Basic Structure of the Constitution

Emergence of the Basic Structure

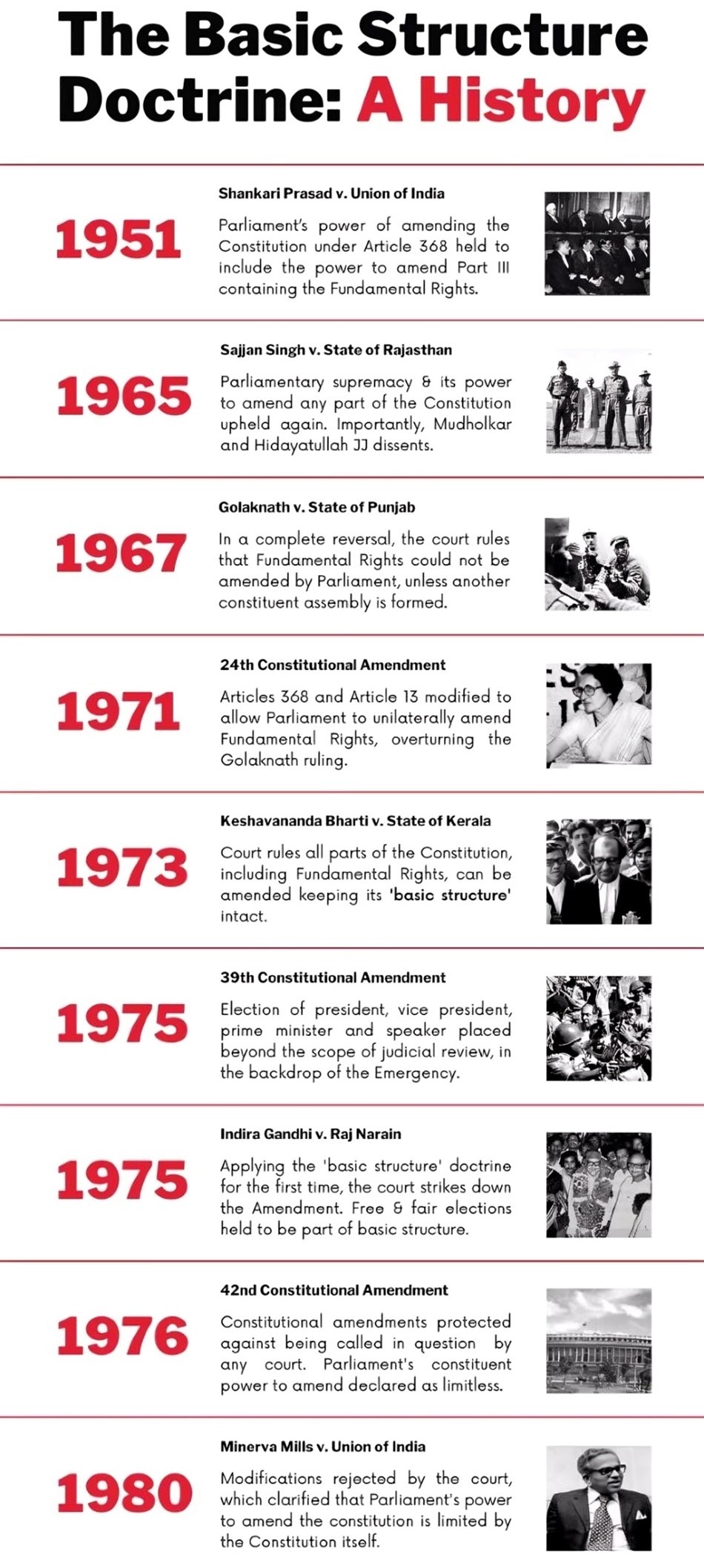

The issue of whether Fundamental Rights can be amended by Parliament under Article 368 was first addressed by the Supreme Court shortly after the Constitution came into effect. In the Shankari Prasad case (1951), the constitutional validity of the First Amendment Act (1951), which limited the right to property, was scrutinized. The Supreme Court concluded that the Parliament’s authority to amend the Constitution under Article 368 encompasses the ability to amend Fundamental Rights. The term ‘law’ in Article 13 pertains solely to ordinary legislation and excludes constitutional amendment acts (constituent laws). Therefore, Parliament can modify or eliminate any Fundamental Rights by enacting a constitutional amendment, and such laws will not be rendered void under Article 13.

However, this stance was reversed in the Golak Nath case (1967). Here, the constitutional validity of the Seventeenth Amendment Act (1964), which added certain state acts to the Ninth Schedule, was contested. The Supreme Court determined that Fundamental Rights hold a ‘transcendental and immutable’ status. Consequently, Parliament cannot modify or rescind any of these rights. According to this ruling, a constitutional amendment act is considered a law under Article 13 and would therefore be invalid if it infringes upon any Fundamental Rights.

In response to the Supreme Court’s decision in the Golak Nath case (1967), Parliament enacted the 24th Amendment Act (1971). This act amended Articles 13 and 368, affirming that Parliament possesses the authority to modify or eliminate any Fundamental Rights under Article 368, and clarifying that such an act will not be regarded as a law as defined by Article 13.

Nonetheless, in the Kesavananda Bharati case (1973), the Supreme Court overruled its previous judgment in the Golak Nath case (1967). It upheld the legitimacy of the 24th Amendment Act (1971) and affirmed that Parliament is authorized to amend Fundamental Rights. However, it established a new doctrine known as the ‘basic structure’ (or ‘basic features’) of the Constitution. This doctrine asserts that Parliament’s constituent power under Article 368 does not permit it to alter the basic structure of the Constitution, thereby preventing any abridgment or elimination of any Fundamental Right that constitutes a part of this basic structure.

The doctrine of basic structure was further confirmed and applied in the Indira Nehru Gandhi case (1975). In this instance, the Supreme Court invalidated a clause in the 39th Amendment Act (1975) that excluded election disputes involving the Prime Minister and the Speaker of the Lok Sabha from judicial review. The Court held that this provision transcended Parliament’s amending authority as it compromised the Constitution’s basic structure.

In response to the judiciary’s creation of the ‘basic structure’ doctrine, Parliament enacted the 42nd Amendment Act (1976), which modified Article 368 and stated that there are no constraints on Parliament’s constituent power, and no amendment could be challenged in any court for any reason, including the violation of Fundamental Rights.

However, in the Minerva Mills case (1980), the Supreme Court struck down this provision as it excluded judicial review, deemed a ‘basic feature’ of the Constitution. The Court applied the doctrine of ‘basic structure’ concerning Article 368, asserting that although the Constitution grants Parliament a limited amending power, it cannot extend this power to an absolute one. It noted that a limited amending power is integral to the Constitution’s basic features, thus these limitations cannot be eradicated. Essentially, Parliament cannot enhance its amending authority under Article 368 to a point where it can repeal or dismantle the Constitution or compromise its fundamental attributes. The holder of limited power cannot, through the exercise of that power, transform it into unlimited power.

In the subsequent Waman Rao case (1981), the Supreme Court reiterated its commitment to the doctrine of ‘basic structure,’ clarifying that it applies to constitutional amendments enacted after April 24, 1973, which is the date of the Kesavananda Bharati judgment.

Elements of the Basic Structure

The current understanding is that Parliament, under Article 368, has the authority to amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights, as long as it does not alter the ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution. However, the Supreme Court has yet to provide a definitive explanation or clarification regarding what constitutes the ‘basic structure.’ From various judgments, the following have been identified as ‘basic features’ or elements of the basic structure of the Constitution:

- Supremacy of the Constitution

- Sovereign, Democratic, and Republican Nature of the Indian Polity

- Secular Character of the Constitution

- Separation of Powers among the Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary

- Federal Character of the Constitution

- Unity and Integrity of the Nation

- Welfare State (Socio-Economic Justice)

- Judicial Review

- Freedom and Dignity of the Individual

- Parliamentary System

- Rule of Law

- Harmony and Balancebetween Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles

- Principle of Equality

- Free and Fair Elections

- Independence of the Judiciary

- Limited Power of Parliament to Amend the Constitution

- Effective Access to Justice

- Principles (or Essence) Underlying Fundamental Rights

- Powers of the Supreme Courtunder Articles 32, 136, 141, and 142

- Powers of the High Courtsunder Articles 226 and 227

These elements serve to uphold the integrity and foundational principles of the Constitution, ensuring the protection of individual rights and the framework of governance within the country.

This table outlines the progression and key rulings of various landmark cases that have contributed to the definition and understanding of the basic structure of the Indian Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court.

Sl. No. | Name of the Case (Year) | Elements of the Basic Structure (As Declared by the Supreme Court) |

1 | Kesavananda Bharati case (1973) (popularly known as the Fundamental Rights Case) | 1. Supremacy of the Constitution |

2 | Indira Nehru Gandhi case (1975) (popularly known as the Election Case) | 1. India as a sovereign democratic republic |

3 | Minerva Mills case (1980) | 1. Limited power of Parliament to amend the Constitution |

4 | Central Coal Fields Ltd. Case (1980) | Effective access to justice |

5 | Bhim Singhji Case (1981) | Welfare State (Socio-Economic Justice) |

6 | S.P. Sampath Kumar Case (1987) | 1. Rule of law |

7 | P. Sambamurthy Case (1987) | 1. Rule of law |

8 | Delhi Judicial Service Association Case (1991) | Powers of the Supreme Court under Articles 32, 136, 141, and 142 |

9 | Indra Sawhney Case (1992) (popularly known as the Mandal Case) | Rule of law |

10 | Kumar Padma Prasad Case (1992) | Independence of the Judiciary |

11 | Kihoto Hollohon Case (1993) (popularly known as the Defection Case) | 1. Free and fair elections |

12 | Raghunath Rao Case (1993) | 1. Principle of equality |

13 | S.R. Bommai Case (1994) | 1. Federalism |

14 | L. Chandra Kumar Case (1997) | Powers of the High Courts under Articles 226 and 227 |

15 | Indra Sawhney II Case (2000) | Principle of equality |

16 | All India Judge’s Association Case (2002) | Independent judicial system |

17 | Kuldip Nayar Case (2006) | 1. Democracy |

18 | M. Nagaraj Case (2006) | Principle of equality |

19 | I.R. Coelho Case (2007) (popularly known as IX Schedule Case) | 1. Rule of law |

20 | Ram Jethmalani Case (2011) | Powers of the Supreme Court under Article 32 |

21 | Namit Sharma Case (2013) | Freedom and dignity of the individual |

22 | Madras Bar Association Case (2014) | 1. Judicial review |