue from a tax or duty after deducting collection costs. The Comptroller and Auditor-General of India is responsible for certifying the net proceeds of any tax or duty in a given area, and their certification is final.

Borrowing by the Centre and the States

The Constitution outlines specific provisions regarding the borrowing powers of the Centre and the states:

- The Central government can borrow funds both domestically and internationally, secured by the Consolidated Fund of India or through guarantees, but these must be within limits set by Parliament. As of now, no such legislation has been enacted by Parliament.

- State governments are allowed to borrow only within India and can secure their loans through the Consolidated Fund of the State, subject to limits established by the state legislature.

- The Central government has the authority to provide loans to states or offer guarantees for loans that states raise. Any funds required for these loans will be charged to the Consolidated Fund of India.

- A state is prohibited from raising loans without the Centre’s consent if it has any outstanding loans from the Centre or if the Centre has provided guarantees for those loans.

Inter-Governmental Tax Immunities

- In line with other federal constitutions, the Indian Constitution includes the principle of “immunity from mutual taxation” and contains the following provisions:

Exemption of Central Property from State Taxation

- Central government property is exempt from taxes imposed by state authorities, such as municipalities or district boards. However, Parliament can choose to lift this exemption. The term “property” encompasses all forms of assets, including lands, buildings, chattels, shares, debts, and both movable and immovable property. This property may serve sovereign purposes (e.g., military) or commercial uses.

Corporations or companies established by the Central government are not exempt from state or local taxation, as these entities are considered separate legal persons.

Exemption of State Property or Income from Central Taxation

- The property and income of states are exempt from Central taxation, regardless of whether they result from sovereign or commercial functions. However, the Centre can tax a state’s commercial operations if legislated by Parliament. Additionally, Parliament can designate certain trades or businesses as incidental to government functions, rendering them non-taxable.

Notably, local authorities within a state do not receive immunity from Central taxation. Similarly, the Centre can tax properties and incomes generated by corporations and companies owned by a state.

The Supreme Court, in an advisory opinion (1963), indicated that the immunity granted to states against Central taxation does not apply to customs duties or excise duties. Therefore, the Centre retains the right to impose customs duties on goods exported or imported by states, as well as excise duties on goods produced or manufactured by them.

Effects of Emergencies

- The financial relations between the Centre and the states are altered during emergencies as follows:

National Emergency

- During a national emergency declared under Article 352, the President has the authority to modify the constitutional distribution of revenues between the Centre and the states. This includes the power to reduce or cancel financial transfers (including both tax sharing and grants-in-aid) from the Centre to the states. These modifications remain in effect until the end of the financial year in which the emergency is lifted.

Financial Emergency

Under a financial emergency proclaimed pursuant to Article 360, the Centre can issue directions to the states to:

- Adhere to specified financial propriety standards.

- Reduce the salaries and allowances of all state employees.

- Reserve all money bills and other financial legislation for the President’s consideration.

Trends in Centre-State Relations

Until 1967, relations between the Centre and the states were relatively smooth, largely due to the dominance of a single party, the Congress, both at the Centre and in most states. However, the 1967 elections marked a significant shift when the Congress party was defeated in nine states, weakening its position at the national level. This political change ushered in a new phase characterized by heightened tensions in Centre-state relations. Non-Congress governments in various states began to oppose the increasing centralization of power and intervention by the Central government, advocating for greater state autonomy and more financial resources. This shift led to conflicts and tensions in their interactions.

Tension Areas in Centre-State Relations

Several issues have contributed to tensions and conflicts between the Centre and the states, including:

- The appointment and dismissal processes for governors.

- The perceived discriminatory and partisan role of governors.

- The imposition of President’s Rule for partisan purposes.

- The deployment of Central forces in states for maintaining law and order.

- The reservation of state bills for the President’s consideration.

- Discrimination in financial allocations to states.

- The role of the Planning Commission in approving state projects.

- Management of All-India Services (IAS, IPS, IFS).

- The use of electronic media for political gain.

- Appointment of inquiry commissions against chief ministers.

- Financial sharing between the Centre and states.

- Encroachment by the Centre on the State List.

These contentious issues have been under discussion since the mid-1960s, leading to various developments.

Administrative Reforms Commission

In 1966, the Central government established a six-member Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) chaired by Morarji Desai, followed by K. Hanumanthayya. One of its objectives was to examine Centre-state relations. To delve into the complex issues surrounding these relations, the ARC formed a study team led by M.C. Setalvad. Based on the team’s findings, the ARC prepared its report, submitted to the Central government in 1969, which presented 22 recommendations aimed at improving Centre-state relations. Notable recommendations included:

- Establishing an Inter-State Council under Article 263 of the Constitution.

- Appointing governors with extensive administrative experience and non-partisan attitudes.

- Delegating substantial powers to the states.

- Increasing financial resources transferred to the states to lessen their reliance on the Centre.

- Ensuring that Central armed forces are deployed in states only upon request.

Despite these recommendations, no actions were taken by the Central government to implement the suggestions of the ARC.

Rajamannar Committee

In 1969, the Tamil Nadu Government, led by the DMK, established a three-member committee chaired by Dr. P.V. Rajamannar to review Centre-state relations and recommend constitutional amendments aimed at enhancing state autonomy. The committee submitted its report in 1971, identifying several factors contributing to the prevailing unitary trends, or centralization, in the country, including:

- Certain constitutional provisions granting special powers to the Centre.

- One-party dominance at both the Centre and in the states.

- Inadequate fiscal resources for states, leading to dependency on Central financial assistance.

- The role of Central planning and the Planning Commission.

Key recommendations from the Rajamannar Committee included:

- The immediate establishment of an Inter-State Council.

- Making the Finance Commission a permanent body.

- Disbanding the Planning Commission and replacing it with a statutory body.

- Omission of Articles 356, 357, and 365, which govern President’s Rule.

- Removing the provision that allows the state ministry to hold office at the Governor’s pleasure.

- Transferring certain subjects from the Union List and the Concurrent List to the State List.

- Allocating residuary powers to the states.

- Abolishing all-India services (IAS, IPS, and IFS).

Despite the significance of these recommendations, the Central government ignored the Rajamannar Committee’s proposals.

Anandpur Sahib Resolution

In 1973, the Akali Dal adopted the Anandpur Sahib Resolution, which articulated both political and religious demands during a meeting in Punjab. The resolution called for a limitation of the Centre’s jurisdiction to matters of defense, foreign affairs, communications, and currency, proposing that all residuary powers should be vested in the states. It emphasized the need for the Constitution to be genuinely federal, ensuring equal authority and representation for all states at the Centre.

West Bengal Memorandum

In 1977, the West Bengal Government, led by the Communists, submitted a memorandum to the Central government proposing several changes to Centre-state relations. The memorandum recommended that:

- The term “union” in the Constitution should be replaced with “federal.”

- The Centre’s jurisdiction should be limited to defense, foreign affairs, currency, communications, and economic coordination.

- All other subjects, including residuary powers, should be allocated to the states.

- Articles 356, 357 (regarding President’s Rule), and 360 (financial emergency) should be repealed.

- States’ consent should be mandatory for the formation of new states or the reorganization of existing ones.

- Seventy-five percent of the total revenue collected by the Centre should be distributed to the states.

- The Rajya Sabha should have equal powers with the Lok Sabha.

- Only Central and state services should be maintained, abolishing all-India services.

Despite these proposals, the Central government did not act on the memorandum’s demands.

Sarkaria Commission

In 1983, the Central government established a three-member Sarkaria Commission on Centre-state relations, chaired by former Supreme Court judge R.S. Sarkaria. The Commission was tasked with reviewing the existing arrangements between the Centre and states and proposing necessary changes. Although initially given one year to complete its work, its term was extended four times, and the report was submitted in 1988.

The Commission did not advocate structural changes, believing that the existing constitutional arrangements were fundamentally sound. However, it emphasized the need for operational improvements and rejected calls to limit Central powers, arguing that a strong Centre is essential for maintaining national unity and integrity in the face of fragmentation. It noted that excessive centralization could lead to inefficiencies.

The Commission made 247 recommendations to enhance Centre-state relations, including:

- Establishing a permanent Inter-State Council, named the Inter-Governmental Council, under Article 263.

- Using Article 356 (President’s Rule) sparingly and only as a last resort.

- Strengthening the institution of All-India Services and creating additional services.

- Retaining residuary taxation powers with Parliament while allocating other residuary powers to the Concurrent List.

- Requiring the President to communicate reasons for withholding assent to state bills.

- Renaming and reconstituting the National Development Council as the National Economic and Development Council (NEDC).

- Reactivating zonal councils to promote federal spirit.

- Allowing the Centre to deploy armed forces without state consent, while still encouraging consultation.

- Consulting states before legislating on Concurrent List matters.

- Prescribing the consultation of the chief minister in the appointment of the state governor in the Constitution.

- Making net proceeds of corporation tax shareable with states.

- Ensuring the governor cannot dismiss the council of ministers if it holds a majority in the assembly.

- Preserving the governor’s five-year term barring compelling reasons for removal.

- Prohibiting commissions of inquiry against state ministers unless demanded by Parliament.

- Limiting surcharges on income tax by the Centre to specific purposes and durations.

- Maintaining the current division of responsibilities between the Finance Commission and the Planning Commission.

- Taking steps for the uniform implementation of the three-language formula.

- Maintaining centralized control over radio and television with operational decentralization.

- No changes to the Rajya Sabha’s role or the Centre’s power to reorganize states.

- Activating the commissioner for linguistic minorities.

The Central government has implemented 180 out of the 247 recommendations made by the Sarkaria Commission, with the establishment of the Inter-State Council in 1990 being one of the most significant actions taken.

Punchhi Commission

In April 2007, the Government of India established the Punchhi Commission, headed by former Chief Justice Madan Mohan Punchhi, to examine Centre-state relations in light of significant political and economic changes since the Sarkaria Commission’s last review over two decades prior. The Commission’s terms of reference included:

1. Review Existing Arrangements: The Commission was tasked with analyzing the current arrangements between the Centre and states based on the Constitution, including legislative and administrative relations, the role of governors, emergency provisions, financial relations, economic planning, and resource sharing, particularly concerning inter-state river water.

2. Consider Social and Economic Developments: In making recommendations, the Commission was expected to consider social and economic advancements over the years, especially in the last two decades, and to focus on good governance, national unity, and strategies for enhancing economic growth to combat poverty and illiteracy.

3. Key Areas of Focus: The Commission was to specifically evaluate:

- The Centre’s role during significant outbreaks of communal or caste violence.

- The Centre’s responsibilities in major projects like inter-linking rivers that require state support.

- Promoting effective devolution of powers to Panchayati Raj Institutions and Local Bodies.

- Independent planning and budgeting at the district level.

- Linking Central assistance to state performance.

- Strategies for positive discrimination in favor of backward states.

- The impact of Finance Commission recommendations on state finances.

- The relevance of separate production and sales taxes following the introduction of the VAT regime.

- The need to facilitate inter-state trade for a unified domestic market.

- The necessity of a Central Law Enforcement Agency for serious interstate or international crimes affecting national security.

- The feasibility of legislation under Article 355 for deploying Central forces in states as needed.

The Commission submitted its comprehensive report in April 2010, spanning 1,456 pages and seven volumes. In preparing its conclusions, the Commission drew extensively from the findings of the Sarkaria Commission, the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution, and the Second Administrative Reforms Commission. However, the Punchhi Commission diverged from several recommendations made by the Sarkaria Commission in various areas.

The final conclusion of the Commission emphasized that “cooperative federalism” would be central to preserving India’s unity, integrity, and future social and economic development, suggesting that these principles should guide Indian polity and governance moving forward.

Punchhi Commission Recommendations

The Punchhi Commission, established to address Centre-state relations, made over 310 recommendations upon examining various issues. Here are some key recommendations:

- Legislative Cooperation: Prior to introducing legislation on Concurrent List subjects in Parliament, the Union and states should reach a broad agreement for effective implementation.

- Restraint on Parliamentary Supremacy: The Centre should exercise caution in asserting Parliamentary supremacy in state matters. More flexibility for states regarding subjects in the State List and Concurrent List is essential for improving relations.

- Necessity of Central Jurisdiction: The Centre should only legislate on subjects in shared jurisdiction when absolutely necessary for national uniformity.

- Inter-State Council: A continuing auditing role for the Inter-State Council should be established for managing concurrent or overlapping jurisdictions.

- Timely Decision on Bills: The six-month timeline in Article 201 for state legislatures to act on returned bills should apply equally to the President regarding his decision on state bills.

- Treaty Legislation: Parliament should create a law regarding treaty-making processes, ensuring they are consistent with India’s federal structure.

- Financial Implications of Treaties: Future Finance Commissions should consider the financial obligations arising from international treaties and agreements.

- Governorship Guidelines: The Centre should appoint governors following strict guidelines: they should be eminent individuals from outside the state, detached from local politics, and not recently active in politics.

- Fixed Tenure for Governors: Governors should have a fixed five-year term, with their removal from office not at the discretion of the Central government.

- Impeachment Procedure: The procedure for the impeachment of the President should similarly apply to governors.

- Governor’s Discretion: Article 163 should not grant governors general discretionary powers to act against the advice of their Council of Ministers, with discretion exercised only rationally and in good faith.

- Timely Decision on Assent: Governors should decide within six months whether to grant assent to bills passed by the state assembly.

- Guidelines for Chief Minister Appointments: Clear guidelines should dictate the Governor’s role in appointing a Chief Minister in a hung assembly, prioritizing the party or coalition with the most support.

- Majority Confirmation: Governors should require the Chief Minister to demonstrate a majority in the assembly before dismissing them.

- Prosecution of Ministers: Governors should have the right to permit prosecutions of state ministers against the Council’s advice if motivated by bias.

- Governor’s Roles: The dual role of governors as Chancellors of universities and in other statutory positions should cease, limiting their roles to constitutional provisions.

- Emergency Situations: In situations of external aggression or internal disturbances, all alternative measures under Article 355 should be exhausted before invoking Article 356, which should be strictly limited to restoring constitutional order.

- Guidelines for Article 356: Amendments are needed to clarify the use of Article 356 following the S.R. Bommai case, mitigating state concerns and enhancing Centre-state relations.

- Localized Emergencies: A constitutional framework should be developed for localized emergencies, allowing for Central intervention without fully resorting to Articles 352 and 356. This ensures state governance continues while providing specific mechanisms for Central response.

- Amendments to Article 263: The Commission proposed that Article 263 be amended to strengthen the Inter-State Council, making it a credible and effective mechanism for managing interstate and Centre-state differences.

- Zonal Councils: The Zonal Councils should convene at least twice yearly, with agendas suggested by the states to enhance coordination and harmonize policies on matters with interstate implications. The Inter-State Council Secretariat could also function as the Secretariat for the Zonal Councils.

- Empowered Committee of Finance Ministers: The successful experience of the Empowered Committee of Finance Ministers should be replicated in other sectors. A rotating forum of Chief Ministers should be formed to coordinate policies in key areas like energy, education, and health.

- New All-India Services: The creation of additional All-India Services in fields such as health, education, and engineering were recommended.

- Second Chamber Representation: The Commission suggested removing factors that inhibit the effective functioning of the Rajya Sabha as a representative forum for states. Adjustments may require constitutional amendments to allow equal representation for states regardless of population size.

- Devolution of Powers: Clear constitutional definitions for devolving powers to local bodies as self-governing institutions should be established through amendments.

- Cost Sharing in Central Legislation: Future Central laws affecting states should include provisions for cost sharing, similar to the Right to Education (RTE) Act, and existing laws should be amended accordingly to provide for this.

- Royalty Rates on Major Minerals: Royalty rates should be revised every three years, with states compensated for any delays beyond this period.

- Removal of Profession Tax Ceiling: The current ceiling on profession tax should be eliminated through a constitutional amendment.

- Revenue Generation from Article 268 Taxes: A renewed examination of potential revenue from taxes under Article 268 should be conducted, either by the next Finance Commission or by appointing an expert committee.

- Fiscal Legislation Accountability: All fiscal laws should mandate annual assessments by an independent body, with the findings presented to both Houses of Parliament and state legislatures.

- Finance Commission Terms of Reference: The considerations in the Finance Commission’s Terms of Reference should be balanced between the Centre and the states, with an effective mechanism ensuring state involvement in finalizing these terms.

- Review of Cesses and Surcharges: The Central government should evaluate all existing cesses and surcharges to reduce their share in overall tax revenue.

- Plan vs. Non-Plan Expenditure: An expert committee may be appointed to explore the distinction between plan and non-plan expenditures, given their interconnections.

- Better Coordination Between Finance and Planning Commissions: Improved synchronization between the Finance Commission and the Planning Commission, especially regarding their respective cycles, is essential for better coordination.

- Institutional Support for Finance Commission: The Finance Commission division in the Ministry of Finance should become a full-fledged department, acting as a permanent secretariat for the Finance Commissions.

- Role of Planning Commission: The Planning Commission should focus on coordination rather than micromanaging sectoral plans at both the Centre and state levels.

- Establishment of an Inter-State Trade and Commerce Commission: A new commission under Article 307 should be created with both advisory and executive authority, making decisions binding on the Centre and states. Aggrieved parties could appeal to the Supreme Court regarding the Commission’s decisions.

The Punchhi Commission’s report was shared with various stakeholders, including State Governments and Union Ministries, for their feedback on the recommendations. These comments are currently being considered by the Inter-State Council.

The Central government implemented many of these recommendations, notably establishing the Inter-State Council in 1990.

Important Committees on Centre–State Relations

Committees by Centre | Committees / Initiatives by States |

Administrative Reforms Commission | Rajamannar Committee (1969) – Tamil Nadu |

Sarkaria Commission (1983) | Anandpur Sahib Resolution (1973) – Punjab |

Punchhi Commission (2007) | West Bengal Memorandum (1977) |