Sources of Ancient Indian History

Sources of Ancient Indian History

What is History?

Understanding the Origin of the Word “History”

The term history finds its roots in the ancient Greek word ‘Historia’, which means “inquiry” or “investigation.” At its core, history is the knowledge that emerges from examining and understanding past events. It represents a systematic exploration into the human past — uncovering stories, patterns, and lessons that shape our present and influence our future.

In simple terms, history is not just a record of what happened, but a thoughtful inquiry into why and how those events unfolded. It allows us to connect with the lives, cultures, and experiences of those who came before us, offering insight into the evolution of human society.

Classification of the Timeline in Historical Studies

Historians classify the study of history based on the development of tools, the advent of writing, and modes of communication. Broadly, history is divided into three main phases: Pre-history, Proto-history, and History, each reflecting a different stage in human development.

1. Pre-history

Pre-history refers to the period before the invention of writing. Our understanding of this era comes primarily from archaeological evidence such as tools, cave paintings, and fossils. It is further divided into the following ages:

Palaeolithic Age (Old Stone Age)

Derived from the Greek word lithos meaning stone, the Palaeolithic Age marks the earliest use of stone tools. This period extends from approximately 2.5 million years ago to 11,700 years ago. The tools were typically rough and unpolished, and it was during this era that early humans evolved from their proto-human ancestors.

Mesolithic Age (Middle Stone Age)

Spanning from around 11,700 years ago to 6000 BCE, the Mesolithic Age saw the development of microliths—small, refined stone tools. People began domesticating animals and experimenting with agriculture, marking a significant shift from a purely hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The timeline of this age varies by region.

Neolithic Age (New Stone Age)

Generally ranging from 6000 BCE to 1000 BCE, this period is characterized by the advent of agriculture, the domestication of plants and animals, and settled life. People used polished stone tools, microlithic blades, and bone implements. Housing evolved into structured circular or rectangular dwellings.

Chalcolithic Age (Stone-Copper Age)

Around 3000 BCE, humans began using copper alongside stone tools. The term is derived from the Greek khalkos (copper). This period marked the first use of metal, resulting in improved agricultural practices. People grew cereals, pulses, and cotton, and animal domestication became more widespread.

2. Proto-history

Proto-history refers to the stage where cultures had some form of communication or script but lacked a fully developed writing system. Civilizations in this phase are often mentioned in the texts of other literate societies.

Example: The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), whose script remains undeciphered, is mentioned in the records of the Mesopotamian civilization. Despite the presence of symbols and inscriptions, the lack of a fully understood written language places the IVC in the proto-historic category.

3. History

History begins with the invention of writing, which enables the documentation of events. This era allows historians to reconstruct past societies using written records and archaeological evidence.

Example: The edicts of Emperor Ashoka, inscribed on rocks and pillars, provide invaluable insights into the politics, society, religion, and economy of his time.

Sub-divisions of the Historical Period

Historians further divide recorded history into four broad sub-periods:

Ancient History

This period includes events before the widespread use of paper. Sources from this era include inscriptions on stone, metal plates, and palm leaves, as well as monumental records.

Medieval History

Globally, the medieval period spans from roughly 500 AD to 1500 AD. In the context of Indian history, it extends from the 11th century to around 1750 AD. The adoption of paper during this era led to an explosion of written records, including legal documents, religious texts, tax records, and historical chronicles.

Modern History

In European history, the modern period begins after the end of the Middle Ages, around 1500 AD. In Indian history, it typically refers to the time from the decline of the Mughal Empire to Indian Independence in 1947, encompassing the British colonial period.

Contemporary History

This refers to post-1947 Indian history, following Independence. On a global scale, this period often includes significant 20th-century events such as World War I, World War II, and the Cold War, leading up to the present day.

The classification of historical timelines helps us understand human progress—from early tool use to complex societies with written records. By dividing history into these phases, historians can better analyze and interpret the evolution of civilizations across different regions and time periods.

Sources of Ancient Indian History

All events of history depend on the sources through which a particular narrative is written. There are two types of historical sources for understanding our ancient Indian history, archaeological and literary sources. Further, both sources can be further divided into various categories of sources.

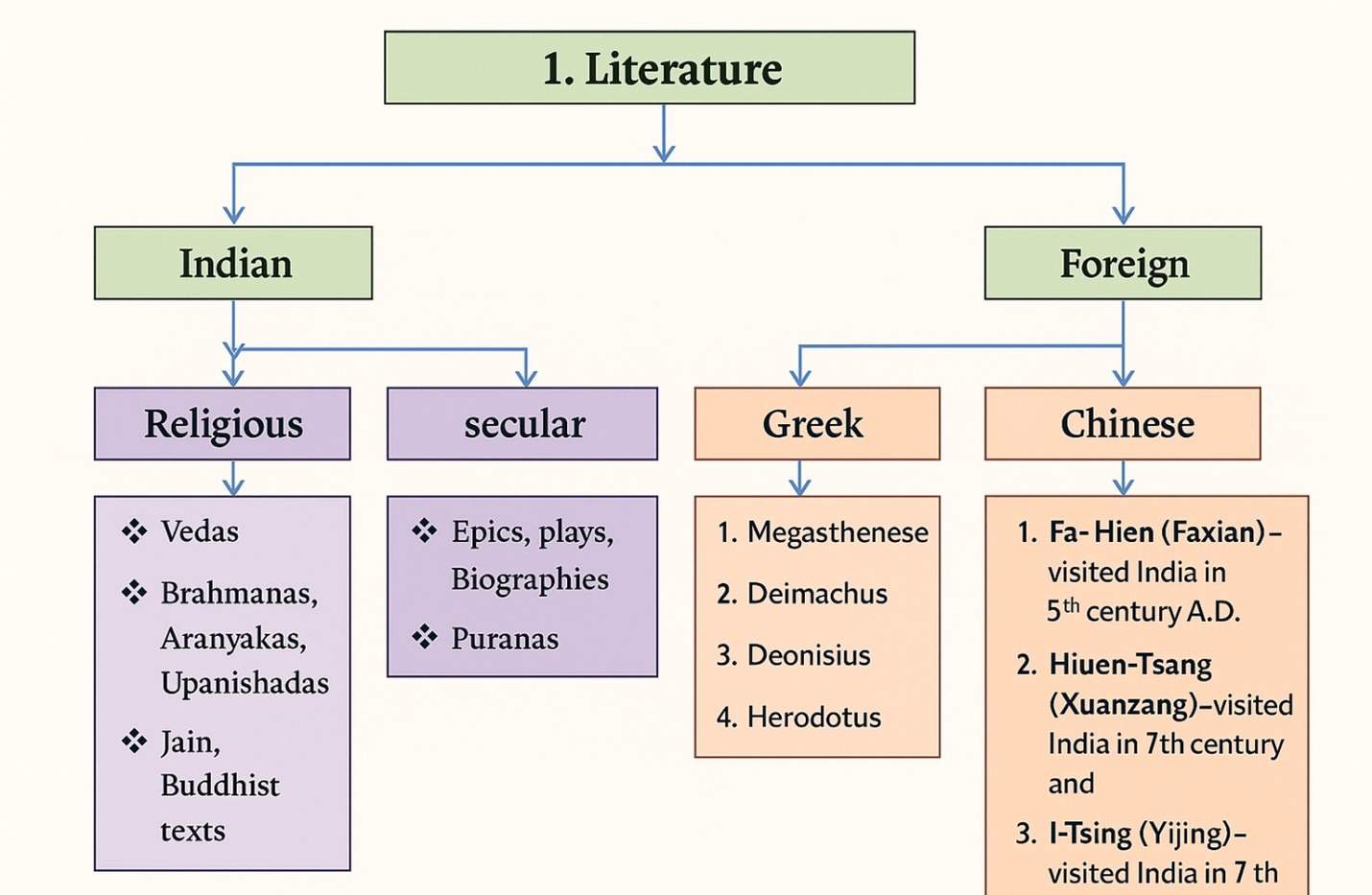

1. Literary Sources

Brahminical Literature

Shruti Texts in the Hindu Tradition

In Hindu philosophy, the Vedas are revered as Shruti, meaning “that which has been heard”. They are believed to be eternal truths, revealed to the rishis (seers) either through deep meditation or divine inspiration. In contrast, the Smriti (literally “that which is remembered”) texts include the Vedangas, Puranas, epics, Dharmashastras, and Nitishastras.

The word Veda is derived from the Sanskrit root vid, meaning “to know”, and translates to “knowledge.” There are four Vedas: Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva. Each Veda is composed of four parts: Samhita, Brahmana, Aranyaka, and Upanishad, though the distinctions among these sections can sometimes blend.

1. Rig Veda

The Rigveda is the oldest of the four Vedas and is often called “the first testament of mankind.” It comprises 1,028 hymns (suktas) divided across 10 mandalas (books). These hymns, known as richas, total 10,580 in number and include some of the world’s oldest surviving poetry, known for its philosophical depth and poetic beauty.

- The 2nd and 7th Mandalas are considered the earliest compositions and are referred to as the ‘Vansha Mandalas.’

- The 8th Mandala, found in handwritten form, is known as ‘Khila’, while the 1st and 10th Mandalas are termed ‘Kshepak.’

- The 10th Mandala, a later addition, contains the famous Purusha Sukta, which symbolically describes the creation of the four varnas (castes) from different parts of the cosmic being.

2. Sama Veda

The Samaveda is essentially a collection of melodies, with most of its 1,810 verses borrowed from the Rigveda. These hymns were meant to be sung during the Soma sacrifices, highlighting the musical and ritualistic aspects of Vedic practices.

The Sama Veda is divided into two parts:

- Purvarchika, comprising six subdivisions known as Apathakas

- Uttararchika, with nine subdivisions called Prapathakas

This Veda laid the foundation for Indian classical music traditions.

3. Yajur Veda

The Yajurveda focuses on the performance of rituals and sacrifices. It includes over 2,000 hymns, spread across 40 chapters, and is often referred to as the “Book of Sacrificial Prayers.” The text is a practical guide for priests conducting Vedic rituals.

It has two major recensions:

- Krishna Yajurveda: A mix of mantras and commentaries

- Shukla Yajurveda: Contains mantras with separate prose explanations

The five known branches are:

- Kasthak, Kapishthal, Maitrayani, and Taittiriya (Krishna Yajurveda)

- Vajasaneyi (Shukla Yajurveda)

The final chapter of the Yajurveda, the Isha Upanishad, is a philosophical text exploring metaphysical ideas, while the other parts mainly deal with laws and procedures of various yajnas (sacrifices).

4. Atharva Veda

The Atharvaveda is the youngest of the four Vedas and significantly different in content and tone. Unlike the other three, which focus on rituals and hymns, the Atharvaveda includes charms, spells, healing practices, and insights into folk beliefs and daily life.

- It contains 731 hymns and 5,987 mantras, with around 1,200 borrowed from the Rigveda.

- Divided into 20 books, it offers guidance on topics ranging from medicine and magic to philosophy and society.

- The two surviving recensions are Shaunaka and Pippalada.

The Atharvaveda is also known as the Brahmaveda or Atharvangirasveda. For centuries, it was excluded from the Vedic canon due to its focus on popular and esoteric traditions. Today, it is recognized for its rich reflection of ancient Indian folk culture and everyday spiritual practices.

The four Vedas—Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva—form the foundation of Vedic literature and encapsulate the spiritual, philosophical, ritualistic, and practical wisdom of ancient India. As Shruti texts, they are considered timeless and universal truths, passed down through generations by oral tradition and later preserved in written form. Understanding these sacred texts offers invaluable insights into the intellectual and cultural fabric of early Indian civilization.

Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads: The Core of Vedic Literature

Brahmanas

The Brahmanas are detailed prose texts that explain the Samhita portions of the Vedas. They elaborate on sacrificial rituals, their procedures, significance, and expected outcomes. Each Veda is associated with one or more Brahmanas:

- Rigveda: Aitareya and Kaushitaki Brahmanas, composed by Hotri priests.

- Yajurveda:

- Taittiriya Brahmana (linked to the Krishna Yajurveda).

- Shatapatha Brahmana (linked to the Shukla Yajurveda), composed by Adhvaryu priest Yajnavalkya. This text traces the cultural development from Kuru-Panchala to Videha.

- Samaveda: Three Brahmanas—Tandya Mahabrahmana, Khila Brahmana, and Jaiminiya Brahmana, composed by Udgatri priests.

- Atharvaveda: Gopatha Brahmana.

Aranyakas

The Aranyakas, or “forest books,” provide a symbolic and philosophical interpretation of Vedic rituals. They were intended for forest-dwelling hermits and ascetics, serving as a bridge between ritualism (Karma Marga) and spiritual knowledge (Gyana Marga).

There are seven Aranyakas:

- Aitareya, Sankhyayana, Taittiriya, Maitrayani, Madhyandina, Talavakara, and Jaiminiya.

Unlike the Brahmanas, the Aranyakas move away from external rituals and emphasize meditation, moral virtues, and inner realization.

Upanishads

The Upanishads mark the philosophical culmination of the Vedic texts. The word Upanishad combines upa (near) and nishad (to sit), implying sitting near a teacher to receive esoteric knowledge.

There are 108 Upanishads, of which 13 are considered principal. These texts explore profound ideas related to Atman (self) and Brahman (universal spirit), the nature of reality, creation, and liberation.

Some of the important Upanishads include:

- Isha, Kena, Katha, Prashna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, Brihadaranyaka, Kaushitaki, Shvetashvatara, and Jabala.

The Mundaka Upanishad gave rise to India’s national motto: “Satyameva Jayate” (Truth alone triumphs).

Most Upanishads were composed between 800 BCE and 500 BCE. They are anti-ritualistic, advocating self-realization, meditation, and detachment as paths to salvation. Many of them use narrative and dialogue to impart deep spiritual teachings.

Smriti Texts: The Recollection of Sacred Knowledge

Vedangas

The Vedangas are six auxiliary disciplines developed to support the correct understanding and performance of Vedic rituals. Composed during the later Vedic period, they include:

- Shiksha – Phonetics and pronunciation of Vedic mantras.

- Kalpa – Ritual instructions, duties, and sacraments.

- Vyakarana – Grammar and linguistic analysis.

- Nirukta – Etymology and interpretation of difficult Vedic terms. Nirukta by Yaskacharya is a seminal work.

- Chhanda – Study of Vedic meters. Chhandasutra was composed by Acharya Pingala.

- Jyotisha – Vedic astronomy and astrology, crucial for determining auspicious times for rituals. The Jyotisha Vedanga contains approximately 400 verses.

Epics: Ramayana and Mahabharata

Ramayana

The Ramayana, composed by Valmiki, is considered the oldest epic in the world and is known as Adi Kavya (the first poem). It contains 24,000 shlokas across seven Kandas (books):

- Bal Kand, Ayodhya Kand, Aranya Kand, Kishkindha Kand, Sundar Kand, Lanka Kand, and Uttar Kand (the first and last being later additions).

Originally composed around the 5th century BCE, the Ramayana evolved from 6,000 verses to 12,000 and finally to its present form of 24,000.

Mahabharata

The Mahabharata, attributed to Ved Vyasa, is the longest epic in the world, comprising 100,000 shlokas in 18 Parvas (books). Among them, Shanti Parva is the largest.

- Initially known as Jaya Samhita with 8,800 verses.

- Later expanded to 24,000 verses as the Bharata.

- Eventually grew into the Mahabharata or Shatasahastri Samhita.

It includes the Bhagavad Gita, found in the Bhishma Parva, and is also referred to as the “Panchama Veda” or the Fifth Veda due to its spiritual and philosophical depth.

Puranas

The word Purana means “ancient.” There are 18 major Puranas and 19 Upapuranas. These texts narrate cosmology, genealogies of gods and sages, moral teachings, and the histories of dynasties like the Mauryas, Andhras, Shishunagas, and Guptas.

The 18 Mahapuranas are:

- Brahma, Padma, Vishnu, Shiva, Bhagavata, Narada, Markandeya, Agni, Bhavishya, Brahma Vaivarta, Linga, Varaha, Skanda, Vamana, Kurma, Matsya, Garuda, and Brahmanda.

The Matsya Purana is considered the oldest among them. These were compiled by Lomaharshana or his son Ugrashrava.

Smritis

The Smritis, meaning “that which is remembered,” are texts that complement the Vedas and help regulate personal, social, and legal life. They are also considered part of divine revelation but are secondary to the Shruti texts.

Six prominent Smritis include:

- Manu Smriti

- Yajnavalkya Smriti

- Narada Smriti

- Parashara Smriti

- Brihaspati Smriti

- Katyayana Smriti

These works offer guidance on law, ethics, duties, and customs, playing a critical role in the development of ancient Indian jurisprudence and social order.

From the ritualistic Brahmanas to the philosophical Upanishads, and from the moral epics to the regulatory Smritis, Hindu scripture forms a vast and intricate body of sacred knowledge. The Shruti and Smriti texts together illuminate every dimension of life—ritual, moral, philosophical, and cosmic—guiding humanity toward knowledge, virtue, and liberation.

Buddhist Literature

Buddhist literature is broadly categorized into canonical and non-canonical texts. Canonical texts form the foundational scriptures that define the core doctrines and principles of Buddhism. These were developed and preserved differently across various Buddhist traditions such as Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana, resulting in versions in Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan.

The Tripitaka (Three Baskets)

The canonical literature of Buddhism is most famously compiled as the Tripitaka or Tipitaka, meaning “Three Baskets.” The oldest and most complete version is the Pali Tipitaka, preserved by the Theravada school. Composed in Pali, a literary language derived from dialects of the Magadha region, it comprises:

1. Sutta Pitaka: A collection of the Buddha’s discourses, primarily in dialogue form. These teachings address a range of doctrinal and ethical subjects. This Pitaka includes five major Nikayas:

- Digha Nikaya (Long Discourses)

- Majjhima Nikaya (Middle-Length Discourses)

- Samyutta Nikaya (Connected Discourses)

- Anguttara Nikaya (Numerical Discourses)

- Khuddaka Nikaya (Minor Collection), which includes well-known texts such as:

- Jataka Tales – narratives of the Buddha’s previous births

- Dhammapada – a collection of moral and ethical verses

- Theragatha and Therigatha – verses by early monks and nuns, offering a unique perspective on renunciation, especially from women.

2. Vinaya Pitaka: This contains rules and regulations for monks and nuns of the Sangha (monastic community), including the Patimokkha, which lists offenses and corresponding atonements.

- Abhidhamma Pitaka: A more analytical and systematic presentation of Buddhist teachings found in the Sutta Pitaka, employing classification, logic, and philosophical analysis.

Buddhist Councils and Preservation

According to tradition:

- The First Buddhist Council at Rajagriha, immediately after the Buddha’s death, recited and preserved the Sutta and Vinaya Pitakas.

- The Second Council at Vaishali, held a century later, reaffirmed these teachings.

- The Third Council, convened during Emperor Ashoka’s reign in the 3rd century BCE, contributed significantly to the standardization and propagation of these texts.

Non-Canonical Pali Literature

Non-canonical texts also played a crucial role in shaping Buddhist thought:

- Milindapanha: A philosophical dialogue between Indo-Greek King Menander (Milinda) and the monk Nagasena.

- Nettipakarana (Nettigandha): A guidebook summarizing Buddhist doctrine, attributed to the disciple Kaccana.

- Buddhaghosha’s Commentaries: Especially the Visuddhimagga (Path of Purification), written in the 5th century CE, which became a cornerstone of Theravada scholasticism.

- Chronicles like Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa: Historical-cum-mythological narratives that document the life of the Buddha, the Buddhist councils, the Mauryan dynasty, and the arrival of Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Sanskrit and Hybrid Buddhist Literature

While the Theravada tradition primarily used Pali, many Mahayana and other schools composed their texts in Sanskrit or Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit (a mix of Sanskrit and Prakrit). Notable examples include:

- Sarvastivada Vinaya: The monastic code of the Sarvastivada school, a prominent early Buddhist sect.

- Lalitavistara Sutra: A hagiographic account of the Buddha’s life, showing early Mahayana influence.

- Mahavastu: A sacred biography detailing the evolution of the monastic order, written in hybrid Sanskrit.

- Buddhacharita by Ashvaghosha: A poetic biography of the Buddha.

- Avadana Literature: Collection of moral tales that often illustrate the workings of karma.

Mahayana Buddhist Texts and Thinkers

The Mahayana tradition produced a vast and complex body of literature. Key texts include:

- Prajnaparamita Sutras: A central collection dealing with the “Perfection of Wisdom,” foundational to Mahayana philosophy.

- Commentaries by Sanghabhuti (4th century CE): He helped interpret and spread Mahayana doctrines in China, especially the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras.

- Works by leading Mahayana philosophers:

- Nagarjuna – founder of the Madhyamaka school

- Asanga and Vasubandhu – key figures of the Yogachara tradition

- Aryadeva, Buddhapalita, Dignaga – influential thinkers in Buddhist logic and epistemology

Buddhist literature—both canonical and non-canonical—offers a rich tapestry of philosophical insights, ethical teachings, historical chronicles, and spiritual guidance. From the foundational Pali Tipitaka to the sophisticated works of Mahayana masters, this vast body of work continues to inspire, guide, and shape Buddhist thought and practice across the world.

Jain Literature

Jain literature, deeply rooted in the spiritual and philosophical traditions of Jainism, is broadly classified into canonical (Agama/Siddhanta) and non-canonical texts. These texts, composed in various Prakrit dialects and later in Sanskrit, reflect the core tenets, ethical values, cosmology, and monastic codes of the Jain community.

Canonical Literature (Agamas/Siddhanta)

The sacred texts of Jainism are collectively known as the Agamas or Siddhanta. The earliest of these were written in Ardha-Magadhi, an eastern dialect of Prakrit, closely associated with the region of ancient Magadha.

Jainism eventually branched into two major sects—Shvetambara (white-clad) and Digambara (sky-clad)—each preserving and interpreting the canon in its own way.

Shvetambara Canon

The Shvetambara Jain canon consists of a comprehensive body of literature:

- 12 Angas (fundamental texts)

- 12 Upangas (subsidiary texts)

- 10 Prakirnas (Painnas) (miscellaneous texts)

- 6 Cheda Sutras (Cheya Suttas) (disciplinary texts)

- 4 Mula Sutras (basic texts)

- Additional individual works such as the Nandi Sutra and Anuyogadvara Sutra

These texts cover a wide range of topics—from monastic discipline and ethical conduct to metaphysics, cosmology, and logic.

According to Shvetambara tradition, the Angas were compiled during a council held at Pataliputra. The complete canon was finalized at a significant council convened in the 5th or 6th century CE in Valabhi, Gujarat, under the leadership of Devarddhi Kshamashramana. While some portions of the canon may date as far back as the 5th or 4th century BCE, revisions and additions continued until the 6th century CE.

Digambara Perspective

The Digambara sect does not accept the current Shvetambara canon as authentic, believing that the original teachings were lost over time. Instead, they rely on other texts, many of which are considered non-canonical but highly authoritative within the tradition.

Prominent Jain Texts and Authors

Trishashtishalaka Purusha Charita

Authored by Acharya Jinasena and later completed by his disciple Gunabhadra in the 9th century, this monumental work—also known as the Trishashtilakshana Mahapurana—details the lives of 63 illustrious Jain figures:

- 24 Tirthankaras

- 12 Chakravartins

- 9 Vasudevas

- 9 Baladevas

- 9 Prativasudevas

It combines cosmology, mythology, and Jain moral philosophy, and is a central text in the Digambara tradition.

Adi Purana

Also written by Jinasena, this 9th-century text narrates the life of Rishabhanatha (Adinatha), the first Tirthankara. It reflects the spiritual ideals of Jainism and serves as a model of devotion, asceticism, and righteousness.

Harivamsha Purana

Composed in the 8th century, this Jain retelling of the Mahabharata includes stories of the Kauravas, Pandavas, Krishna, Balarama, and other legendary figures, reinterpreted through a Jain lens. It highlights Jain values like non-violence, detachment, and moral conduct.

Parishishtaparvan (Sthaviravali)

Written by Hemachandra in the 12th century, this historical text traces the lineage of early Jain teachers and provides insights into the political and religious history of ancient India. It is often considered a supplement to the Mahabharata, offering alternative Jain narratives of well-known epics.

Non-Canonical Jain Literature

Non-canonical Jain works, though not part of the official canon, are equally important for understanding the development of Jain thought. These were written in Maharashtri Prakrit, Sanskrit, and sometimes in Apabhramsha.

Key Components:

- Niryuktis (Nijjuttis) – concise explanatory verses

- Bhashyas – detailed commentaries

- Churnis – prose explanations

- Tikas, Vrittis, Avachurnis – medieval Sanskrit commentaries

These commentarial traditions elaborated on canonical texts, often introducing philosophical interpretations, logical analysis, and ethical discourse.

Jain Puranas and Charitas

The Jain Puranas, also known as Charitas (especially in the Shvetambara tradition), serve as hagiographies of Tirthankaras and other Jain saints. Though devotional in tone, these texts also explore themes such as:

- Town planning

- Life-cycle rituals

- Dream interpretation

- Warrior duties

- Ethical kingship

They offer a rich cultural and moral framework that reflects Jain values and practices across centuries. Jain literature, spanning more than two millennia, is a testament to the community’s dedication to spiritual discipline, non-violence, and ethical living. Whether in the form of canonical Agamas or richly layered Puranas and commentaries, these texts continue to illuminate Jain philosophy and inspire scholars, devotees, and seekers across the world.

Secular Literature (Non-Historical & Historical)

S.No. | Work | Author | Period | Description |

1 | Arthashastra | Kautilya (Chanakya) | Mauryan Period | A detailed treatise on politics, economics, and administration. |

2 | Mudrarakshasa | Vishakhadatta | Gupta Period | Describes the overthrow of the Nandas by Chandragupta Maurya with Chanakya’s help. |

3 | Ashtadhyayi | Panini | Pre-Mauryan | A foundational work on Sanskrit grammar; later annotated by Patanjali. |

4 | Gargi Samhita | — | Ancient Period | Mentions the entry of the Yavanas (Greeks) into India. |

5 | Abhijnanasakuntalam, Malvikagnimitram | Kalidasa | Gupta Period | Reflect societal and cultural conditions; Malvikagnimitram also mentions the conflict between Yavanas and Pushyamitra Sunga. |

6 | Swapnavasavadatta, Madhyama-vyayoga | Bhasa | Early Classical Period | Depicts socio-political aspects; Madhyama-vyayoga draws from Mahabharata themes. |

7 | Kavyalankara | Bhamaha | Early Medieval Period | A seminal work on poetics and literary theory. |

8 | Natyashastra | Bharata Muni | Ancient Period | Treatise on performing arts: theatre, dance, and music. |

9 | Mahabhashya | Patanjali | 2nd Century BCE | Commentary on Panini’s grammar. |

10 | Devichandraguptam | Vishakhadatta | Gupta Period | Another political drama from the Gupta era. |

11 | Nagananda, Priyadarshika, Ratnavali | King Harshavardhana | 7th Century CE | Dramas highlighting Harsha’s rule and cultural life. |

12 | Harshacharita | Banabhatta | 7th Century CE | Biographical account of Harshavardhana’s life and administration. |

13 | Gaudavaho | Vakpati Raj | 8th Century CE | Narrates King Yashovarman’s victory over Gauda. |

14 | Navsahsanka Charit | Padmagupta Parimal | 10th Century CE | Chronicles the Parmaras of Malwa. |

15 | Vikramankadevacharita | Bilhana | 11th Century CE | Eulogizes the Chalukya King Vikramaditya VI. |

16 | Hammira Mahakavya | Nayachandra Suri | 15th Century CE | Life story of Hammira of Ranthambore. |

17 | Nitivakyamrita | Somadeva Suri | 10th Century CE | Jain text on polity and ethics. |

18 | Avadanashataka | Hāla | Satavahana Period | Anthology of a hundred Sanskrit verses. |

19 | Prithviraj Raso | Chand Bardai | 12th Century CE | Chronicles the life of Prithviraj Chauhan. |

20 | Prithviraj Vijay | Jayanaka | 12th Century CE | Another account of Prithviraj Chauhan’s reign. |

21 | Parmal Raso | Jaganaka | Medieval Period | Describes events from the Rajputana period. |

22 | Rajatarangini | Kalhana | 1148–49 CE | Historical chronicle of Kashmir; considered the first historical text of India. |

23 | Ramacharita | Sandhyakar Nandi | 11th–12th Century CE | Details the reign and achievements of Rampala, the Pala ruler of Bengal. |

Sangam Literature: The Golden Age of Tamil Poetry

Sangam literature represents the earliest known body of Tamil literature, flourishing under the royal patronage of the Pandya kings in ancient Madurai. The term “Sangam” refers to an assembly or academy of Tamil poets and scholars, who are believed to have convened over several centuries to compose and critique poetry, shaping the literary heritage of South India.

The Three Sangams:

According to legend, there were three Sangams, collectively known as Muchchangam.

- The First Sangam is said to have been held in Madurai and attended by gods and legendary sages. Unfortunately, no works from this period have survived.

- The Second Sangam took place at Kapadapuram, with the Tolkappiyam—the earliest extant Tamil grammar and poetics text—being the only surviving work.

- The Third Sangam was again held in Madurai, and some of its literary creations have endured, providing invaluable insight into the history and culture of the Sangam period.

The Sangam Corpus

The Sangam corpus primarily consists of:

- Six of the eight anthologies (Ettutokai or “The Eight Collections”)

- Nine of the ten idylls (Pattuppattu or “The Ten Songs”)

These works were likely composed between the 3rd century BCE and the 3rd century CE. By the mid-8th century, these poems were compiled into anthologies, and later, into super-anthologies such as the Ettutokai and Pattuppattu. The anthologies encompass 2,381 poems attributed to 473 poets, including 30 women poets—a remarkable testament to the inclusivity of Sangam literary culture.

Notable Works and Themes

- Tolkappiyam: Authored by Tolkappiyar, a disciple of the sage Agathiyar, this foundational work covers Tamil grammar and poetics. The lost Agattiyam, attributed to Agathiyar, is believed to have been the first book on Tamil grammar and is considered irretrievably lost.

- Themes: Sangam poetry is broadly categorized into akam (love and personal life) and puram (war, public life, and ethics). This duality reflects the depth and diversity of Tamil society during the Sangam era.

Classification of Sangam Literature

Sangam literature is divided into two main groups:

- Narrative (Melkannakku): Comprising 18 major works, including the eight anthologies and ten idylls, these texts celebrate heroic deeds, wars, and cattle raids.

- Didactic (Kilkanakku): Encompassing 18 minor works, these texts provide moral and philosophical guidance.

Legacy and Later Works

The influence of Sangam literature extended well beyond its era. Notable later works include:

- Tirukkural by Tiruvalluvar: A renowned treatise on ethics, philosophy, polity, and love, often hailed as the “fifth Veda” of Tamil Nadu.

- Silappadikaram by Ilango Adigal: Considered the brightest gem of early Tamil literature, this epic narrates the tragic love story of Kovalan and Kannagi.

- Manimekalai: A sequel to Silappadikaram, this epic follows the adventures and spiritual journey of Kovalan and Madhavi’s daughter, highlighting her conversion to Buddhism.

- Bharatam by Perudevanar: Another significant Tamil epic, further enriching the literary tradition.

Sangam literature stands as a monumental achievement in world literature, offering a vivid window into the ancient Tamil world—its society, values, and artistic expression. Its enduring legacy continues to inspire and inform scholars, poets, and readers alike.

Foreign Travellers’ Writings: Windows into Ancient and Medieval India

Foreign travellers have played a pivotal role in shaping our understanding of India’s rich and diverse past. Their accounts, spanning from ancient Greek historians to medieval Arab scholars and Chinese pilgrims, offer invaluable insights into the subcontinent’s society, culture, economy, and religion.

Greek and Roman Accounts

The earliest references to India in Greek literature appear as early as the 5th century BCE, growing in frequency and detail over the centuries. Among the most renowned works is the Indica by Megasthenes, the ambassador of Seleucus Nikator to the court of Chandragupta Maurya. Although the original text is lost, later Greek writers preserved paraphrases and summaries of its contents, providing glimpses into the Mauryan administration and society.

From the 2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE, numerous Greek and Roman texts referenced India, including the works of Arrian, Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and the anonymous author of the Periplus Maris Erythraei (Periplus of the Erythraean Sea). These sources are particularly significant for understanding the history of Indian Ocean trade, highlighting India’s role as a vibrant hub of commerce and cultural exchange.

Chinese Pilgrims and Buddhist Heritage

Driven by a quest for authentic Buddhist scriptures and spiritual enlightenment, several Chinese monks undertook arduous journeys to India. Their detailed travelogues shed light on religious practices, educational institutions, and daily life in ancient India.

- Faxian (Fa Hien) traveled from 399 to 414 CE, focusing his explorations in northern India. His writings provide valuable information on Buddhist monastic life and pilgrimage sites.

- Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) embarked on his journey in 629 CE, spending over a decade traversing the length and breadth of India. His comprehensive accounts remain critical sources for understanding Indian society, religion, and education during the 7th century.

- Yijing, another eminent Chinese traveller of the 7th century, resided for ten years at the renowned Nalanda monastery, documenting the scholastic and spiritual pursuits of the era.

These pilgrims’ narratives are indispensable for reconstructing the history of Buddhism and the broader cultural landscape of their time.

Arab and Persian Scholars

The rapid expansion of the Arab world, coupled with the rise of Islam and the patronage of the Caliphs, spurred a new wave of intellectual curiosity about India. While early Arab scholars often relied on Greek sources, figures such as Jaihani, Gardizi, and Al-Biruni developed independent and critical perspectives.

- Al-Biruni (Abu Rihan), one of the greatest intellectuals of the early medieval period, journeyed to India to deepen his understanding of its people, languages, and traditions. His magnum opus, Tahqiq-i-Hind, covers a vast array of topics, including Indian scripts, sciences, geography, astronomy, philosophy, literature, beliefs, customs, religions, festivals, rituals, social organization, and laws.

- Al-Biruni’s meticulous observations not only provide a detailed snapshot of 11th-century India but also assist modern historians in dating key historical events, such as the beginning of the Gupta era in 319–320 CE.

Other notable Arab and Persian travellers who chronicled their impressions of India include Suleiman, Al-Masudi, and Ibn Battuta. Literary works such as Firdausi’s Shahnama and Saadi’s Gulistan also contain incidental references to Indian trade and society.

The writings of these foreign travellers remain invaluable historical sources, offering unique, first-hand perspectives on India’s evolving civilization. Their observations continue to enrich our understanding of the country’s ancient and medieval heritage, bridging cultures and centuries through the power of the written word.

Author/Traveller | Book/Work | Subject/Description |

Megasthenes (Greek) | Indica | Valuable information on administration and socio-economic conditions of the Mauryan Empire |

Ptolemy (Greek) | Geography of India | Geographical treatise on India in the 2nd Century AD |

Pliny (Greek) | Naturalis Historia | Accounts of trade relations between Rome and India in the 1st Century AD |

Anonymous (Greek) | Periplus of the Erythraean Sea | Records personal voyage along the Indian coasts in 80 AD |

Fa-Hien (Chinese) | Record of the Buddhist Countries | Records the Gupta Empire in the 5th Century AD |

Hiuen Tsang (Chinese) | Buddhist Records of the Western World | Describes the social, economic, and religious conditions of India in the 5th and 7th centuries AD |

I-tsing (Chinese) | A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago | Studies the Gupta period under Sri Gupta in the 7th Century AD |

Hwuili (Chinese) | Life of Hiuen Tsang | Accounts Hiuen Tsang’s travels in India |

Archaeological Sources

Archaeology—the study of the human past through material remains—is closely connected with history. Material remains range from vestiges of grand palaces and temples to the small, discarded products of everyday human activity such as pieces of broken pottery. They include different things such as structures, artefacts, bones, seeds, pollen, seals, coins, sculptures, and inscriptions. Archaeologists increasingly rely on various scientific techniques in order to obtain precise information about the lives of past communities. These are especially useful in dating archaeological material. Many dating methods are based directly or indirectly on the principle of radioactive decay. Carbon-14 or radiocarbon dating is the best-known of these, but others include thermo luminescence, potassium-argon, electron spin resonance, uranium series, and fission-track dating.

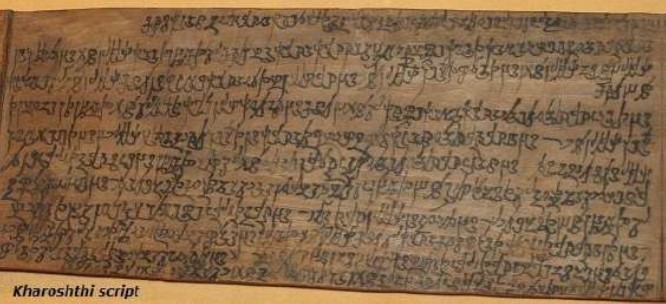

The credit for excavating the Pre-Aryan past goes to Sir William Jones of the Asiatic Bengal Society. James Prinsep, the Secretary of ABS succeeded for the first time in deciphering the Brahmi script. Sir Alexander Cunningham, the father of Indian archaeology, arrived in India in 1831. He judged the ruins of ancient sites of pre-Aryan civilization. He also identified the ruins of the ancient side of pre- Aryan culture. Later on, in 1901, Lord Curzon revived this work and John Marshall was appointed as its director general and he discovered the cities Harappa and Mohenjodara. Rakhal Das Banerji, in 1922, found seals at Mohenjodaro. It was the remains of pre-Aryan civilization. Later, the sites were excavated under the direction of Marshall from 1924 to 1931. Sir R.E. Mortimer Wheeler made important discoveries at Harappa after the Second World War. Indian epigraphists such as Bhanu Daji, Bhagavanlal Indraji, Rajendralal Mitra and R.G. Bahndarkar contributed to the excavations of new sites.

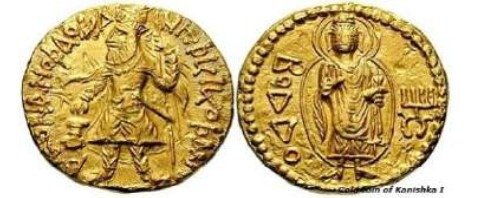

The study of coins is called numismatics. Important historical facts are obtained through it. Samudragupta’s Aswameda coins and lion slayer coins reflect his ambitions and love of hunting. He has been seen playing on a lyre in a coin which gives an idea of his love of music. The Punch Mark Coins (of silver and copper) are the earliest coins of India.

The Kushanas issued gold coins depicting many deities on their coins. The coins of Vima Kadphises bear the figure of Lord Shiva. Thus, coins help discover ideas about the complementary economic condition and provide facts with date that help us in fixing chronology. In Panini’s Astadhyayee, Brahmin literature and Upanishads we find the descriptions of Vedic coins or currency named Nishka, Shatman, Suvarna, and Panishka. The Gold coins of Gupta’s period are quite important in this context. Inscriptions are the words cut on stone or metals. The study of inscriptions is called epigraphy.

Inscriptions are the most reliable evidence and are free from interpolations. Ashokas’s rock-cut edicts, pillar edicts, inscriptions of Kharvela and Allahabad Prasasti by Harisena and the inscriptions found at Khalimpur and Bhagalpur of the Gupta Age are important evidence.

Monuments and buildings reflect the growth of material prosperity and the development of culture. The ancient monuments of Taxshila provide information about the Kushanas and its sculpture imparts the knowledge of Gandhar Kala. The Mauryan history is known by the Stupas, Chaityas and Vihars.

Ancient history forms a vital foundation for understanding our land and its evolution over thousands of years. Exploring ancient details allows us to visualize how regions once were, offering a window into the distant past. The most reliable and valuable means of uncovering this knowledge is through the study of traditional literature written during those times. These literary sources vividly portray the economic structures, religious beliefs, systems of governance, cultural practices, and social norms of early and ancient India, helping us reconstruct and appreciate the richness of our heritage