NATIONAL INCOME AND GDP

NATIONAL INCOME AND GDP

National Income: A Key Economic Metric

National Income is a crucial indicator that reflects a nation’s economic health by measuring the total output of goods and services produced over a specific period. It provides insights into a country’s economic performance, productivity, and overall standard of living.

Importance of National Income:

1. Economic Performance: National income serves as a benchmark for assessing how well an economy is doing. Higher national income typically indicates stronger economic activity.

2. Standard of Living: It offers a glimpse into the general living standards of a population. An increase in national income often correlates with improved quality of life.

3. Policy Making and Planning: National income data is vital for governments in making informed decisions regarding economic policies, budget allocations, and resource management.

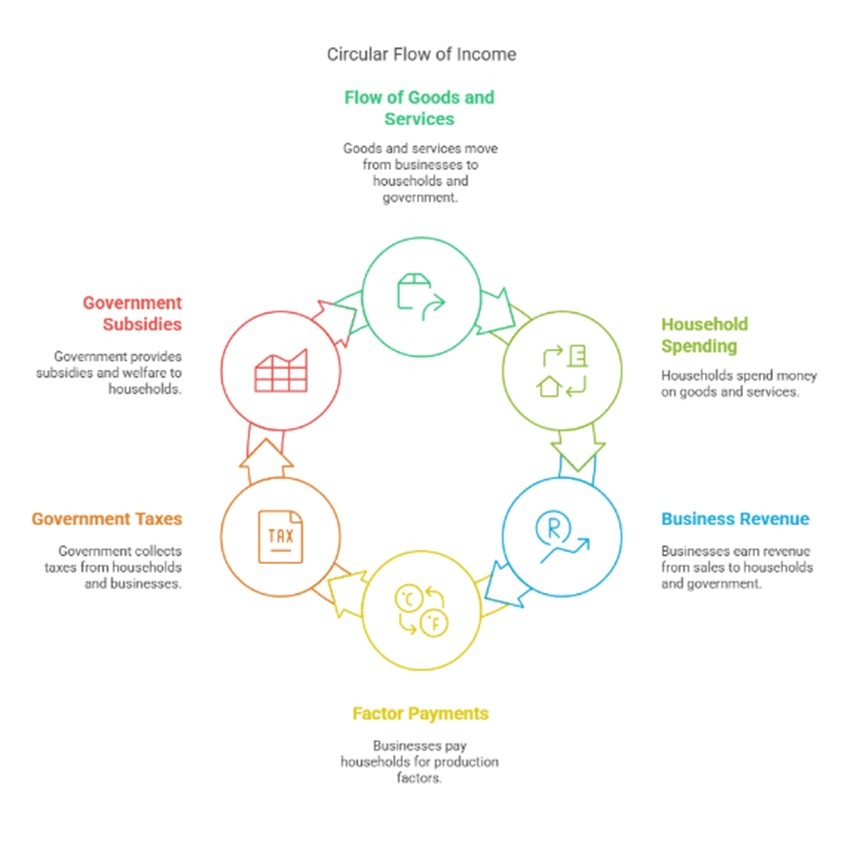

Circular Flow of Income

The circular flow of income is a fundamental concept in economics that demonstrates how money and resources move through an economy. It provides a simplified model of complex economic interactions among various sectors, including households, businesses, government, and the rest of the world.

Key Components of the Circular Flow of Income:

1. Households

- Role: Households are the primary consumers in the economy. They provide the factors of production (land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship) to businesses.

- Income Generation: In exchange for providing these resources, households receive income in the form of wages, rent, interest, and profits.

- Consumption: They use this income to buy goods and services produced by businesses, which directly drives demand in the economy.

2. Businesses

- Production: Businesses utilize the factors of production from households to create goods and services. This production is essential for satisfying consumer needs.

- Sales and Income: Businesses sell their products to households and other businesses. The revenue earned from these sales is used to pay wages, rent, and dividends, creating a cycle of income distribution.

3. Government

- Taxation: The government collects taxes from both households and businesses. This revenue is crucial for funding public services and infrastructure.

- Public Goods and Services: Governments use tax revenues to provide essential services like education, healthcare, transportation, and social welfare programs, benefiting the population and contributing to overall economic stability.

4. Rest of the World

- International Trade: This component encompasses all economic transactions with foreign countries. It includes imports (goods and services purchased from abroad) and exports (goods and services sold to other countries).

- Impact on the Economy: The rest of the world influences the domestic economy by providing access to foreign markets for businesses and creating additional consumer choices for households.

Significance of the Circular Flow of Income:

1. Interconnectedness of Sectors:

- It highlights the interdependence between households, businesses, the government, and the foreign sector. A change in one sector directly impacts the others, creating a dynamic economic environment.

2. Understanding Money Movement:

- The model is essential for understanding how money circulates in an economy, demonstrating that all economic activity revolves around this movement of resources and income.

3. Ripple Effects of Economic Changes:

- The circular flow illustrates how changes—such as a rise in government spending, a boom in exports, or a change in consumer habits—can affect the entire economy, influencing growth, employment, and overall economic health.

Limitations of the Circular Flow of Income:

1. Assumption of Perfect Competition:

- The model assumes that all markets operate under perfect competition, which is rarely the case in real-world economies. Market imperfections can significantly alter the flow dynamics.

2. Exclusion of Financial Institutions:

- Financial institutions, such as banks, play a crucial role in the economy by providing credit and facilitating transactions. The circular flow model does not integrate their influence, limiting its comprehensiveness.

3. Omission of Aggregate Demand and Supply:

- The model does not explicitly consider aggregate demand and supply, which are critical for understanding broader economic fluctuations and policies.

The circular flow of income is a foundational concept that helps to clarify the interactions within an economy. While it simplifies complex relationships, it effectively provides insights into how different sectors work together, illustrating the movement of money and resources. Despite its limitations, it serves as a valuable framework for understanding economic principles and the impact of various factors on overall economic health.

TYPES OF CIRCULAR FLOW OF INCOME

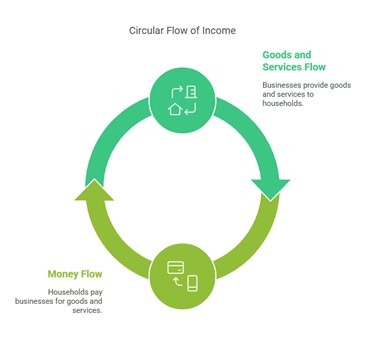

1. Circular Flow of Income in a Two-Sector Economy

The two-sector model is the simplest representation of the circular flow of income. It illustrates how money and resources circulate between two core economic agents:

1. Households

2. Firms

This basic framework lays the groundwork for understanding how income is generated and spent in an economy.

1. Key Components of the Two-Sector Model

A. Households: Resource Owners and Consumers

Households own all the factors of production—namely:

- Labor

- Land

- Capital

- Entrepreneurial skills

They supply these resources to firms in exchange for income.

Household Activities

Provide factor services to firms (labor, capital, etc.)

Receive income:

- Wages (for labor)

- Rent (for land)

- Interest (for capital)

- Profit (for entrepreneurship)

- Use income entirely for consumption of goods and services produced by firms.

B. Firms: Producers and Employers

Firms hire resources from households and use them to produce goods and services.

Firm Activities:

- Employ factors of production

- Pay factor incomes to households

- Produce goods and services

- Sell output to households

- Receive revenue from households through consumption

2. Flows in the Two-Sector Model

The model includes two types of flows:

A. Real Flows (Physical Flows):

From Households to Firms:

- Factors of production (labor, land, capital, entrepreneurship)

From Firms to Households:

- Goods and services (produced using the supplied resources)

B. Money Flows (Financial Flows):

From Firms to Households:

- Factor payments (wages, rent, interest, profit)

From Households to Firms:

- Consumption expenditure (purchase of goods and services)

These flows form a closed loop, creating a circular pattern of income and expenditure.

3. Continuous Circular Nature

The circular flow illustrates how income and output circulate in the economy:

1. Households supply resources → Firms use them to produce goods.

2. Firms pay incomes → Wages, rent, interest, and profits flow to households.

3. Households spend their income → Firms earn revenue from selling goods.

4. Firms reinvest this revenue → Pay for more resources from households.

This creates a self-sustaining loop, as long as households continue to spend and firms continue to produce.

4. Assumptions of the Two-Sector Model

To simplify analysis, several assumptions are made:

1. Closed Economy

- No interaction with foreign countries.

- No exports or imports.

2. No Government

- No taxes or government spending.

- No regulation or public services.

3. No Savings or Investment

- Households spend all their income on consumption.

- Firms use all their revenue to pay for factor services.

- No banking or financial institutions are included.

4. Perfect Competition

- Households and firms are price takers.

- No single actor can influence prices in the markets.

5. Diagrammatic Representation

A simplified two-sector circular flow can be illustrated with two concentric loops:

Outer Loop (Real Flow):

- Goods and Services: Firms → Households

- Factors of Production: Households → Firms

Inner Loop (Monetary Flow):

- Consumption Expenditure: Households → Firms

- Factor Payments: Firms → Households

6. Limitations of the Two-Sector Model

While useful as an introductory model, it is highly idealized and does not reflect the complexity of modern economies.

- No role for savings or investment

- Ignores government intervention

- Excludes international trade

- Doesn’t account for financial markets

- Assumes full income spending and no leakages

Thus, this model serves as a foundation, which is expanded in three-sector and four-sector models to reflect more realistic economic scenarios.

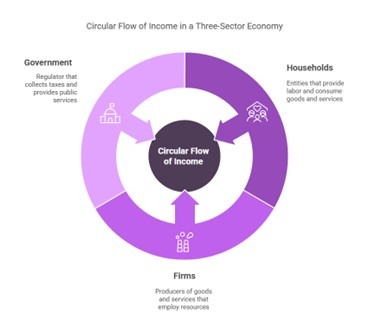

2. The Circular Flow of Income in a Three-Sector Economy

In macroeconomics, the circular flow of income is a model that illustrates the movement of money, resources, and goods and services in an economy. In a three-sector model, the primary actors are:

- Households

- Firms

- Government

This model builds upon the two-sector economy (households and firms) by adding the government, thereby making it more realistic and aligned with actual modern economies.

1. Households: The Factor Providers and Consumers

Households are the owners of the factors of production: land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship. They play a dual role in the economy:

A. Supplying Factors of Production:

- Households sell their labor, lend capital, allow the use of their land, and engage in entrepreneurial activities.

- These resources are purchased by firms to produce goods and services.

B. Receiving Factor Income:

In exchange for their resources, households receive income in various forms:

- Wages for labor

- Rent for land

- Interest for capital

- Profit for entrepreneurship

This income forms the basis of their purchasing power.

C. Consuming Goods and Services:

- Households use their income to buy goods and services from firms. This spending is called consumption expenditure, which is a key driver of demand in the economy.

D. Paying Taxes:

A portion of household income is taxed by the government.

- These may be direct taxes (income tax) or indirect taxes (GST/VAT on purchases).

- Taxes are a leakage from the circular flow—they reduce household consumption potential but fund government activities.

2. Firms: The Producers of Goods and Services

Firms are the productive units in the economy. Their primary role is to combine factors of production to produce goods and services.

A. Hiring Factors of Production:

- Firms demand labor, capital, land, and entrepreneurship from households.

- They pay households for these services through factor incomes.

B. Producing Output:

- Using the inputs, firms manufacture goods and services, which are then sold in the market.

- The scale and efficiency of this production affect economic growth and employment.

C. Selling to Households and Government:

Firms earn revenue by selling:

- Consumer goods to households

- Goods and services to the government for public use or investment (like construction, defense, public transport)

D. Paying Taxes:

Firms also pay taxes to the government, including:

- Corporate taxes

- Production taxes

- Sales taxes

Like household taxes, these are leakages from the circular flow but essential for funding public expenditure.

3. Government: The Regulator and Redistributor

The government plays a crucial role in influencing and stabilizing the economy. It interacts with both households and firms in multiple ways.

A. Collecting Taxes:

The government levies taxes on both:

- Households (income tax, consumption tax)

- Firms (corporate tax, GST, excise duty)

These tax collections are used for public spending, but they temporarily withdraw money from the flow, reducing consumption and investment.

B. Spending on Goods and Services:

The government spends tax revenue (and borrowed funds) on:

- Public goods (roads, schools, hospitals)

- Services (law enforcement, sanitation, defense)

This spending injects money back into the economy by increasing demand for goods and services produced by firms.

C. Providing Transfer Payments:

The government also redistributes income through transfer payments, such as:

- Unemployment benefits

- Pensions

- Subsidies

- Welfare payments

These are non-reciprocal payments (no goods or services are exchanged), aimed at supporting low-income groups, boosting consumption, and reducing inequality.

D. Borrowing:

If government spending exceeds its revenue (deficit), it borrows from:

- Domestic financial markets (e.g., issuing bonds)

- Foreign lenders

This borrowing ensures that government expenditure continues, keeping the flow active even during revenue shortfalls.

4. Flows in the Circular Model

A. Real Flows (Physical Flows):

These are the tangible movements of resources and goods:

- Households provide labor, land, capital to firms

- Firms provide goods and services to households and the government

B. Money Flows (Financial Flows):

These are the monetary payments associated with real flows:

- Firms pay wages, rent, interest, profits to households

- Households spend income on goods and services

- Taxes flow to the government

- Government injects money through spending and transfers

Both flows move simultaneously and continuously, ensuring the economy remains active and dynamic.

5. Injections and Leakages

The model includes two important concepts—injections and leakages—which help understand the balance and growth of the economy.

A. Leakages (Withdrawals from the Flow):

Leakages are reductions in the spending cycle, which slow down economic activity. They include:

1. Taxes (T): Collected by the government

2. Savings (S): Income not spent on consumption, stored in banks

3. Imports (M): Money spent on foreign goods/services

Leakages represent money that is not immediately re-spent in the domestic economy.

B. Injections (Additions to the Flow):

Injections are additions to the spending cycle, boosting economic activity. They include:

1. Government Spending (G): On infrastructure, services, etc.

2. Investment (I): Firms invest in capital goods, research, expansion

3. Exports (X): Foreign spending on domestic goods and services.

Injections increase demand and help maintain or increase the income flow.

6. Circular Nature of the Economy

The beauty of the model lies in its cyclical nature:

- Income flows from firms to households (as wages, rent, etc.)

- Households spend on goods and services, which returns income to firms

- Taxes move to the government, which uses it to spend on goods and services or transfer money back to households

- This re-circulation of money maintains economic activity

A balance between injections and leakages ensures that the circular flow is stable. If injections exceed leakages, the economy expands (growth); if leakages exceed injections, the economy contracts (recession).

Summary Table: Roles in the Circular Flow

Actor | Provides | Receives | Interaction With Other Sectors |

Households | Factors of production | Factor income, transfers | Sell to firms; pay taxes; consume |

Firms | Goods and services | Revenue from sales, subsidies | Hire from households; sell to govt |

Government | Public services, transfers | Taxes, borrowing | Spends on firms; transfers to people |

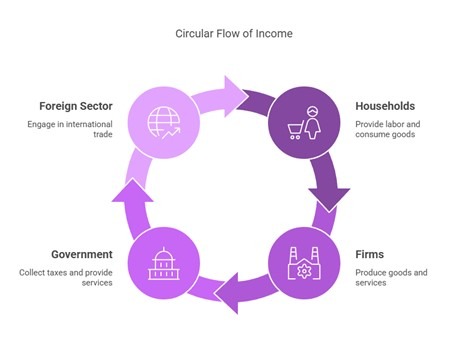

3. Circular Flow of Income in a Four-Sector Economy

The four-sector model of the circular flow of income provides a more complete and realistic view of a modern open economy. It includes:

1. Households

2. Firms

3. Government

4. Foreign Sector

This model captures the internal economic interactions and also external trade through imports and exports. The continuous flow of goods, services, resources, and money keeps the economy functioning efficiently.

1. Households: Providers and Consumers

Households play a dual role in the economy. They are both resource suppliers and consumers.

Functions:

Provide Factors of Production:

- Households offer labor, land, capital, and entrepreneurial skills to firms in exchange for income.

Earn Factor Incomes:

- Wages (for labor)

- Rent (for land)

- Interest (for capital)

- Profits (for entrepreneurship)

Consumption Expenditure:

- Households use their income to purchase goods and services from firms.

Pay Taxes:

- Taxes are paid to the government out of their incomes (direct taxes) and through purchases (indirect taxes).

Save a Portion of Income:

- Income not spent is saved, usually through financial institutions. Savings represent a leakage from the flow of income.

2. Firms: Producers and Income Distributors

Firms are responsible for the production of goods and services using resources provided by households.

Functions:

Employ Factors of Production:

- Firms hire labor, rent land, borrow capital, and utilize entrepreneurship to produce goods and services.

Pay Factor Incomes:

- Wages, rent, interest, and profits are paid to households as compensation for resource use.

Produce and Sell Output:

- Firms sell their output to:

- Households (consumption goods)

- Government (public procurement)

- Foreign Sector (exports)

- Firms sell their output to:

Investment:

- Firms invest in machinery, infrastructure, and research, adding to the productive capacity of the economy (an injection).

Pay Taxes:

- Taxes on profits, production, and sales are paid to the government.

3. Government: Regulator and Redistributor

The government plays an active role in economic stabilization, income redistribution, and resource allocation.

Functions:

Tax Collection:

- Taxes are collected from:

- Households (e.g., income tax)

- Firms (e.g., corporate tax, excise duties)

- Taxes are collected from:

Government Spending:

- Revenue is used to provide public goods and services, such as infrastructure, education, health, and defense.

- This spending goes to:

- Firms (purchase of goods and services)

- Households (wages for public employees, pensions, welfare transfers)

Transfer Payments:

- Government makes non-reciprocal payments:

- Social security

- Unemployment benefits

- Subsidies to firms

- Government makes non-reciprocal payments:

Borrowing:

- When expenditures exceed revenues, the government borrows domestically or from international institutions, adding funds into the economic flow.

4. Foreign Sector: Trade and Global Linkages

The foreign sector connects the domestic economy to the rest of the world, enabling international trade and financial flows.

Functions:

Exports (X):

- Domestic firms sell goods and services abroad.

- Exports bring foreign money into the economy—an injection.

Imports (M):

- Domestic households, firms, or the government buy foreign goods and services.

- Imports involve spending money outside the domestic economy—a leakage.

Net Exports:

- The difference between exports and imports (X − M) affects the overall circular flow.

- If X > M → Net injection

- If M > X → Net leakage

- The difference between exports and imports (X − M) affects the overall circular flow.

5. Key Flows in the Four-Sector Model

A. Real Flows (Physical Movement):

- Factors of production: From households → firms

- Goods and services:

- From firms → households (consumption)

- From firms → government (public procurement)

- From firms → foreign buyers (exports)

B. Monetary Flows (Financial Movement):

- Income: From firms → households (factor payments)

- Consumption expenditure: From households → firms

- Taxes: From households and firms → government

- Government spending: From government → firms and households

- Investment: From firms → capital goods market

- Exports revenue: From foreign buyers → domestic firms

- Payment for imports: From domestic agents → foreign producers

6. Injections and Leakages

Understanding injections and leakages is essential for analyzing the equilibrium or disequilibrium in the economy.

A. Leakages (Withdrawals from the circular flow):

These reduce the flow of income and spending:

1. Savings (S): Income not spent by households

2. Taxes (T): Paid to the government

3. Imports (M): Money spent on foreign goods

B. Injections (Additions to the circular flow):

These boost economic activity:

1. Investment (I): Spending by firms on capital goods

2. Government Spending (G): Public expenditure on goods and services

3. Exports (X): Income from selling goods to foreign countries

Economic Equilibrium:

An economy is in equilibrium when:

Injections = Leakages

That is: I + G + X = S + T + M

If injections exceed leakages → economy expands (growth)

If leakages exceed injections → economy contracts (recession)

Summary Table of Sectoral Interactions

Sector | Provides | Receives | Role in Flow |

Households | Factors of production | Income, government transfers | Consume goods, pay taxes, save |

Firms | Goods and services | Revenue, subsidies | Produce, invest, pay wages, pay taxes |

Government | Public goods, services, transfers | Taxes, borrowed funds | Spends on public welfare and subsidies |

Foreign Sector | Imports | Export payments | Facilitates trade (exports/income, imports/leakage) |

Relationship between Factors of Production and Factors of Income

The interplay between factors of production and factors of income is a foundational concept in economics that helps explain how resources are transformed into goods and services and how the resulting income is distributed among the participants in an economy.

1. Factors of Production:

- Land: This encompasses all natural resources available for production, such as soil, minerals, forests, and water. Land is a primary input for agriculture, forestry, mining, and various other industries.

-

- Labor: Labor refers to the human effort expended in the production process. It includes not only physical tasks but also mental and creative contributions. Skilled labor, such as doctors and engineers, typically commands higher wages than unskilled labor.

-

- Capital: This includes the tools, machinery, buildings, and technology used to produce goods and services. Capital can be physical (like machinery) or financial (like money used for investment). The availability and quality of capital can greatly influence productivity and efficiency.

-

- Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurs are individuals who organize the other factors of production and take on the risks associated with starting and managing businesses. They innovate, create new products, and seek out markets, often driving economic growth.

2.Factors of Income:

- Rent: The payment made for the use of land and natural resources. Rent can be affected by factors such as location, quality, and demand for the land.

- Wages and Salaries: These are payments made to workers in exchange for their labor. The amount can vary based on skill level, industry standards, and labor laws.

- Interest: This is the payment made for the use of capital goods. Interest rates can fluctuate based on economic conditions and central bank policies, affecting both borrowers and lenders.

- Profit: The earnings that entrepreneurs receive from their successful business ventures after covering costs. Profit serves as a reward for taking risks and investing in production.

Key Relationship:

The fundamental relationship can be summarized as follows: what resources are employed in production (factors of production) influences what forms of income are generated (factors of income). For example, if a business effectively utilizes land and labor to develop a new product, it will generate revenue that subsequently translates into wages for employees, rent for the land, and profit for the business owners.

Factor of Production | Factor of Income |

Land | Rent: Payment for the use of land and natural resources. |

Labor | Wages and Salaries: Payment for the time and effort of workers. |

Capital | Interest: Payment for use of capital goods like machinery and equipment. |

Entrepreneurship | Profit: Earnings from successful business ventures. |

Importance of the Relationship

1. Analyzing Income Distribution:

- Understanding the relationship helps economists analyze how income is distributed across different sectors and demographics. For instance, capital-intensive industries may generate higher income for owners of capital compared to labor-intensive sectors. This analysis can reveal patterns of wealth concentration and help identify groups that may need assistance.

2. Formulating Economic Policies:

- Policymakers can leverage insights from this relationship to design economic policies that encourage fairness and growth. For example, adjusting tax rates can influence investments in certain sectors. The introduction of minimum wage laws can ensure that workers receive a fair income, directly impacting the distribution of income in society.

3. Understanding Economic Inequality:

- By investigating how income is allocated according to factors of production, we can better understand economic inequality. For example, if ownership of capital is concentrated in a small percentage of the population, wealth disparities can become entrenched. Analyzing these dynamics is crucial for implementing effective social policies to reduce inequality.

4. Making Informed Business Decisions:

- Businesses can use this relationship to assess their operational strategies. For instance, if the cost of labor is rising, a business might invest in automation (capital) to maintain profitability. Additionally, understanding the potential income generated from different factors helps companies make strategic decisions regarding investments, pricing, and resource allocation.

The relationship between factors of production and factors of income is a cornerstone of economic theory. It not only illustrates how resources are converted into wealth but also serves as a guiding framework for understanding economic interactions and the distribution of income. This understanding is essential for economists, policymakers, and business leaders alike, as it informs decisions that can lead to economic growth, stability, and equity.

By comprehending this relationship, stakeholders can make better-informed choices that enhance economic outcomes and contribute to societal well-being.

Key Terms in National Income Accounting

1. Total Monetary Value

What is Included

- The total monetary value represents the monetary worth of all goods and services produced within a country’s domestic territory during a specified period. This encapsulates both market transactions and value added through production.

What is Not Included

- Non-monetary goods and services, such as volunteer work and unpaid household labor, are excluded. These contributions, while valuable, do not have a quantifiable market price and are not reflected in monetary terms.

2. Final Goods and Services

What is Included

- Final goods and services are those that are produced for final consumption or investment. This category comprises:

- Durable Goods: Items that last for an extended period, like cars and appliances.

- Non-Durable Goods: Items consumed quickly, such as food and toiletries.

- Services: Intangible products provided, like healthcare, education, and entertainment.

- Final goods and services are those that are produced for final consumption or investment. This category comprises:

What is Not Included

- Intermediate goods and services, which are utilized as inputs in the production of other goods and services, are excluded. For instance, flour used in baking bread is an intermediate good and is not counted as part of total output.

3. Domestic Territory

What is Included

- Domestic territory refers to the geographical boundaries within which individuals, goods, and capital can flow freely. It includes:

- Territory within Political Frontiers: This encompasses all land and territorial waters under a nation’s jurisdiction.

- Vessels Operated by Residents: Ships and aircraft owned and operated by residents that travel between countries (e.g., Air India’s passenger planes).

- Fishing and Extraction Rights: Fishing vessels and oil rigs operated by residents in international waters where the country has exclusive rights (e.g., Indian fishing boats in the Indian Ocean).

- Domestic territory refers to the geographical boundaries within which individuals, goods, and capital can flow freely. It includes:

What is Not Included

- Territorial Enclaves: Areas such as embassies, which are considered part of foreign territories.

- International Organizations: Entities physically located in a country, like the United Nations, which do not form part of domestic territory.

- Foreign Military Establishments: Embassies and military bases located abroad do not count as part of a country’s domestic territory (e.g., Indian embassies in other countries).

4. Financial Year

What is Defined

- The financial year is a 12-month period used for accounting and reporting purposes. In India, it begins on April 1st and ends on March 31st of the following year. This time frame is essential for budgeting, financial reporting, and tax calculations.

Factor Cost vs Market Price

Understanding the distinction between factor cost and market price is essential for analysing production, pricing strategies, and economic dynamics.

1. Factor Cost

Definition: Factor cost refers to the total cost incurred by producers for utilizing the four primary factors of production: land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship.

Components:

Wages: Payments made to labourers for their efforts and time.

Rent: Costs associated with using land and natural resources.

Interest: Payments for the use of capital goods, such as machinery and equipment.

Profits: The earnings received by entrepreneurs after covering all costs.

Importance:

Production Costs: Factor cost serves as the baseline for determining how much it costs to produce goods and services.

Profitability: By understanding factor costs, businesses can strategize to minimize expenses and maximize profits.

2. Market Price

Definition: Market price is the price at which goods and services are offered for sale in the market. It reflects what consumers are willing to pay for these products.

Determining Factors

Supply and demand dynamics play a crucial role in setting market prices. High demand or limited supply can increase prices, whereas low demand or excess supply can decrease them.

Significance

Revenue Generation: Market price affects the revenue that businesses can generate from selling their products.

Consumer Behaviour: It indicates consumer willingness to pay and guides purchasing decisions.

Relationship Between Factor Cost and Market Price

The relationship can be expressed through the following equation:

Market Price (MP) = Factor Cost (FC) +Indirect Taxes – {Subsidies}

Components of the Equation:

Indirect Taxes (IT)

These are taxes imposed on the production and sale of goods and services, such as:

Excise Duty: Tax levied on the production of specific goods.

Customs Duty: Tax on goods imported into a country.

Sales Tax: Tax based on the sale of goods and services.

Impact: Indirect taxes increase the overall cost of production. As a result, they lead to higher market prices, which can affect consumer purchasing behaviour and overall demand.

Subsidies

Financial assistance provided by the government to support producers. They aim to lower production costs and encourage the production of essential goods and services.

Impact: By reducing the cost of production, subsidies effectively lower the market price, making goods more affordable for consumers. This can lead to increased demand for subsidized products.

National Income calculation

National income is a key indicator of a country’s economic performance, representing the total monetary value of all goods and services produced over a specified period, typically a financial year. Here’s a detailed breakdown of its components and significance.

Definition:

National Income: It is the financial reflection of all economic activities within a country during a defined period, typically measured annually. It accounts for the final outcome of these activities, captured in monetary terms.

Alternatively, national income can be viewed as the total income earned by residents from providing factor services (like labour and capital) to production units, both domestically and internationally.

Measurement Period:

National income is generally measured over a specific timeframe, typically aligned with the financial year, which in many countries runs from April 1st to March 31st.

Key Concepts:

Resident Concept:

This focuses on income earned by residents of a country, irrespective of where the production occurs. For instance, a citizen working abroad contributes to the national income of their home country.

Final Goods and Services:

National income considers only final goods produced for consumption. It excludes intermediate goods, which are utilized in the production of other goods, to avoid double counting.

Measurement through GDP:

National income is primarily measured using Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which captures the total value of final goods and services produced within a country’s borders during a specific period.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a fundamental economic measure reflecting the total monetary value of all final goods and services produced within a country’s domestic territory over a specific accounting year.

Key Points:

GDP Definition: It is the aggregate value produced in the economy, measured as the sum total of Gross Value Added (GVA) from all firms, sectors, and industries.

Significance of GDP:

GDP serves as a primary indicator of economic health and is used by policymakers and economists to gauge economic performance, compare productivity across nations, and guide investment decisions.

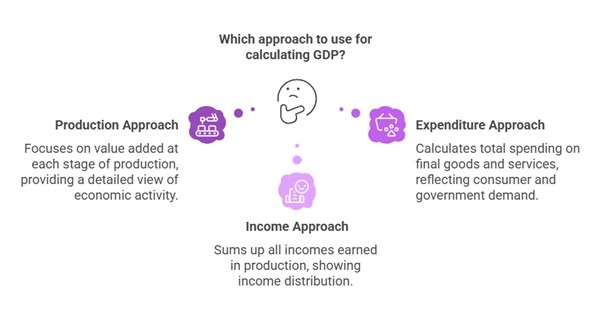

Calculation:

GDP can be computed using various approaches, including:

Production Approach: Summing up the value added at each stage of production.

Expenditure Approach: Calculating total spending on final goods and services.

Income Approach: Summing up all incomes earned in the production of goods and services.

key concepts under national income with examples:

1. Domestic/Economic Territory

Definition:

The economic territory of a country refers to the geographical area governed by its government, allowing the free circulation of individuals, goods, and capital.

Important Points:

- Foreign embassies within the country are not considered part of its economic territory.

- Domestic embassies abroad are considered part of the economic territory.

Inclusions in the Economic Territory:

1. Military establishments and embassies located in foreign countries.

- Example: The Indian embassy in the USA is considered part of India’s economic territory.

2. Ships, aircraft, and fishing vessels operated by residents, even when outside the country’s borders.

- Example: An Air India plane operating internationally contributes to India’s GDP.

2. Market Price (MP) vs. Factor Cost (FC)

Market Price (MP)

Definition:

Market price is the amount buyers are willing to pay and sellers are willing to accept for goods and services in an open market, influenced by supply and demand.

Example:

If the market price of a smartphone is $500, it includes:

- Production costs (wages, materials, rent, etc.).

- Indirect taxes such as GST/VAT.

Factor Cost (FC)

Definition:

Factor cost refers to the actual cost incurred in producing goods and services, excluding indirect taxes but including subsidies.

Formula:

Factor Cost=Market Price−Net Indirect Taxes

Where:

Net Indirect Taxes=Indirect Taxes−Subsidies

Example:

If a company produces furniture with a market price of $500, and it includes:

- Indirect taxes of $50,

- Government subsidy of $20,

Calculation:

Factor Cost=500−(50−20) =500−30 =470

3. Depreciation

Definition:

Depreciation represents the loss of value of an asset over time due to wear and tear, obsolescence, or aging.

Example:

A company purchases machinery for $100,000, and its value decreases by $10,000 per year due to wear and tear. This annual reduction of $10,000 is depreciation.

Importance:

- It reflects the true profitability of a business by considering the reduced value of assets over time.

4. Net Factor Income from Abroad (NFIA)

Definition:

The difference between income earned by a country’s residents from abroad and income earned by foreigners within the country.

Formula:

NFIA=Factor Income from Rest of the World−Factor Income to Rest of the World

Example:

- Indian companies earn $30 billion abroad.

- Foreign companies earn $20 billion in India.

Calculation:

NFIA=30−20=10 billion dollars

Impact:

A positive NFIA increases the Gross National Product (GNP).

5. Transfer Payments

Definition:

Monetary transactions made without expecting goods or services in return, usually for redistribution purposes.

Examples:

- Government welfare payments (e.g., pensions, unemployment benefits).

- Scholarships provided by the government.

- Foreign aid given to another country.

Key Point:

Transfer payments are not included in national income calculations because they do not reflect productive economic activity.

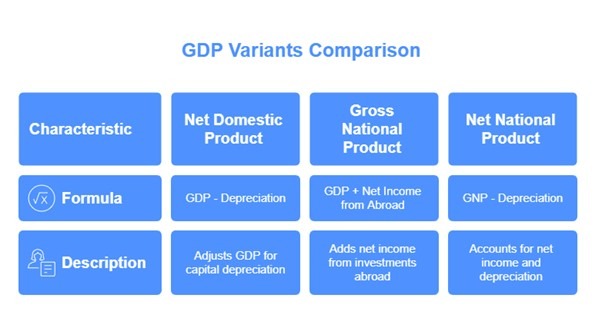

Variants of GDP:

Understanding the variants of GDP is crucial to comprehending national income measures:

Net Domestic Product (NDP):

Formula: NDP = GDP – Depreciation

It adjusts GDP by accounting for the depreciation of capital goods, which considers the wear and tear over time.

Gross National Product (GNP):

Formula: GNP = GDP + Net Income from Abroad

GNP adds net income earned by residents from investments abroad to GDP, reflecting the total economic output by residents.

Net National Product (NNP):

Formula: NNP = GNP – Depreciation

It accounts for both net income from abroad and the depreciation of capital, providing a clearer picture of the economy’s available resources.

1. Net Domestic Product (NDP)

Definition:

NDP is a measure of a nation’s economic output after accounting for depreciation of its capital assets. This measure is crucial because it provides a more accurate picture of the sustainable economic performance by indicating how much net output is available for consumption and investment.

Significance:

Understanding NDP helps policymakers and economists gauge the actual growth of an economy by factoring in the loss of value of capital goods. This adjustment is essential for long-term economic planning and assessing living standards over time.

NDP (Net Domestic Product):

NDP=GDP−Depreciation

- Example: Consider a country that produces various goods using machinery and equipment. If, at the end of a year, the economy generates a GDP of $1 trillion, but the machinery loses $200 billion in value over the same period (due to wear and tear), the NDP would be calculated as follows:

- [ NDP = GDP – {Depreciation} = 1 {trillion} – 200 {billion} = 800 {billion}] This $800 billion represents the net economic value generated after replacing depreciated capital, indicating resources available for investment or consumption.

2. Gross National Product (GNP)

Definition:

GNP measures the total economic output produced by the residents of a country regardless of their location—domestically or abroad. It captures the income earned by citizens on overseas investments and subtracts income earned by foreigners within the country.

Significance:

GNP is important for understanding a country’s overall economic performance and the global engagement of its citizens. It reflects the productive capacity and economic contributions of a nation’s residents, allowing for assessments of how much wealth is being created by the country’s citizens.

GNP (Gross National Product):

GNP=GDP+NFIA

- Example: If a country has a GDP of $1 trillion and its residents earn $200 billion from investments abroad while foreign residents earn $50 billion within the country, the GNP is determined as follows:

- [ GNP = GDP + {Net Factor Income from Abroad} = 1 {trillion} + (200 {billion} – 50 {billion}) = 1.15 {trillion}] This indicates that the economic contributions of the country’s citizens amount to $1.15 trillion globally.

3. Net National Product (NNP)

Definition:

NNP is the total economic output of a nation’s residents, adjusted for capital depreciation. This measure provides insight into the net economic productivity that can be sustained in the long term.

Significance:

NNP is crucial for assessing the welfare of current and future generations. It highlights whether an economy is sustainably utilizing its resources or depleting its capital stock.

Example:

Using the earlier GNP of $1.15 trillion, if annual depreciation is estimated to be $150 billion, then NNP is calculated as follows: [ NNP = GNP – {Depreciation} = 1.15 {trillion} – 150 {billion} = 1 {trillion}] This $1 trillion represents the real capacity for consumption and investment without diminishing capital assets over time.

4. National Disposable Income (NDI)

Definition:

NDI reflects the total income available to a nation for domestic consumption or savings after accounting for net transfers received from abroad. These transfers can include remittances or foreign aid.

Significance:

NDI is an essential indicator for understanding the economic well-being of a country’s residents. It provides insight into the amount of money available for spending and investment that can support economic growth and social welfare.

Example:

If the NNP is $1 trillion and the country receives $100 billion in foreign aid and remittances, NDI would be calculated as: [ NDI = NNP + {Other Current Transfers} = 1 {trillion} + 100 {billion} = 1.1 {trillion}] This amount of $1.1 trillion indicates the total financial resources available for households and governments to spend on goods and services.

1. Gross Domestic Product at Market Price (GDPMP)

Definition:

GDPMP represents the total market value of all finished goods and services produced within a country in a specific period, evaluated at prevailing market prices.

2. Gross Domestic Product at Factor Cost (GDPFC)

- Formula: [ {GDPFC} = {GDPMP} – {Indirect Taxes} + {Subsidies}]

- Definition: This measures the value of production based on the incomes earned by factors of production (labour and capital) before indirect taxes and after considering subsidies.

3. Net Domestic Product at Market Price (NDPMP)

- Formula: [{NDPMP} = {GDPMP} – {Depreciation}]

- Definition: NDPMP accounts for depreciation (the decrease in value of assets over time), providing a better insight into the net output of the economy.

4. Net Domestic Product at Factor Cost (NDPFC)

- Formula: [{NDPFC} = {NDPMP} – {Indirect Taxes} + {Subsidies}]

- Definition: This represents the net income available to factor owners, adjusted for taxes and subsidies.

5. Gross National Product at Market Price (GNPMP)

- Formula: [ {GNPMP} = {GDPMP} + {Net Factor Income from Abroad (NFIA)}]

- Definition: GNPMP includes all economic activities by residents of a country, regardless of where the activities take place. NFIA accounts for income earned by residents abroad minus income earned by foreigners in the domestic economy.

6. Gross National Product at Factor Cost (GNPFC)

- Formula: [ {GNPFC} = {GDPFC} + {NFIA}]

- Definition: Similar to GNPMP, but valued at factor cost. Adjustments for indirect taxes and subsidies are also applied here.

7. Net National Product at Market Price (NNPMP)

- Formula: [ {NNPMP} = {GNPMP} – {Depreciation}]

- Definition: NNPMP shows the net output based on national income after accounting for the reduction in the value of capital assets.

8. Net National Product at Factor Cost (NNPFC or National Income)

- Formula: [{NNPFC} = {NNPMP} – {Indirect Taxes} + {Subsidies}]

- Definition: NNPFC is considered equivalent to National Income and represents the actual income earned by the factors of production within the nation after accounting for depreciation and adjusting for taxes and subsidies.

Feature | GDP (Gross Domestic Product) | GNP (Gross National Product) | GNI (Gross National Income) |

Measurement | Total market value of final goods and services produced within a country’s borders. | Total market value of final goods and services produced by residents of a country, regardless of location. | Total income earned by residents of a country, including income earned from abroad. |

Focus | Production within a country’s borders. | Production by residents of a country. | Income received by residents of a country. |

Components | Consumption + Investment + Government Spending + Net Exports. | Consumption + Investment + Government Spending + Net Factor Income from Abroad. | GNI = GDP + Net Factor Income from Abroad. |

Uses | Measuring economic activity within a country. | Understanding the economic contribution of a country’s residents, regardless of where the production occurs. | Comparing the economic performance of different countries and assessing the overall income of residents. |

Limitations | Ignores income earned by foreign companies operating in the country. | Does not include income earned by residents abroad. | May not fully capture the well-being of all residents if significant income inequality exists. |

1. Private Income (PI)

Definition:

Private Income represents the total income received by the private sector, which includes individuals, businesses, and other private entities.

Components:

- Factor Income from Net Domestic Product: This includes wages, salaries, and profits earned by the private sector. It indicates the income generated through productive activities.

- National Debt Interest: This refers to the interest payments received by private entities from the government for national debt holdings.

- Net Factor Income from Abroad: It accounts for the difference between income earned by residents from overseas investments and income earned by foreigners in the domestic economy. A positive net income enhances total private income.

- Current Transfers from Government: These are transfers such as pensions, social security benefits, and scholarships that directly support households and contribute to their income.

- Other Net Transfers: This includes other forms of transfers from the rest of the world, excluding non-reciprocal gifts and foreign aid.

2. Personal Income (PI)

Definition:

Personal Income is derived from National Income and reflects the income attributed to households before taxation. It is crucial because it indicates the income available to individuals for consumption and saving.

Adjustment Components:

- Undistributed Profits: Profits retained by firms for reinvestment instead of being distributed to shareholders must be deducted from National Income as they do not directly benefit households.

- Corporate Tax: Since corporate taxes are not part of households’ income, they are subtracted from National Income to arrive at Personal Income.

- Net Interest Payments: While households earn interest on loans provided, they also incur interest on borrowed funds. Therefore, we calculate net interest payments (income received minus income paid) to determine the actual benefit to individuals.

- Transfer Payments: Positive contributions from government or firm transfers, like pensions and scholarships, need to be added back to NI to determine PI.

- Formula: [{Personal Income (PI)} = {National Income (NI)} – {Undistributed Profits (UP)} – {Net Interest Payments} – {Corporate Tax} + {Transfer Payments}]

3. Personal Disposable Income (PDI)

Definition:

PDI represents the income available to households for spending or saving after accounting for all mandatory payments.

Adjustment Components:

- Personal Tax Payments: This includes all taxes directly levied on individuals, such as income taxes, which reduce the disposable income available for personal use.

- Non-Tax Payments: Costs such as fees, fines, and other charges that are not classified as taxes but still represent a financial obligation for households.

- Formula: [{Personal Disposable Income (PDI)} = {Personal Income (PI)} – {Personal Tax Payments} – {Non-tax Payments}]

Overall Implications

Understanding these income concepts helps to analyze economic health and household financial capacity:

- Personal Incomeprovides a measure of total economic activity felt by individuals, while Personal Disposable Income reflects their real purchasing power after obligatory payments.

- Economic policies impacting taxes, government transfers, and corporate distributions will significantly affect both personal income and disposable income, influencing consumer behaviour and overall economic growth.

Nominal GDP and Real GDP

Nominal GDP

Nominal GDP represents the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within an economy, calculated using current market prices. It measures economic activity without adjusting for inflation, reflecting the market value at the time of measurement. Since nominal GDP is influenced by price changes, it may overstate or understate the true level of economic activity if inflation or deflation occurs.

The formula for Nominal GDP is: Nominal GDP = Current Price of Goods and Services × Quantity of Goods and Services

Importance of Nominal GDP:

- It reflects changes in both production levels and price fluctuations, helping in understanding short-term economic conditions.

- Provides a snapshot of an economy’s current financial health and helps in comparing economic performance across different time periods.

- Assists in analyzing trends in revenue and expenditure within the economy, which is crucial for budget planning and policy-making.

- It is useful for international comparisons, though it should be complemented with real GDP for a more accurate representation of growth.

Example Calculation: Consider an economy that manufactures 50 bicycles priced at ₹600 each and 100 scooters priced at ₹8,000 each. Nominal GDP = (50 bicycles × ₹600) + (100 scooters × ₹8,000) = ₹30,000 + ₹800,000 = ₹830,000

Real GDP

Real GDP measures the value of goods and services produced within an economy, adjusted for changes in price levels due to inflation. It provides an accurate depiction of economic growth by focusing solely on production volume, making it a better indicator of long-term economic performance.

Calculation of Real GDP: Real GDP is calculated by using prices from a selected base year, ensuring that inflation does not distort economic analysis. This adjustment allows policymakers and economists to compare economic output over time more accurately. The formula used is: Real GDP = Base Year Price × Quantity of Goods and Services

Significance of Real GDP:

- Offers a true measure of economic growth by eliminating the effects of inflation, making it ideal for long-term economic analysis.

- Provides a clear perspective on the actual expansion of an economy, aiding in the formulation of development policies.

- Enhances comparability of economic performance across years by focusing on real production growth rather than nominal increases.

- Helps in assessing improvements in living standards and economic welfare by reflecting purchasing power.

Example Calculation: Suppose in the base year, the price of bicycles was ₹500 each, and scooters were ₹5,000 each. If the economy produced 200 bicycles and 50 scooters in a subsequent year, the Real GDP calculation would be: Real GDP = (200 bicycles × ₹500) + (50 scooters × ₹5,000) = ₹100,000 + ₹250,000 = ₹400,000

Impact of Inflation on National Income Inflation significantly affects both the real and nominal values of national income. Understanding these effects is essential for designing effective economic policies to ensure stable growth.

Impact on Nominal Value:

- Increase: Inflation leads to an increase in the nominal value of national income. As prices rise, the total value of goods and services produced also increases, even if the production volume remains unchanged.

- Misleading Indicators: An increase in nominal GDP due to inflation can create a false perception of economic growth, as it does not necessarily imply an increase in actual output.

- Comparison Challenges: Comparing nominal values across periods with differing inflation rates can result in misinterpretation of economic progress.

Impact on Real Value:

- Decline in Purchasing Power: Inflation reduces the purchasing power of money, which means that higher nominal income does not necessarily translate into increased real income.

- Income Distribution Effects: Inflation may disproportionately affect different income groups, potentially worsening income inequality.

- Economic Uncertainty: Persistent inflation can create uncertainty for businesses and investors, discouraging long-term investments and hindering economic stability.

Policy Measures to Address Inflation

Monetary Policy

1. Interest Rate Adjustments:

- Central banks can increase interest rates to make borrowing more expensive and discourage spending, thereby reducing the money supply and inflationary pressures.

- Higher interest rates can lead to lower consumer spending and business investments, slowing economic activity and curbing inflation.

- Conversely, lowering interest rates can stimulate spending and investment but may risk higher inflation.

2. Reserve Requirements Adjustments:

- Central banks can increase reserve requirements for banks, requiring them to hold a larger portion of their deposits as reserves, which reduces the amount of money available for lending and spending.

- This measure directly impacts the money supply by limiting credit availability and ensuring financial stability.

- Lowering reserve requirements can have the opposite effect, increasing liquidity in the economy and potentially driving up inflation.

Fiscal Policy

1. Government Spending Adjustments:

- Governments can reduce spending, particularly on non-essential items, to decrease aggregate demand and inflationary pressures.

- Reduced government expenditure can slow down economic activity but may also affect public services and infrastructure development.

- Alternatively, increased government spending in critical areas can stimulate economic growth but might lead to higher inflation if not managed properly.

2. Taxation:

- Implementing progressive tax policies can help control inflation by reducing the disposable income of individuals with higher incomes, thereby decreasing aggregate demand.

- Higher taxes can lead to reduced consumer spending and lower inflationary pressures.

- However, excessive taxation may discourage investment and economic growth.

Supply-Side Policies

1. Promoting Competition:

- Government policies can encourage competition in key sectors to reduce market power and price manipulation by businesses.

- Enhanced competition leads to greater efficiency, lower prices, and improved consumer choice.

- Policies such as deregulation, anti-monopoly laws, and encouraging new market entrants can help achieve these goals.

2. Investing in Infrastructure:

- Investing in infrastructure can improve efficiency and productivity, leading to lower production costs and potentially reducing inflationary pressures.

- Better infrastructure facilitates smoother supply chains and reduces production bottlenecks, improving overall economic output.

- Long-term benefits include enhanced economic growth and competitiveness.

3. Trade Policies:

- Implementing trade policies that encourage imports and discourage exports can help increase the supply of goods and services in the domestic market, reducing inflationary pressures.

- Tariff reductions and trade agreements can enhance market competition and provide consumers with more affordable options.

- However, excessive reliance on imports may expose the economy to global market fluctuations.

Income and Price Controls

1. Price Controls:

- Direct government regulation of prices and wages can be implemented in exceptional circumstances to control inflation.

- Such controls can provide short-term relief but may lead to unintended consequences such as shortages and black markets.

- Gradual phasing out of price controls, combined with structural reforms, is often recommended.

2. Income Policies:

- Government agreements with businesses and labor unions to limit wage and price increases can help control inflation.

- Such agreements can ensure fair wage growth while maintaining economic stability.

- However, these policies can also restrict economic growth and flexibility if not carefully managed.

Comparative Analysis Between Real and Nominal GDP

Feature | Real GDP | Nominal GDP |

Definition | Measures the actual volume of goods and services produced after adjusting for inflation | Measures the market value of goods and services at current prices |

Focus | Production of goods and services | Market value and price levels |

Benefits | Tracks actual economic growth | Provides a current picture of the economy |

Limitations | Requires a base year and data adjustments | Can be misleading due to inflation |

Applications | Comparing economic performance across time and countries | Analyzing current economic activity and its relationship with inflation and interest rates |

GDP Deflator

- The GDP deflator (also known as the implicit price deflator) is a measure of inflation for the entire economy.

- It is calculated using the formula:

GDP Deflator = (Nominal GDP / Real GDP) × 100

- A higher GDP deflator indicates higher inflation, while a lower GDP deflator indicates lower inflation.

- The GDP deflator provides insight into the price level changes across the entire economy and helps policymakers make informed economic decisions.

- Unlike the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the GDP deflator covers all goods and services produced domestically rather than focusing only on a fixed basket of goods and services.

In simpler terms, the GDP deflator tells us how much prices have changed on average for all goods and services produced in an economy over a specific period.

Key Features of the GDP Deflator

1. Comprehensive Inflation Measure:

The GDP deflator is an all-encompassing indicator of inflation, as it captures price changes for all goods and services produced within an economy. This makes it a more extensive measure compared to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which only considers specific categories of goods and services that consumers buy.

2. Relative to a Base Year:

Expressed as a percentage of its value in a selected base year, the GDP deflator facilitates comparisons of inflation over different time periods. This relative measure helps in understanding how the overall price levels have shifted by providing a historical context for inflation rates.

3. Accounts for Quality and Quantity Changes:

A significant strength of the GDP deflator lies in its ability to consider both the quantity of goods and services produced and changes in their quality. This quality adjustment provides a more precise assessment of inflation compared to some other inflation indices, as it acknowledges improvements in products and services over time.

4. Versatile Applications:

The GDP deflator is a valuable tool for diverse purposes:

- For Policymakers: It aids government officials in evaluating the success of economic policies and adjusting monetary and fiscal strategies based on current inflation trends.

- For Businesses: Companies utilize the GDP deflator to inform investment choices, as understanding inflation is critical for anticipating costs, setting prices, and gauging overall economic conditions.

- For Consumers: It helps individuals comprehend how inflation affects their purchasing power, allowing for more informed decisions regarding spending and saving.

What is a Base Year?

In the context of evaluating a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the base year serves as a reference point for comparing economic performance over different time periods. It designates a specific year where the prices of goods and services are considered “normal” or “average.” This allows economists to adjust for inflation, isolating genuine growth in economic output beyond the effects of changing price levels.

For India, the current base year for GDP calculations is 2011-12. This means that all GDP figures are expressed in terms of prices that were prevalent during that fiscal year. Consequently, economists can compare economic growth between various periods—such as from 2015-16 to 2022-23—without the distortion caused by inflation. Regular updates to the base year are essential to maintain the accuracy and relevance of GDP data. Typically, the base year is adjusted every five years to reflect shifts in the economic structure and composition. India last revised its base year in 2015, changing from 2004-05 to 2011-12.

Why India Needed a New Base Year for National Accounts: Understanding the 2017-18 Revision

In the revised series, which aligns with international practices, estimates are provided as Gross Value Added (GVA) at basic prices. The term “GDP at market prices” will now simply be referred to as “GDP.” This allows for a consistent approach to measuring the economic output. The GDP at market prices is calculated by adjusting GVA at basic prices to account for product taxes and subsidies.

- Gross Value Added (GVA) at Basic Prices is calculated using the formula: [ {GVA at Basic Prices} = {Compensation of Employees} + {Operating Surplus} + {Mixed Income} + {Consumption of Fixed Capital (CFC)} + {Production Taxes} – {Production Subsidies}]

- GVA at Factor Cost (previously referred to as GDP at factor cost) is defined as: [ {GVA at Factor Cost} = GVA at Basic Prices} – ({Production Taxes} – {Production Subsidies})]

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is represented as: [{GDP} = {GVA at Basic Prices} + {Product Taxes} – {Product Subsidies}]

The Dynamic Economy and the Need for Rebasing

The economy is constantly evolving due to advancements in production methods, technology, and shifts in consumer demand. These changes necessitate periodic updates to National Accounts Statistics to accurately reflect the real size and structure of the economy.

Rebasing exercises serve several purposes:

1. Update Base Prices: New base prices are established that coincide with current economic conditions.

2. Incorporate New Data Sources: The rebasing process integrates fresh data sources, which provide a more accurate depiction of the evolving economic landscape.

Comprehensive Coverage:

The revised series includes data from various reliable sources, such as the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA 21) database and inputs from local organizations. This leads to a more comprehensive representation of both the corporate and unorganized sectors, which were previously underrepresented, relying mainly on data from the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Industrial Outlook Survey and Annual Survey of Industries (ASI).

Shift to Enterprise Approach:

The new series moves towards an enterprise-level analysis rather than merely establishment-based data, capturing a broader range of activities undertaken by manufacturing entities. This provides a more complete understanding of economic contributions.

Enhanced Unorganized Sector Data:

Recent National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) surveys have improved the accuracy of data regarding the unorganized sector, ensuring that sectors often overlooked in traditional data sources are included.

Focus on GVA:

Industry-specific estimates are now highlighted as Gross Value Added (GVA) at basic prices, offering deeper insights into the economic value generated within each sector.

Differentiation of Production and Product Taxes/Subsidies:

The new series makes a clear distinction between production taxes and product subsidies, providing a better understanding of their individual impacts on different sectors of the economy.

Impact on Data Interpretation

Due to these changes in the base year and methodology, growth rates in various sectors may differ when compared to the old series. For example, sectors like manufacturing might report higher value additions because of the inclusion of associated activities, while others could see a decrease in their GVA figures. As a result, the relative significance of different sectors within the overall economy may also shift, reflecting the improved data coverage and the updated sources used for analysis.

Understanding Potential GDP and Its Importance for India

Potential GDP is defined as the maximum level of economic output that a nation can achieve when it efficiently utilizes all available resources—such as labor, capital, and technology—while operating at full employment. This concept is significant because it represents the sustainable level of economic activity that can be maintained without leading to inflation. Essentially, potential GDP provides a benchmark for assessing the health of the economy and its capacity for growth.

The Importance of Potential GDP in the Indian Context

For India, achieving its full potential GDP is crucial to unlocking the country’s economic capabilities and driving long-term growth. However, a variety of factors contribute to what is known as the GDP Gap—the difference between the economy’s potential output and its actual output. This gap indicates areas where the economy is not performing to its full capacity and highlights the potential for improvement. Several key factors influence this GDP Gap:

1. Gender Inequality:

Research indicates that addressing gender disparities in labor force participation could significantly enhance India’s potential GDP by up to 27%. By promoting equal opportunities for women and empowering them to participate fully in the workforce, India can drastically improve its economic output. This would not only enhance families’ incomes but also contribute to economic growth as a whole.

2. Unemployment and Underemployment:

A vibrant and engaged workforce is a fundamental requirement for economic expansion. High rates of unemployment and underemployment can hinder progress. By implementing effective policies and investing in skill development programs, the government can better utilize its labor resources. This would involve not only creating new jobs but also ensuring that individuals are equipped with the necessary skills to fill available positions, thus improving productivity.

3. Technological Adoption:

Embracing innovative technologies and modern production techniques is essential for boosting efficiency and productivity. For India to enhance its potential GDP, substantial investments in research and development are necessary. Encouraging various sectors to adopt advanced technologies will not only streamline processes but also lead to higher quality outputs and lower costs, contributing to overall economic vitality.

4. Regulatory Framework:

A transparent and efficient regulatory environment plays a critical role in facilitating business operations and attracting both domestic and foreign investments. Simplifying bureaucratic processes and reducing administrative hurdles can promote entrepreneurship and stimulate economic activities. By creating a more user-friendly experience for businesses, India can foster an environment conducive to growth and innovation.

Positive Developments Impacting Potential GDP

Several recent developments indicate progress toward enhancing India’s potential GDP:

- Implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST): The introduction of GST has significantly transformed India’s tax landscape. It is estimated that this reform has boosted India’s potential GDP by approximately 6.7% within five years of its implementation. By simplifying the tax system, GST has improved efficiency and compliance throughout the economy, thereby enhancing economic performance.

- Emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI): The rapid advancement of AI technologies presents enormous opportunities for India’s economic growth. According to NASSCOM, AI is projected to contribute an additional $450 billion to $500 billion to India’s GDP by 2025. By investing in AI research and development, India can unlock substantial economic benefits, driving innovation across various sectors and increasing overall productivity.

Methods of Calculating National Income (or GDP)

Production Approach: Summing up the value added at each stage of production.

Expenditure Approach: Calculating total spending on final goods and services.

Income Approach: Summing up all incomes earned in the production of goods and services.

Production or Value-Added Method

One of the primary approaches for calculating national income is the Production or Value-Added Method. This method is also referred to as the Output Method or Value-Added Method, and it focuses on quantifying the economic contributions of different sectors within the economy.

Key Features of the Production or Value-Added Method:

- Estimation of National Income: The value-added method estimates national income by assessing the incremental value that is added at each stage of production within various economic sectors. This involves analyzing how much value each sector contributes to the overall economy.

- Difference Measurement: This method calculates the difference between the total value of goods and services produced (known as the output) and the value of goods and services utilized in the production process (referred to as intermediate consumption). By doing this, it provides a clearer and more accurate depiction of an economy’s productive capacity.

- Comprehensive Picture: The value-added approach offers a holistic view of economic production, as it accounts for the varying contributions made by different sectors—such as agriculture, manufacturing, and services—at each stage of production.

- Step-by-Step Calculation: The calculation involves subtracting intermediate consumption from the total output value at each stage of production in different sectors. This allows for a granular analysis of how value accumulates in the production chain.

- Application Across Sectors: This method is widely used for estimating GDP, as it effectively highlights the sector-wise contributions to overall economic output. It can clearly illustrate the performance of various industries and their impact on the national economy.

- Understanding Intermediate Consumption: It is essential to note that intermediate consumption refers to the inputs or raw materials used to create final goods. These inputs are subtracted while computing Gross Value Added (GVA) to avoid double-counting the value of a product—once as a finished product and again in the form of raw materials used in production.

Formula Representation

The formula to calculate Gross Value Added (or GDP at Market Prices) can be expressed as: [{(GVA or GDP) MP} = {Value of Output of all Sectors} – {Intermediate Consumption of all Sectors}]

Expenditure Method (Final Expenditure Approach)

One of the key approaches for calculating national income is the Expenditure Method, also known as the Final Expenditure Method. This approach focuses on assessing the total spending on final goods and services within an economy over a specific period. It measures the demand side of economic activity and is commonly used in macroeconomic analysis.

Key Features of the Expenditure Method:

- Estimation of National Income: The Expenditure Method estimates national income by calculating the aggregate expenditure incurred by various sectors—households, businesses, government, and foreign entities—on final goods and services produced within the country.

- Component-Based Calculation: This method relies on the sum of four key components: Consumption (C), Investment (I), Government Expenditure (G), and Net Exports (X – M). Each component reflects a distinct type of economic activity, contributing to a comprehensive estimate of total output.

- Exclusion of Intermediate Goods: To avoid double counting, the method includes only final goods and services in the calculation. Intermediate goods, which are used in the production of other goods, are excluded since their value is already embedded in the price of final goods.

- Sectoral Contributions via Spending: While not directly showing sectoral output like the production method, the expenditure approach implicitly reflects the performance of sectors based on demand patterns—for example, high consumer spending indicates a strong retail/services sector.

- Reflects Aggregate Demand: This method gives insight into the overall aggregate demand in the economy, helping policymakers understand inflationary trends, investment cycles, and consumption behavior.

- Calculation Formula: GDP=C+I+G+(X−M)

Where:

- C = Private Final Consumption Expenditure

- I = Gross Capital Formation (investment)

- G = Government Final Consumption Expenditure

- X = Exports of goods and services

- M = Imports of goods and services

Income Method (Factor Income Approach)

Another essential approach for computing national income is the Income Method, also called the Factor Income Approach. This method emphasizes the earnings of factors of production—land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship—within the domestic economy.

Key Features of the Income Method:

- Estimation of National Income: The Income Method estimates national income by summing up all incomes earned by individuals and institutions involved in the production of goods and services. These include wages, rents, interests, profits, and mixed incomes.

- Focus on Factor Earnings: The approach highlights how income is distributed among the owners of various factors of production:

- Wages and salaries for labor

- Rent for landowners

- Interest for capital providers

- Profits for entrepreneurs

- Mixed Income for self-employed individuals (who supply multiple factors)

- Inclusion of Net Indirect Taxes: To arrive at GDP at market prices, Net Indirect Taxes (Indirect Taxes – Subsidies) are added to factor incomes. This ensures alignment with other GDP approaches.

- Captures Distributional Aspects: This method provides a clearer picture of income distribution in the economy and is especially useful for analyzing wage trends, business earnings, and overall economic welfare.

- Exclusion of Transfer Payments: Transfer payments like pensions, unemployment benefits, and subsidies are excluded, as they do not reflect current production.

- Calculation Formula:

National Income=Compensation of Employees+Rent+Interest+Profits+Mixed Income

National Income} = {Compensation of Employees} + {Rent} + {Interest} + {Profits} + {Mixed Income}

National Income=Compensation of Employees+Rent+Interest+Profits+Mixed Income

To get GDP at market prices:

GDP (mp) =National Income + Net Indirect Taxes + Depreciation

{GDP}{{mp}} = {National Income} + {Net Indirect Taxes} + {Depreciation}

Feature | GVA (Gross Value Added) | GDP (Gross Domestic Product) |

Definition | Measures the value added by each sector (agriculture, industry, services) at each stage of production. | Measures the total market value of all final goods and services produced in a country within a specific period. |

Formula | GVA = GDP – Net Factor Income (Income paid abroad – Income received from abroad) | GDP = GVA + Net Taxes (Taxes earned – Subsidies provided) |

Focus | Provides a granular view of sectoral contributions to the economy. | Provides a broader view of overall economic performance. |

Significance | Helps identify areas for sector-specific growth and assess sectoral performance. | Used for international comparisons and measuring overall economic health. |

Use Cases | Policymakers use GVA to target interventions and track sectoral progress. | Investors and analysts use GDP to assess market potential and compare economies. |

India’s Growth (2024 Q2) | 7.4% growth | 7.6% growth |