Wildlife Conservation:

Conservation typically refers to the careful management of both biotic and abiotic resources. It encompasses efforts to avoid the wasteful or detrimental use of these resources. Wildlife conservation specifically focuses on safeguarding wild species and their habitats to maintain the health of natural ecosystems.

Regulating Trade in Wildlife:

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES):

CITES, commonly referred to as the Washington Convention, is a multilateral treaty established among governments to safeguard against the potential threats posed to the survival of wild animal and plant species by international trade in their specimens. The agreement was formulated following a resolution passed by IUCN members in 1963 and officially came into effect in 1975.

CITES is a legally binding agreement for its Parties, which number 184, including the European Union. Nevertheless, it does not replace national legislation. Instead, it establishes a framework that each Party must adhere to. Consequently, the Parties are required to develop their own domestic laws to guarantee the effective implementation of CITES at the national level.

Conference of Parties (CoP):

The CITES Conference of the Parties (CoP) is held every two to three years, bringing together member nations to assess and make decisions regarding the regulation of trade in endangered species. During the CoP, participants will evaluate proposals concerning the addition, removal, or modification of species listings within the CITES appendices.

Functioning of CITES:

CITES regulates international trade in certain species through a licensing framework. Each member country of CITES appoints:

1. Management Authorities: These entities oversee the licensing process. In India, this includes:

The Director of Wildlife Preservation (operating under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change).

2. The Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB), which is responsible for issuing permits.

3. Scientific Authorities: These bodies offer specialized knowledge regarding the impact of trade. In India, the relevant organizations are:

- The Zoological Survey of India.

- The Botanical Survey of India.

- The Wildlife Institute of India.

4. This organizational structure facilitates controlled trade while protecting at-risk species.

5. All activities related to the import and export of species listed under CITES must be conducted with the appropriate authorization from this system.

Types of Protection from over exploitation:

CITES classifies species into three distinct Appendices to manage international trade and safeguard their conservation:

Appendix I:

- This category encompasses species that are critically endangered and face a high risk of extinction, such as gorillas, sea turtles, lady slipper orchids, and giant pandas.

- Currently, it includes 1,082 species.

- Trade regulations: International trade is entirely prohibited, except for non-commercial activities such as scientific research, and necessitates both import and export permits (or re-export certificates).

Appendix II:

- This section comprises species that are not currently endangered but could become so if trade is not regulated, including American ginseng, paddlefish, lions, American alligators, mahogany, and corals.

- The majority of species listed under CITES fall within this category, totaling 37,420 species.

- It also includes “look-alike species,” which are specimens that closely resemble those of species requiring conservation.

- Trade regulations: An export permit or re-export certificate is required; however, no import permit is necessary unless stricter national regulations are in place. These permits ensure that trade does not adversely affect the species’ survival.

Appendix III:

- This Appendix features species that are regulated by individual nations aiming for international collaboration to prevent illegal or unsustainable exploitation, such as map turtles, walruses, and Cape stag beetles.

- Currently, it lists 211 species.

- Trade regulations: Permits or certificates are required for international trade. Unlike Appendices I and II, which necessitate approval at the Conference of the Parties, species can be added or removed from this Appendix by any Party independently.

18th Conference of the Parties to CITES (CoP18), 2019 (Geneva, Switzerland):

Proposals from India:

- Species proposed for upgrade from Appendix II to Appendix I include the Smooth-Coated Otter (VU), Small-Clawed Otter (VU), Indian Star Tortoise (VU), Tokay Gecko (LC), and Wedgefish (CR).

- India also requested the delisting of Indian Rosewood (VU) from Appendix II.

Outcomes:

The Indian Star Tortoise (VU), Small-Clawed Otter (VU), and Smooth-Coated Otter (VU) were successfully reclassified to Appendix I, resulting in a total prohibition on their trade.

19th Conference of the Parties to CITES (CoP19), 2022 (Panama):

Key Highlights:

- A total of 52 proposals were discussed, affecting trade regulations for various species, including sharks, reptiles, elephants, and turtles.

- India’s Operation Turtshield, which targets wildlife crime related to turtles, was acknowledged.

The inaugural World Wildlife Trade Report was published, indicating that:

- The predominant portion of CITES-regulated trade consists of artificially propagated plants or captive-bred animals.

- Only 18% of the trade pertains to species sourced from the wild, primarily plants.

India’s Proposals at CoP19:

- Revisions to Appendix I: India suggested elevating the status of the Red-Crowned Roofed Turtle (CR) and Leith’s Softshell Turtle (CR) from Appendix II to Appendix I.

- New Addition to Appendix II: India successfully advocated for the inclusion of the Jeypore Ground Gecko (EN) in Appendix II.

- Jeypore Ground Gecko: This species is located in the Eastern Ghats, specifically in southern Odisha and northern Andhra Pradesh, at altitudes ranging from 1,100 to 1,400 meters. It faces threats from the pet trade, habitat destruction, environmental degradation, forest fires, tourism, quarrying, and mining activities.

- IUCN Status: Endangered (EN).

- CITES & WPA Status: Not listed.

- North Indian Rosewood/Shisham (Dalbergia sissoo): The Shisham, classified as Least Concern (LC) and widely available in India, is listed in Appendix II due to difficulties in species identification within the Dalbergia genus.

- Export restrictions, such as the requirement for CITES permits for consignments exceeding 10 kg, have limited the export of Shisham furniture and handicrafts.

India’s initiative at CoP19:

- Consignments weighing less than 10 kg can now be exported without the need for CITES permits.

- Only the net weight of Shisham timber is taken into account for these calculations.

Additional Proposals:

- Sea Cucumbers (Thelenota): The European Union proposed the listing of three species under Appendix II due to the high incidence of trafficking from coastal India, a proposal that was accepted at CoP19.

Ivory Trade:

- A global ban on ivory trade has been in effect since 1989, with African elephant populations listed in Appendix I. Subsequently, certain populations from South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe were moved to Appendix II to allow for one-time ivory sales.

- Asian elephants have been listed in Appendix I since 1975, prohibiting the export of ivory.

- At CoP18, Zambia’s proposal to downgrade elephants from Appendix I to II was rejected, and India chose to abstain from voting on a similar proposal at CoP19.

CITES Tiger Enforcement Task Force

- The 19th Conference of the Parties (CoP19) has suggested a provisional budget of $150,000 for the Big Cat Task Force. This task force aims to combat the illicit trade of large felines, including lions, tigers, leopards, and cheetahs, within their natural habitats.

Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE):

Established in 1997 through a CITES Resolution, this initiative aims to track trends and identify the causes of elephant mortality while enhancing the capabilities of elephant range states.

Functionality: The program provides essential data to inform global conservation strategies for both African and Asian elephants and disseminates analyses during annual CITES meetings.

MIKE Sites in Asia (28 Sites Across 13 Countries):

India: Hosts the largest number of sites in Asia, totalling 10.

Other Countries:

- Each of the following countries has 2 sites: Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand.

- Additionally, there is 1 site in each of the following countries: Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

Implementation in Asia:

Since 2017, the IUCN has been executing the MIKE Asia program across two sub-regions:

- South Asia: Includes Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

- Southeast Asia: Comprises Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Funding:

- Donor Dependency: The program is entirely dependent on donor contributions.

- Key Contributor: The European Union has been the primary donor since 2001 for Africa and since 2017 for Asia.

- This collaborative initiative plays a crucial role in the effective monitoring and conservation of elephants on a global scale.

The Wildlife Trade Monitoring Network (TRAFFIC):

Founded in 1976, TRAFFIC operates at the intersection of wildlife trade, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable development. It is co-managed by WWF and IUCN.

- Headquarters: Located in Cambridge, UK.

- Mission: To ensure that the trade of wild flora and fauna does not compromise conservation efforts.

- Illegal Wildlife Trade: A major contributor to the endangerment of various species.

Governance:

TRAFFIC is overseen by a committee that includes representatives from WWF and IUCN.

- Collaboration: Engages closely with the CITES Secretariat.

- Expert Team: Comprises biologists, conservationists, researchers, communicators, and investigators, among others.

Functions of TRAFFIC:

International Treaties: Aids in the development of treaties related to wildlife trade.

Focus Areas:

Trade in tiger parts, elephant ivory, and rhino horn.

Commercial trade in timber and fisheries products.

Objectives: To achieve swift outcomes and enhance policies addressing pressing wildlife trade Challenges:

TRAFFIC India (Established in 1991): Functions as a branch of WWF-India in New Delhi, working alongside governmental bodies and agencies to address illegal wildlife trade.

Key Initiatives:

Capacity Building: Provides training for officials on wildlife law enforcement.

Research & Analysis: Conducts studies on issues such as leopard and tiger poaching, the trade of medicinal plants, bird trade, peacock feather trade, owl trade, and the dynamics of hunting communities.

Awareness Campaigns:

- “Don’t Buy Trouble” (initiated in 2008): Encourages tourists to refrain from purchasing souvenirs that could harm wildlife.

- “Wanted Alive” Series: Highlights the plight of Asian big cats—Tiger, Leopard, Snow Leopard, and Clouded Leopard—endangered by illegal trade.

International Collaboration: Instrumental in the establishment of SAWEN (South Asia Wildlife Enforcement Network) in 2011 to address wildlife crime on a regional scale.

Priority Focus Areas (Asia Pacific Regional Network):

- Community Assistance: Ensures food, water, and energy security for at-risk communities.

- Sustainability: Promotes fair access to resources, responsible land management, and effective environmental governance.

- Civil Society Involvement: Fosters support networks for sustainable development initiatives.

- Global Advocacy: Endorses international frameworks such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- Social Aspects: Concentrates on strengthening rural economies, developing social impact metrics, and advancing Green Economies.

Coalition Against Wildlife Trafficking (CAWT):

CAWT is a coalition dedicated to working together to combat the illegal trade in wildlife and wildlife products. Established in 2005, this Coalition Against Wildlife Trafficking (CAWT) is led by the United States, with India as a participating member. The founding partners of CAWT comprise:

- Conservation International

- Save the Tiger Fund

- Smithsonian Institution

- TRAFFIC International

Policies/Laws Concerning CITES in India:

The regulation of international trade concerning all wild animals and plants is governed collectively by the following legislative frameworks:

- The Wild Life (Protection) Act of 1972,

- The Foreign Trade (Development Regulation) Act of 1992,

- The Foreign Trade Policy established by the Government of India, and

- The Customs Act of 1962.

Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972:

The Act establishes a legal framework for:

- The safeguarding of wild flora and fauna and the management of their ecosystems.

- The regulation of commerce involving wild species and their products.

- The categorization of species into schedules that denote varying levels of protection.

Significant Outcomes:

- Enabled India’s accession to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

- Now extends its jurisdiction to Jammu & Kashmir following the Reorganisation Act.

Constitutional Provisions:

- The 42nd Amendment of 1976 transferred “Forests and Protection of Wild Animals and Birds” from the State List to the Concurrent List.

- Article 51A (g) outlines the fundamental duty of citizens to conserve and enhance forests and wildlife.

- Article 48A serves as a directive principle mandating states to protect the environment and wildlife.

Schedules Established by the Act:

- Schedule I: Encompasses endangered species requiring the highest level of protection (e.g., Black Buck, Snow Leopard, Asiatic Cheetah). Violations incur severe penalties, and hunting is forbidden except in cases of threats to human life or incurable diseases.

- Schedule II: Provides high protection for species such as the Assamese Macaque, Himalayan Black Bear, and Indian Cobra, with a prohibition on trade.

- Schedules III & IV: Include protected but non-endangered species (e.g., Chital, Bharal, Flamingos, Kingfishers) with lesser penalties for violations.

- Schedule V: Identifies vermin species (e.g., Crows, Rats, Mice) that may be hunted.

- Schedule VI: Governs specific plants (e.g., Blue Vanda, Slipper Orchids) with restrictions on their cultivation and trade.

Authorities Established Under the Act:

- National Board for Wildlife (NBWL): The principal authority for wildlife-related issues.

- State Board for Wildlife (SBWL): Led by the Chief Ministers of States/Union Territories.

- Central Zoo Authority: Oversees zoo regulations and manages animal transfers both nationally and internationally.

- National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA): Enhances tiger conservation efforts and designates tiger reserves.

- Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB): Addresses organized wildlife crime.

Protected Areas Defined by the Act:

Categories include Sanctuaries, National Parks, Conservation Reserves, Community Reserves, and Tiger Reserves.

Revisions to the Legislation:

- 1991 Revision: Strengthened penalties and provided protection for endangered species.

- 2002 Revision: Established community reserves and conservation reserves.

- 2006 Revision: Tackled human-wildlife conflicts and established the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and the Wildlife Crime Bureau.

2022 Revision:

Condensed the schedules to four categories:

- Schedule I (maximum protection for animals).

- Schedule II (moderate protection for animals).

- Schedule III (protection for plants).

- Schedule IV (specimens covered by CITES).

- Allowed the use of elephants for religious and other purposes.

- Enhanced penalties for infractions.

Policies Regulating Foreign Trade:

Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992:

- This legislation governs the import and export of goods, including wildlife specimens and their derivatives, in accordance with the stipulations set forth by the Government of India (GoI).

Foreign Trade Policy (2009–2014):

- This policy, periodically released by the Ministry of Commerce, specifies which wildlife and wildlife products are either restricted or allowed for import and export. It was developed in collaboration with the CITES Management Authority in India and is enforced under the Customs Act of 1962.

EXIM Policy:

Permitted Activities:

- The export and import of wild animals, plants, and their products for purposes such as research or zoo exchanges are allowed, provided they are licensed by the Director-General of Foreign Trade (DGFT).

Restrictions:

- The commercial import of African ivory is banned in accordance with CITES regulations. Additionally, any import of wildlife derivatives necessitates prior approval from the DGFT. Importing wild animals for personal use as pets must adhere to CITES guidelines.

Enforcement: Wildlife Crime Control Bureau:

Established in 2007 under the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, this organization serves as the primary agency for enforcing CITES regulations. It operates as a statutory body under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC).

Regional and Border Offices include:

- Regional Offices: Delhi (Headquarters), Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, and Jabalpur.

- Border Units: Located in Ramanathapuram, Gorakhpur, Motihari, Nathula, and Moreh.

Mandates as per the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 encompass the following:

- Intelligence Operations: Gather, organize, and share intelligence regarding organized wildlife crime with state authorities and enforcement agencies.

- Data Management: Create a centralized database for wildlife crime.

- Coordination: Facilitate the enforcement of wildlife legislation among various agencies.

- International Collaboration: Support global organizations and foreign entities in combating wildlife crime.

- Capacity Building: Provide training for agencies involved in wildlife crime enforcement.

- Prosecution Support: Assist state governments in achieving successful legal prosecutions.

- Policy Advice: Offer expert recommendations to the Government of India concerning wildlife crime issues.

Additional Functions include:

- Customs Assistance: Aid Customs officials in the inspection of flora and fauna shipments in accordance with the Wildlife Protection Act, CITES, and the EXIM Policy.

Operation Clean Art:

- Objective: This initiative marks the first nationwide effort by the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) aimed at combating the illicit trade of mongoose hair, which is utilized in the production of hairbrushes.

- Impact: The trade of 150 kg of mongoose hair results in the death of approximately 6,000 mongooses.

- Protection: All species of mongoose in India are protected under Schedule II of the Wildlife Protection Act (WPA) and listed in CITES Appendix I, which prohibits their commercial exploitation.

‘Not All Animals Migrate by Choice’ Campaign:

- Initiated By: WCCB in collaboration with UN Environment.

- Objective: The campaign seeks to enhance public awareness regarding the illegal wildlife trade and to diminish the demand for wildlife products, aligning with the UN’s global initiative, Wild for Life.

- Phase I Focus: The initial phase targets endangered species such as the Tiger (EN), Pangolin (EN), Star Tortoise (VU), and Tokay Gecko (LC).

- Phase II: Future phases will expand to include additional endangered species.

Convention on Migratory Species (CMS):

Also referred to as the Bonn Convention or the Global Wildlife Conference, this treaty was established in 1979 in Bonn, Germany, under the auspices of the UN Environment Programme and became effective in 1983.

Its importance lies in being the sole global treaty, supported by the United Nations, that focuses on the conservation of migratory species—encompassing terrestrial, aquatic, and avian life—throughout their habitats.

The treaty comprises two appendices:

- Appendix I: Identifies migratory species that are at risk of extinction, prompting member parties to implement stringent protective measures.

- Appendix II: Covers species that gain from international collaborative efforts.

The 13th Conference of the Parties to CMS (CoP13):

India has been elected as the President of the Conference of the Parties (COP) for a three-year term.

Uzbekistan will host CoP14 in 2023.

Significant Outcomes:

- New Species Included in CMS Appendices:

- A total of ten species have been added.

Seven species have been designated to Appendix I, which provides the highest level of protection. These include:

- Asian Elephant (Endangered), Great Indian Bustard (Critically Endangered), Bengal Florican (Critically Endangered), and Little Bustard (Near Threatened).

Gandhinagar Declaration:

- This declaration promotes the incorporation of ecological connectivity for migratory species within the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

Central Asian Mammals Initiative:

The Central Asian Mammals Initiative (CAMI), spearheaded by the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), seeks to protect 15 migratory mammal species along with their habitats in Central Asia. The initiative has been sanctioned for the period from 2021 to 2026 and includes the IUCN Save Our Species’ Central Asia initiative as a potential funding source for the conservation of critical threatened migratory species.

Key Species Featured in the Central Asian Mammals Initiative:

- Wild Yak (VU) – Aksai Chin

- Snow Leopard (VU) – Himalayas

- Asiatic Wild Ass / Khulan (NT) – Rann of Kutch

- Cheetah (VU) / Asiatic Cheetah (CR) – Kuno National Park, Madhya Pradesh

- Saiga Antelope (CR) – Not present in India

- Wild or Bactrian Camel (CR) – Not present in India

- Argali / Mountain Sheep (NT) – Trans-Himalayas

- Kiang / Tibetan Wild Ass (LC)

- Chiru / Tibetan Antelope (NT)

- Tibetan Gazelle (NT)

- Chinkara / Indian Gazelle (LC) – Western and Central India

- Leopard (VU) – Forested areas at elevations below 2,500 meters

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN):

IUCN is a global non-governmental organization dedicated to nature conservation and the sustainable management of natural resources. Its main office is located in Gland, Switzerland. The organization engages in various activities, including research, field initiatives, advocacy, lobbying, and educational efforts. IUCN is particularly recognized for its compilation and publication of the IUCN Red List, which evaluates the conservation status of species across the globe.

IUCN Red List or Red Data List or Red Book:

Founded in 1964, this resource serves as the most extensive catalog of global conservation statuses for biological species.

Classification: The designation “threatened” encompasses species categorized as:

Critically Endangered, Endangered, and Vulnerable.

Sections in the Publication:

- Pink Pages: Document species identified as Critically Endangered.

- The quantity of pink pages has been steadily increasing over time.

- Green Pages: Feature species that have successfully recovered and are no longer deemed threatened.

The IUCN Red List is essential for informing global conservation initiatives by tracking the status and recovery of various species.

Critically Endangered (CR):

- This status is characterized by a significant decline in population, specifically a reduction exceeding 90% over the past decade.

- Additionally, the population size is typically fewer than 50 mature individuals, although this criterion is not always strictly enforced, as many species classified as CR may have populations greater than 50.

- Furthermore, there is at least a 50% likelihood of extinction in the wild within the next 10 years.

BirdLife International (BI):

The largest global partnership dedicated to nature conservation comprises 120 national organizations across the world.

Objective: To protect avian species, their ecosystems, and overall biodiversity, while advocating for the sustainable management of natural resources.

Functions:

- Serves as the official authority for the Red List of birds as recognized by the IUCN.

- Identifies Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs), which are crucial locations for the conservation of threatened or migratory bird species.

IBAs:

- Worldwide: More than 13,000 IBAs have been recognized globally.

- In India: BirdLife International (BI) and the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), BI’s partner in India, have pinpointed 554 IBAs throughout the nation.

- BI plays a vital role in the global initiatives for bird conservation and sustainable development.

Tiger Conservation and Project Tiger:

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the worldwide population of tigers has plummeted from approximately 100,000 to under 4,000. In 2006, the number of tigers in India reached a historic low of 1,411, with the tigers in the Sariska reserve in Rajasthan completely vanishing. However, following 2006, significant conservation initiatives undertaken by India resulted in a gradual rise in the tiger population.

Challenges to Tiger Conservation:

- Habitat Degradation and Fragmentation: Large-scale development initiatives, including the construction of dams, industrial facilities, mining operations, and railway systems, result in significant habitat loss and fragmentation, which adversely affects tiger populations.

- Effects of Invasive Species: Invasive species can disrupt local ecosystems, beginning with native producers and leading to a ripple effect throughout the food web. As apex predators, tigers are particularly vulnerable to these changes. Their role as “Umbrella Species” underscores their importance for maintaining ecosystem health.

- Poaching and Illegal Wildlife Trade: Tigers are frequently hunted for their body parts, which are often utilized in traditional medicine, posing a continuous threat to their existence.

- Market Demand for Tiger Products: Efforts to curtail the demand for products derived from tigers have encountered numerous obstacles, further intensifying the issue of poaching.

- Restoration of Tiger Populations: Outside of India, Nepal, and Russia, many countries face significant challenges in their attempts to revive declining tiger populations.

- Risk of Canine Distemper Virus (CDV): The Canine Distemper Virus can be transmitted from infected domestic dogs in proximity to wildlife reserves, affecting the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and nervous systems. This disease represents a considerable threat to wildlife, as evidenced by its detrimental effects on lion populations in the Gir forest.

- Preventive Strategies: It is crucial to implement proactive vaccination programs for both free-ranging and domestic dogs in regions adjacent to national parks, as managing diseases within wildlife populations remains a complex challenge.

Actions Undertaken by the Government of India:

Legal Framework:

- The Wild Life (Protection) Act was revised from its original 1972 version to the updated 2006 legislation. This amendment led to the formation of the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB).

- Additionally, it introduced stricter penalties for violations occurring within tiger reserves and core areas.

Administrative Measures:

- Efforts to combat poaching have been intensified, including the implementation of specialized patrolling strategies during the monsoon season.

- State-level Steering Committees, led by Chief Ministers, and Tiger Conservation Foundations have been established to oversee conservation efforts.

- Furthermore, the Special Tiger Protection Force (STPF) was created to enhance protection measures.

Financial Initiatives:

- The government has allocated financial and technical support to states through Centrally Sponsored Schemes, which include Project Tiger and the Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats.

- Three-Pronged Approach to Address Human-Wildlife Conflict: Material and Logistical Assistance: Funding from Project Tiger is utilized to provide necessary resources.

- Limiting Habitat Interventions: Interventions are restricted based on the carrying capacity of tiger reserves to reduce the likelihood of conflicts.

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): The NTCA has issued guidelines for effectively managing human-wildlife conflicts.

International Collaboration:

- Bilateral Agreements: India and Nepal have established agreements to combat cross-border illegal wildlife trade.

- Protocols have also been signed with Bangladesh and China to enhance tiger conservation efforts.

- Conservation Sub-Group: Collaborative initiatives with Russia focus on the conservation of tigers and leopards.

- Global Tiger Forum (GTF): Founded in 1994 and based in New Delhi, the GTF advocates for international campaigns aimed at the conservation of tigers, their prey, and their habitats.

- CITES Compliance: As a signatory to CITES, India complies with the significant resolution that bans the breeding of tigers for the purpose of trading their parts and derivatives.

Project Tiger (PT):

- Population Decline: By the conclusion of the 20th century, the number of tigers plummeted significantly from an estimated 20,000–40,000 to approximately 1,800 individuals, as recorded in the 1972 census.

- Initiation: Launched in 1973 at Jim Corbett National Park in Uttarakhand, the project aims to safeguard tigers and maintain a sustainable population within their natural environments.

- Core-Buffer Strategy: The tiger reserves established under this strategy operate within the framework of PT (1973), a Centrally Sponsored Scheme overseen by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) and managed by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA).

Key Initiatives:

- Relocation of local communities to mitigate human-tiger conflicts.

- Formation of the Tiger Protection Force to address poaching issues.

Tiger Task Force:

- Objective: The recommendations from the National Board for Wildlife highlighted the necessity for a statutory body dedicated to tiger conservation.

- Primary Recommendations: Enhance Project Tiger by providing it with legal and administrative support to effectively tackle conservation challenges.

National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA):

Established: Formed under the Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act of 2006.

Purpose:

- To manage Project Tiger as a statutory entity under the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF).

- To collaborate with the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) in the fight against wildlife offenses.

Governance:

- Manages tiger reserves through field directors in accordance with the guidelines set by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA).

- Any changes to the boundaries of tiger reserves or their de-notification must receive approval from both the NTCA and the National Board for Wildlife.

NTCA Members:

Led by the Minister for Environment and Forests.

Comprises:

- Eight specialists in wildlife conservation and tribal welfare.

- Three Members of Parliament.

- The Inspector-General of Forests, who serves as the ex-officio Member Secretary.

- Other representatives.

Functions of NTCA:

- Develops standards and guidelines for the conservation of tigers in reserves, parks, and sanctuaries.

- Compiles Annual and Audit Reports for submission to Parliament.

State-Level Mandates:

- State Steering Committees: Chaired by Chief Ministers to oversee tiger protection, monitoring, and coordination efforts.

- Tiger Conservation Plans: Promoted at the state level, in conjunction with Tiger Conservation Foundations.

Challenges:

- Forest Rights Act (2006): The acknowledgment of the rights of forest-dwelling communities has sparked discussions regarding its effects on Project Tiger.

- Habitat Saturation: The limited availability of green cover often leads to early saturation points for tiger populations, hindering their growth.

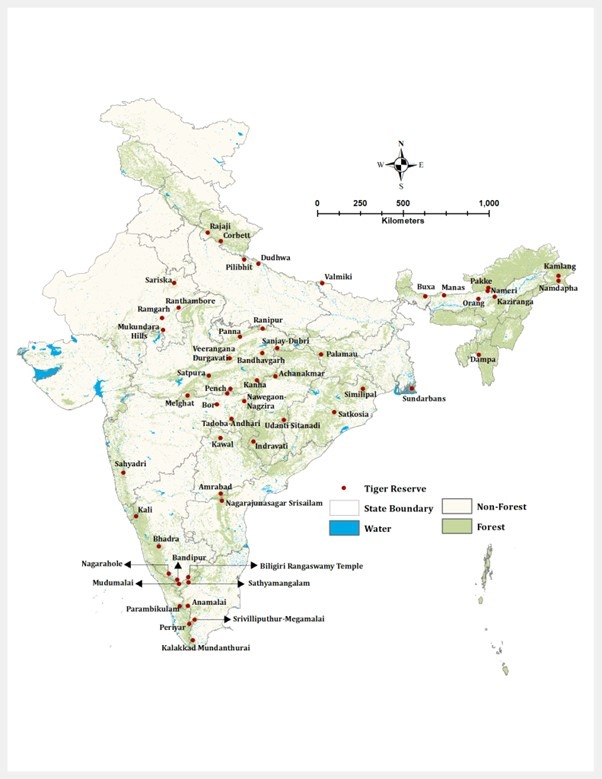

Tiger Corridors:

The NTCA, in collaboration with the Wildlife Institute of India, has mapped 32 major tiger corridors across the country to connect tiger populations. These corridors are classified into four landscapes:

1. Shivalik Hills & Gangetic Plains:

- Rajaji-Corbett (Uttarakhand)

- Corbett-Dudhwa (Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Nepal)

- Dudhwa-Kishanpur-Katerniaghat (Uttar Pradesh, Nepal)

2. Central India & Eastern Ghats:

- Ranthambhore-Kuno-Madhav (Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan)

- Bandhavgarh-Achanakmar (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh)

- Bandhavgarh-Sanjay Dubri-Guru Ghasidas (Madhya Pradesh)

- Guru Ghasidas-Palamau-Lawalong (Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand)

- Kanha-Achanakmar (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh)

- Kanha-Pench (Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra)

- Pench-Satpura-Melghat (Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra)

- Kanha-Navegaon Nagzira-Tadoba-Indravati (MP, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh)

- Indravati-Udanti Sitanadi-Sunabeda (Chhattisgarh, Odisha)

- Similipal-Satkosia (Odisha)

- Nagarjunasagar-Sri Venkateshwara NP (Andhra Pradesh)

3. Western Ghats:

- Sahyadri-Radhanagari-Goa (Maharashtra, Goa)

- Dandeli Anshi-Shravathi Valley (Karnataka)

- Kudremukh-Bhadra (Karnataka)

- Nagarahole-Pushpagiri-Talakavery (Karnataka)

- Nagarahole-Bandipur-Mudumalai-Wayanad (Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu)

- Parambikulam-Eravikulam-Indira Gandhi (Kerala, Tamil Nadu)

- Kalakad Mundanthurai-Periyar (Kerala, Tamil Nadu)

4. North East:

- Kaziranga-Itanagar WLS (Assam, Arunachal Pradesh)

- Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong (Assam)

- Kaziranga-Nameri (Assam)

- Kaziranga-Orang (Assam)

- Kaziranga-Papum Pare (Assam)

- Manas-Buxa (Assam, West Bengal, Bhutan)

- Pakke-Nameri-Sonai Rupai-Manas (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam)

- Dibru Saikhowa-D’Ering-Mehao (Assam, Arunachal Pradesh)

- Kamlang-Kane-Tale Valley (Arunachal Pradesh)

- Buxa-Jaldapara (West Bengal)

Core and Buffer Zones in Tiger Reserves:

Core Area:

- Core areas are designated by State Governments in collaboration with an Expert Committee and are subject to strict protection, prohibiting any human activities.

- Legal Status: These areas hold the same legal standing as national parks or wildlife sanctuaries, where activities such as the collection of minor forest products, grazing, and any form of human disturbance are not allowed.

- Tribal Case: The Soligas, a tribal community from Chamarajnagar in Karnataka, were the first to have their forest rights acknowledged within a core area. They reside in the forests of Biligiri Rangana Hills (BR Hills) and Male Mahadeshwara Hills, coexisting with nature without adversely affecting the tiger population.

- Timeline: In 1974, BR Hills was designated as a Wildlife Sanctuary, leading to the eviction and relocation of the Soligas. By 2011, it was established as a Tiger Reserve, which imposed further restrictions on access to forest resources.

- Special Note: Although uncommon, this recognition serves as an example of positive human-wildlife interactions in specific contexts.

Buffer Area:

- The buffer area encircles the core area, serving as a habitat for dispersing tigers while permitting limited human activities to promote coexistence.

- Tribal Rights: Under the Forest Rights Act (2006), tribal rights are acknowledged, allowing for the sustainable collection of minor forest products and grazing.

- Decision Process: The boundaries of these zones are determined by the Gram Sabha in conjunction with an Expert Committee.

- These buffer zones are designed to facilitate conservation efforts while carefully managing human-tiger interactions, taking into account the needs of local communities. Cases like that of the Soligas exemplify the significant impact of judicial interventions in recognizing tribal rights.

Tiger Census:

- Frequency: The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) conduct this census every four years.

- 2014 Census: This census marked the first estimation of the leopard population in India, approximating around 11,000 individuals.

- Estimation Techniques

- Pugmark Census: This method was previously employed to identify individual tigers and their sex through pugmark imprints. It is now utilized as an indicator of tiger presence and population density.

- Camera Trapping: This technique distinguishes tigers by analyzing their unique stripe patterns captured in photographs.

- DNA Fingerprinting: This method identifies tigers through genetic material obtained from their feces.

2018 Census Methodology:

- Method: The census employed a double sampling approach, integrating ground surveys with camera traps.

- Phases 1 & 2: During these phases, signs such as scat and pugmarks were collected through surveys.

- Phase 3: The collected data was mapped using Geographic Information System (GIS) technology and remote sensing.

- Phase 4: Data was extrapolated for regions lacking camera coverage.

- Coverage: Camera traps successfully captured individual photographs of 83% of the tiger population.

MSTrIPES – Monitoring System for Tiger Protection

Launch: Initiated in 2010 within Indian tiger reserves by the NTCA and WII.

Components:

- Field protocols for patrolling, law enforcement, wildlife crime documentation, and ecological monitoring.

- GIS software for data management, analysis, and reporting.

- Role of Forest Guards: Forest guards are responsible for recording patrolling routes using GPS, uploading observations, and geo-tagging images into the GIS database.

Advantages of MSTrIPES:

- Facilitates real-time identification of deficiencies in patrolling efforts.

- Serves as documentation of the presence and activities of forest guards in designated areas.

2022 Tiger Census Report (All-India Tiger Estimate):

International Big Cat Alliance (IBCA):

- Objective: To conserve seven species of big cats: Tiger, Lion, Leopard, Snow Leopard, Cheetah, Jaguar, and Puma.

- Membership: Comprises 97 countries where these species are native, along with various stakeholders.

Primary Focus Areas:

- Advocacy and collaboration.

- Capacity enhancement for conservation efforts.

- Promotion of eco-tourism and sustainable funding.

- Dissemination of information and raising public awareness.

Highlights from India’s 5th Tiger Census (2022) :

Population Trends:

- The tiger population rose to 3,682 in 2022 (revised from 3,167), up from 2,967 in 2018, reflecting an increase of 200.

- Growth Rate: The annual growth rate has decreased to 6.1% from 2018 to 2022, compared to a previous rate of 33% from 2014 to 2018.

Regional Observations:

- Increases: The Shivalik Hills, Gangetic Plains, and Central India have shown population growth.

- Declines: States such as Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Telangana, and the Western Ghats have reported declines.

- There has been a notable loss of occupancy in Wayanad and Biligiriranga Hills.

Significant Tiger Clusters:

- North East Hills and Brahmaputra Plains: 194 tigers were documented using camera traps.

- Nigiri Cluster: Home to the largest tiger population globally, facilitating nearby colonization.

- High Priority: The protection of Simlipal’s small, genetically distinct tiger population is crucial.

Methodology:

- The census covered 20 states, employing 32,588 camera traps and capturing 47 million images.

- It integrates ground surveys, GIS mapping, and extrapolated data analysis.

Conservation Insights:

- The initiative advocates for ecologically sustainable development.

- It encourages trans-boundary conservation efforts for isolated tiger populations.

Key States & Reserves:

Leading States:

- Madhya Pradesh (785 tigers)

- Karnataka (563)

- Uttarakhand (560)

- Maharashtra (444)

Top Reserves:

- Corbett National Park (260 tigers)

- Bandipur (150)

- Nagarhole (141)

- Bandhavgarh (135)

- Dudhwa (135)

International Efforts Towards Tiger and Snow Leopard Conservation:

The Global Tiger Initiative:

The Global Tiger Initiative (GTI) was established in 2008 as a collaborative effort among governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil society, and scientific communities, aimed at preventing the extinction of wild tigers. In 2013, the initiative expanded its focus to include Snow Leopards, classified as Vulnerable (VU).

The founding partners of the GTI comprise:

- the World Bank,

- the Global Environment Facility (GEF),

- the Smithsonian Institution, recognized as the largest museum, education, and research complex globally,

- the Save the Tiger Fund, which supported tiger conservation projects in Asia from 1995 to 2011, and

- the International Tiger Coalition, which represents over 40 NGOs.

Leadership of the GTI is provided by the 13 countries that are home to tiger populations: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Program (GSLESP):

In 2013, the Global Tiger Initiative expanded its focus to encompass Snow Leopards. The member nations endorsed the Bishkek Declaration, which encourages collaboration among members to identify and protect a minimum of 20 snow leopard habitats throughout the species’ range by the year 2020, encapsulated in the phrase “Secure 20 by 2020.”

The membership comprises the following nations:

- Kyrgyzstan

- Afghanistan

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Pakistan

- Thirteen countries that are part of the Tiger Range.

Assessment of Snow Leopard Populations in India:

The assessment of snow leopard populations in India was initiated at the 4th steering committee meeting of the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection (GSLEP) program. This initiative is part of the broader Population Assessment of the World’s Snow Leopard (PWAS) project, also spearheaded by GSLEP. Notably, this marks the first instance in which India will implement a national protocol for estimating the population of snow leopards.

St. Petersburg Declaration:

Adopted in 2010 during the International Tiger Conservation Forum in St. Petersburg, Russia, the initiative was endorsed by the governments of the 13 Tiger Range Countries (TRCs): Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Objectives and Framework: The primary objective, known as TX2, aimed to increase the global wild tiger population from approximately 3,200 to over 7,000 by the year 2022.

The declaration highlighted several key points:

- The necessity for coordinated and comprehensive conservation efforts across the TRCs.

- The importance of securing sustainable funding for tiger recovery initiatives.

- The establishment of the Global Tiger Recovery Program (GTRP) as the implementation framework.

Achievements:

Countries such as India, Nepal, and Russia have illustrated that tiger population recovery is feasible:

- India raised its tiger count from 1,706 in 2010 to 2,226 in 2015.

- Nepal and Russia have also reported encouraging outcomes from their conservation efforts.

Obstacles:

However, the global tiger population did not meet the TX2 target:

- According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), there are currently only about 3,900 wild tigers remaining worldwide.

- Southeast Asia has faced significant challenges, with tiger populations continuing to decline despite ongoing conservation measures.

Importance:

The St. Petersburg Declaration represented the first global commitment to tiger recovery, underscoring the need for collaboration and innovative approaches. Although progress has been inconsistent, it laid the groundwork for future conservation efforts aimed at protecting tigers.

International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime:

The International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC) was founded in 2010 during the Tiger Forum Meeting held in St. Petersburg. Its primary objective is to enhance criminal justice systems and offer coordinated assistance at national, regional, and international levels to address wildlife crime effectively.

The ICCWC collaborates with several partner organizations, including the CITES Secretariat, INTERPOL, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the World Bank, and the World Customs Organization (WCO).

TX2 and Tiger Conservation Excellence Award:

TX2 Initiative: A worldwide effort aimed at increasing the wild tiger population by 2022, with India participating in the WWF-led agreement.

Conservation Assured | Tiger Standards (CA|TS):

- Established in 2013, these criteria assess tiger conservation initiatives at various sites.

- The WWF facilitates the implementation of these standards across countries that are home to tigers.

- In India, 17 Tiger Reserves have achieved international CA|TS accreditation.

TX2 Award: This award is given to locations that have demonstrated remarkable growth in tiger populations since 2010.

2020 Recipient: Pilibhit Tiger Reserve.

Tiger Conservation Excellence Award

This accolade recognizes sites that excel in at least two of the following areas:

- Monitoring of tiger and prey populations (including translocation and prey enhancement).

- Effective management of the site (as per CA|TS evaluations).

- Strengthened law enforcement measures.

- Community-driven conservation and conflict resolution.

- Management of habitat and prey.

2020 Recipient: Transboundary Manas Conservation Area (located on the India-Bhutan border), which includes:

- Manas National Park (500 km², Assam).

- Royal Manas National Park (1,057 km², Bhutan).

Declarations Supporting Wildlife Conservation:

- Gandhinagar Declaration: Emphasizes the significance of ecological connectivity and migratory species within the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

- Bishkek Declaration: Establishes the “Secure 20 by 2020” objective to protect at least 20 snow leopard landscapes worldwide as part of the GSLESP initiative.

- Petersburg Declaration: Initiated the T2 Program, aiming to double global tiger populations under the Global Tiger Recovery Program (GTRP).

Project Snow Leopard:

Initiated in 2009, this initiative aims to protect India’s wildlife and habitats located at high altitudes.

Conservation Areas:

- Hemis-Spiti (Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh)

- Nanda Devi-Gangotri (Uttarakhand)

- Khangchendzonga-Tawang (Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh)

Global Conservation Acknowledgment:

In 2003, the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) designated the Snow Leopard as a Concerted Action Species under Appendix I. Additionally, in the same year, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) broadened the scope of the Tiger Enforcement Task Force to include all Asian big cats, encompassing Snow Leopards.

Significance of High-Altitude Ecosystems (above 3000m):

Key Fauna:

Threatened Species:

- Snow Leopard (Vulnerable), Red Panda (Endangered), two Musk Deer species (Endangered), and Hangul/Kashmir Stag (Critically Endangered).

Mountain Ungulates:

- Wild Yak (Vulnerable), Chiru (Near Threatened), Tibetan Gazelle (Near Threatened), Tibetan Argali (Near Threatened), Ladakh Urial (Vulnerable), Himalayan Goral (Near Threatened), Serow (Vulnerable), Takin (Vulnerable).

Birdlife:

- Black-Necked Crane (Near Threatened), Bar-Headed Geese (Least Concern).

Distinctive Characteristics:

- High-altitude lakes and wetlands are vital breeding sites for bird species. These regions sustain delicate biodiversity and host species that have adapted to harsh climatic conditions.

Reintroduction of Cheetahs in India:

Historical Milestone: After a period of 70 years without their presence, eight cheetahs (comprising five females and three males) were successfully reintroduced from Namibia to Kuno Palpur National Park in Madhya Pradesh, which spans 748 square kilometers. This event marks the first instance of intercontinental translocation of a carnivore species into an unfenced protected area globally.

Significance: In contrast to South Africa’s approach of fortress conservation, which involves fully fenced protected areas that exclude local communities, India’s buffer zones permit neighboring populations to utilize resources sustainably, thereby fostering a harmonious coexistence. This strategy is favored by social scientists.

Ecological Impact: Role of Cheetahs: The reintroduction of cheetahs is anticipated to aid in the restoration of open forests and grasslands, thereby establishing India as a habitat for four species of wildcats: the Tiger, Lion, Leopard, and Cheetah.

Monitoring Task Force: Duration: A two-year period will be dedicated to overseeing the health of the cheetahs, managing quarantine enclosures, and ensuring the suitability of open habitats. Eco-tourism Focus: The task force will provide guidance on developing tourism infrastructure within Kuno National Park and other protected areas, thereby enhancing conservation efforts and promoting community involvement.

Cheetah vs Leopard vs Jaguar:

African Cheetah versus Asiatic Cheetah

IUCN Status:

- African Cheetah: Classified as Vulnerable.

- Asiatic Cheetah: Classified as Critically Endangered.

- CITES Listing: Both species are included in Appendix-I.

Population:

- African Cheetah: Estimated population of approximately 6,500 to 7,000 individuals distributed throughout Africa.

- Asiatic Cheetah: A mere 40 to 50 individuals remain, confined to Iran, with the species having been declared extinct in India since 1952.

Physical Characteristics:

- African Cheetah: Exhibits a larger physique in comparison to the Asiatic Cheetah.

- Asiatic Cheetah: Characterized by a smaller size, lighter coloration, distinctive red eyes, and a feline-like appearance.

Why Kuno NP?

Habitat Considerations:

- Importance of Space: Although cheetahs do not target humans or large livestock as prey, adequate space is crucial for their survival.

- Appropriate Habitat: With the exception of high-altitude regions, coastal areas, and the northeastern part of the country, the majority of India is recognized as suitable habitat for cheetahs.

- Selection of Kuno: Kuno has been identified as the most favorable site based on evaluations conducted by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI). These assessments considered climatic factors, prey availability, the presence of competing predators, and the historical distribution of cheetahs.

Distinctive Characteristics of Kuno:

- Human Relocation: Approximately 24 villages and their livestock were relocated years ago, resulting in the absence of human settlements within the park.

- Savannah Ecosystem: The areas where villages once stood and agricultural activities took place are now dominated by grasses, providing optimal conditions for cheetah habitation.

- Historical Habitat: Kuno is situated near the Sal forests of Chhattisgarh, which is part of the cheetah’s historical range.

- Potential for Coexistence: Kuno presents a unique opportunity to accommodate all four major Indian big cats—tiger, lion, leopard, and cheetah. Initially, it was suggested as a secondary habitat for Asiatic lions.

Challenges:

Leopard Population:

- The substantial population of leopards in Kuno presents significant challenges.

- Leopards possess greater strength and a wider habitat range, thriving in both forests and grasslands, whereas cheetahs primarily depend on open grasslands.

- The adaptability of leopards may lead to competition with cheetahs in overlapping territories.

- This initiative underscores the intricate nature of balancing species reintroduction, ecological needs, and predator coexistence.

Conservation of Lions:

Asiatic Lion:

Geographical Range: The Asiatic Lion is found solely in India, predominantly within the confines of Gir National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary in Gujarat, which serves as the last bastion for this species. Historically, its range extended across West Asia, the Middle East, West Bengal, and Central India.

Conservation Status:

- IUCN Red List: Endangered (EN).

- CITES: Appendix I.

- WPA: Schedule I.

Project Lion:

Aim: To implement conservation strategies based on landscape ecology, incorporating eco-development initiatives within the Gir ecosystem.

Primary Objectives:

- Safeguard and rehabilitate lion habitats.

- Effectively manage the increasing lion populations.

- Encourage community involvement and enhance local livelihoods.

Population Trends:

The population of Asiatic Lions rose to 674 in 2020, reflecting a 28.87% increase from 523 in 2015.

Leopard Population in India:

2020 Estimate: The leopard population was estimated at 12,852, marking a 60% rise from 7,910 in 2014, indicative of successful conservation measures.

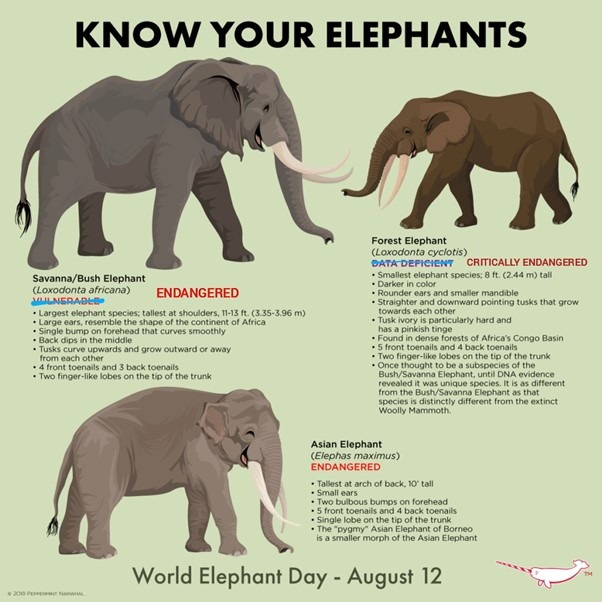

Conservation of Elephants:

Population: India is home to more than 60% of the world’s Asian elephant population. Although their numbers have largely remained stable, the pressure on their habitats due to human activities presents a significant threat.

Conservation Status:

- Asian elephants are classified under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act (WPA), which provides them with the highest level of legal protection.

Challenges to Asian Elephant Conservation:

- Habitat Pressure: The expansion of human activities and alterations in land use are endangering their natural habitats.

- Poaching: While the threat of ivory poaching is less pronounced for Asian elephants—since only males possess tusks—it continues to be a matter of concern.

African Elephants: A Comparative Perspective:

Both Males and Females Possess Tusks: This characteristic increases their susceptibility to ivory poaching.

Conservation Status:

- African Forest Elephant: Classified as Critically Endangered (CR).

- Reproductive Challenge: African Forest Elephants experience an extended gestation period of nearly 22 months, the longest of any mammal, which complicates conservation initiatives.

Asian Elephant vs African Elephant and African Forest Elephant vs African Savanna (Bush) Elephant:

African Forest Elephant:

- Habitat: Tropical woodlands located in Central and Western Africa.

- Physical Characteristic: Tusks that extend downward.

Conservation Status:

- IUCN Red List: Critically Endangered (CR).

African Savannah (Bush) Elephant:

- Habitat: Grasslands and semi-arid areas in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Physical Characteristic: Tusks that curve outward.

Conservation Status:

- IUCN Red List: Endangered (EN).

- Distinctive Feature: Recognized as the largest terrestrial animal currently living.

Ecological Importance of Elephants:

Designated as the National Heritage Animal of India in 2010.

- Ecological Significance: The nomadic nature of elephants creates a protective umbrella effect, preserving extensive habitats that are conducive to a variety of plant and animal species.

- Ecosystem Contributions

- Landscape Modifiers: Elephants facilitate the creation of clearings within forests, which helps to control overgrowth and encourages the regeneration of plant life, ultimately benefiting other species.

- Seed Distribution: During their migratory journeys, elephants contribute to plant reproduction by dispersing seeds through their feces.

- Soil Enrichment: The dung of elephants enhances soil quality, promotes plant growth, and provides a habitat for various insects.

- Water Availability: In times of drought, elephants excavate holes to reach water sources, which in turn supports other wildlife. Their footprints also serve to collect rainwater, aiding smaller organisms.

- Food Web Dynamics: While apex predators such as tigers may occasionally prey on young elephant calves, the remains of deceased elephants offer sustenance to scavengers and other wildlife.

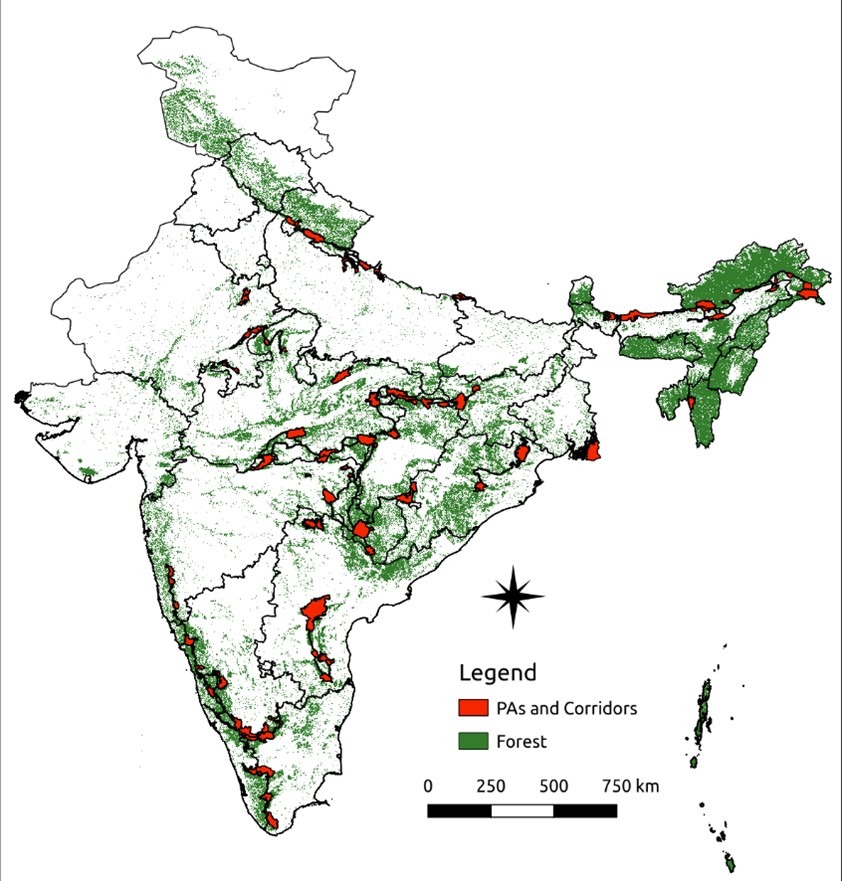

Elephant Corridor:

- These are linear and narrow natural habitat connections that facilitate the movement of elephants between secure regions without human interference.

- Study: The “Right of Passage” research, carried out by the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) in partnership with Project Elephant, has identified 101 corridors throughout India.

- Regional Distribution: The corridors are primarily located in northeastern India, followed by regions in southern India, central India, northern West Bengal, and northwestern India.

Threats to Elephant Corridors:

- Habitat Loss: This is primarily driven by fragmentation and destruction resulting from:

- Development activities such as mining, tourism, road and railway construction, and the installation of electrified fencing.

- In central and eastern India, coal and iron ore mining pose significant threats.

Human-Elephant Conflict:

- Due to limited protected areas, elephants frequently venture outside reserves in search of grazing, which leads to conflicts.

- Each year, approximately 400 human fatalities occur, along with significant losses in crops and property.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Corridor Integration: Where feasible, integrate corridors with adjacent protected areas.

- Habitat Preservation: Mitigate further fragmentation by managing encroachment from urban development.

- Legal Protection: Designate corridors as Ecologically Sensitive Areas or conservation reserves.

Community Engagement:

- Raise awareness and educate local communities.

- Promote voluntary relocation from conflict-prone areas to safer locations.

Project Elephant:

The Project Elephant initiative, funded by the central government, was established in 1992 with the aim of preserving elephant populations within their natural environments. The scheme’s objectives encompass the following:

- Providing support to states that are home to wild elephant populations.

- Ensuring the sustainable survival of recognized viable elephant populations in their natural habitats.

- Mitigating human-wildlife conflicts.

- Formulating scientific and strategic management practices for elephant conservation.

- Safeguarding elephants from poaching, curbing illegal ivory trafficking, and addressing other unnatural threats to their survival.

Other Initiatives:

Haathi Mere Saathi Campaign:

- Initiated by: The Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) in collaboration with the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) during the “Elephant-8” Ministerial Meeting held in Delhi in 2011.

- E-8 Nations: India, Botswana, Republic of Congo, Indonesia, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand.

- Aim: To enhance public understanding and foster a harmonious relationship between humans and elephants.

Project RE-HAB (Reducing Elephant-Human Conflicts):

- Launched by: The Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC).

- Primary Approach: Implementing bee boxes as barriers to prevent elephants from encroaching on human settlements. Elephants tend to avoid areas with bees due to their aversion to stings and the disturbance caused by buzzing.

- Achievements: This strategy has proven successful in the Kodagu district of Karnataka and is planned for expansion to states such as West Bengal, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Assam, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala.

Asian Elephant Alliance:

Collaboration with NGOs:

- Elephant Family

- International Fund for Animal Welfare

- IUCN

- Wildlife Trust of India

- World Land Trust

Objective: To secure 96 out of 101 elephant corridors across twelve Indian states.

IUCN Asian Elephant Specialist Group (AsESG):

Focus: A global network operating under the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of IUCN, dedicated to the research and conservation of Asian elephants.

Key Contributions:

- Provides scientific data regarding the population, distribution, and demographic conditions of elephants across thirteen range states: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- Publishes “Gajah,” a biannual journal focused on the conservation of Asian elephants.

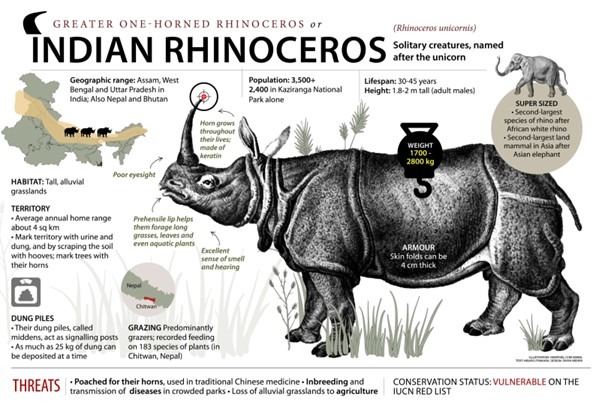

Conservation of Great One-Horned Rhinos:

Rhinos are hunted for their horns, which are made of keratin, a substance akin to human hair and nails, and are utilized in traditional medicine practices across Southeast Asia.

Rhino Species Across the World:

- White and Black Rhinos are native to Africa, with the Black Rhino being the smaller species.

- The Javan Rhino is critically endangered, with only a handful remaining in Java and Vietnam.

- The Sumatran Rhino, recognized as the smallest rhinoceros species, has an estimated population of 30 to 80 individuals, primarily located on the Indonesian island of Sumatra.

- The Great One-Horned Rhino, which is exclusively found in India, is the largest among the rhinoceros species, second only to the Asian elephant in size.

- Currently, approximately 24,500 rhinos exist in the wild, with over two-thirds of this population being white rhinos.

- African and Sumatran rhinos possess two horns, whereas the Indian and Javan rhinos have a single horn; notably, both male and female Indian rhinos have a horn.

India’s Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros:

- Habitat: Tropical and Subtropical Savannas and Shrublands.

- Distribution: Historically, Indian rhinos inhabited the northern regions of the Indian subcontinent. Currently, their range is limited to the Terai alluvial grasslands found in India, Bhutan, and Nepal.

- Populations: Notable populations exist in Kaziranga National Park, Manas National Park, and Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary.

- Threats: The species faces significant threats from poaching for its horn, loss and fragmentation of habitat, and conflicts with humans.

- IUCN Red List: Vulnerable | CITES: Appendix I | WPA: Schedule I

Conservation Initiatives:

- In 2005, Assam initiated the Indian Rhino Vision (IRV) 2020 program in collaboration with WWF India and the International Rhino Foundation, aiming for significant advancements in rhino conservation. The New Delhi Declaration on Asian Rhinos was established in 2019, focusing on the preservation and safeguarding of the species, with the participation of five rhino range countries: India, Bhutan, Nepal, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

- The Government of India commenced a project to develop DNA profiles for all rhinos.

- In 2019, the National Rhino Conservation Strategy was introduced to enhance the conservation efforts for the Indian Rhino.

India Rhino Vision (IRV) 2020:

- Objective: To establish a wild population of 3,000 Greater One-Horned Rhinos across seven protected regions in Assam by the year 2020.

- Initiative: A collaborative effort involving conservationists, the Bodoland Territorial Council, and the Assam Government, initiated in 2005.

Key Features:

- Concentrated Risks in Kaziranga: The high density of rhinos has made them susceptible to diseases, flooding, and poaching threats.

- Translocations: A fundamental aspect of the IRV 2020 initiative, this process involves relocating rhinos from Kaziranga National Park and Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary to designated habitats:

- Manas National Park: The primary site for translocation.

- Dibru Saikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary and Laokhowa-Bura Chapori Wildlife Sanctuary.

Outcomes:

- Population Goal: Successfully reached a population of 3,000 rhinos in Assam.

- UNESCO Status: Manas National Park regained its designation as a World Heritage Site due to a sustainable rhino population.

Challenges:

Efforts to expand rhino populations beyond Kaziranga, Orang National Park, and Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary were unsuccessful.

New sites faced vulnerabilities due to:

- Poaching activities.

- Inadequate monitoring of animal health.

- Tourism and infrastructure developments, such as road construction along the Indo-Bhutan border.

Recommendations for Future:

- Broaden search areas to encompass Pobitora and Amchang Wildlife Sanctuary.

- Designate the Brahmaputra river channel (Kaziranga–Orang) as a rhino conservation zone to bolster protection efforts.

Conservation of Indian Dolphins:

Indian Dolphin Species:

South Asian River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica)

The South Asian River Dolphin, a species of freshwater dolphin, is categorized into two subspecies:

- Ganges River Dolphin (P. g. gangetica)

- Indus River Dolphin (P. g. minor)

Geographic Range: Found in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan.

Threats: The species faces unintentional mortality due to entanglement in fishing gear, along with habitat loss and degradation caused by water development initiatives (such as barrages, high dams, and embankments), pollution from industrial waste and pesticides, municipal sewage discharge, and noise pollution from vessel traffic.

IUCN Status: Endangered (EN) | CITES: Appendix I | CMS: Appendix I | WPA: Schedule I

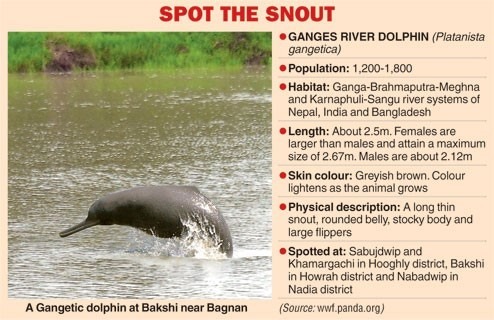

Ganges River Dolphin – Susu (P. g. gangetica):

- In 2009, the Government of India designated the Ganges River dolphin as the National Aquatic Animal. Additionally, it serves as the State Aquatic Animal of Assam.

- Due to the distinctive sound it makes while breathing, this species is commonly known as the ‘Susu’. It acts as an indicator species for the Ganga River and is exclusively adapted to freshwater environments, being essentially blind.

- The dolphin locates its prey by emitting ultrasonic sounds.

- Distribution: Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna river systems.

- The Ganges River Dolphin is the only species currently recognized under the Convention on Migratory Species.

Indus River Dolphin (P. g. minor):

- This species is recognized as the State Aquatic Animal of Punjab.

- Habitat: Found in the Indus River in Pakistan, as well as in the Beas River (the sole habitat of the Indus River Dolphin in India) and its tributaries, including the Sutlej.

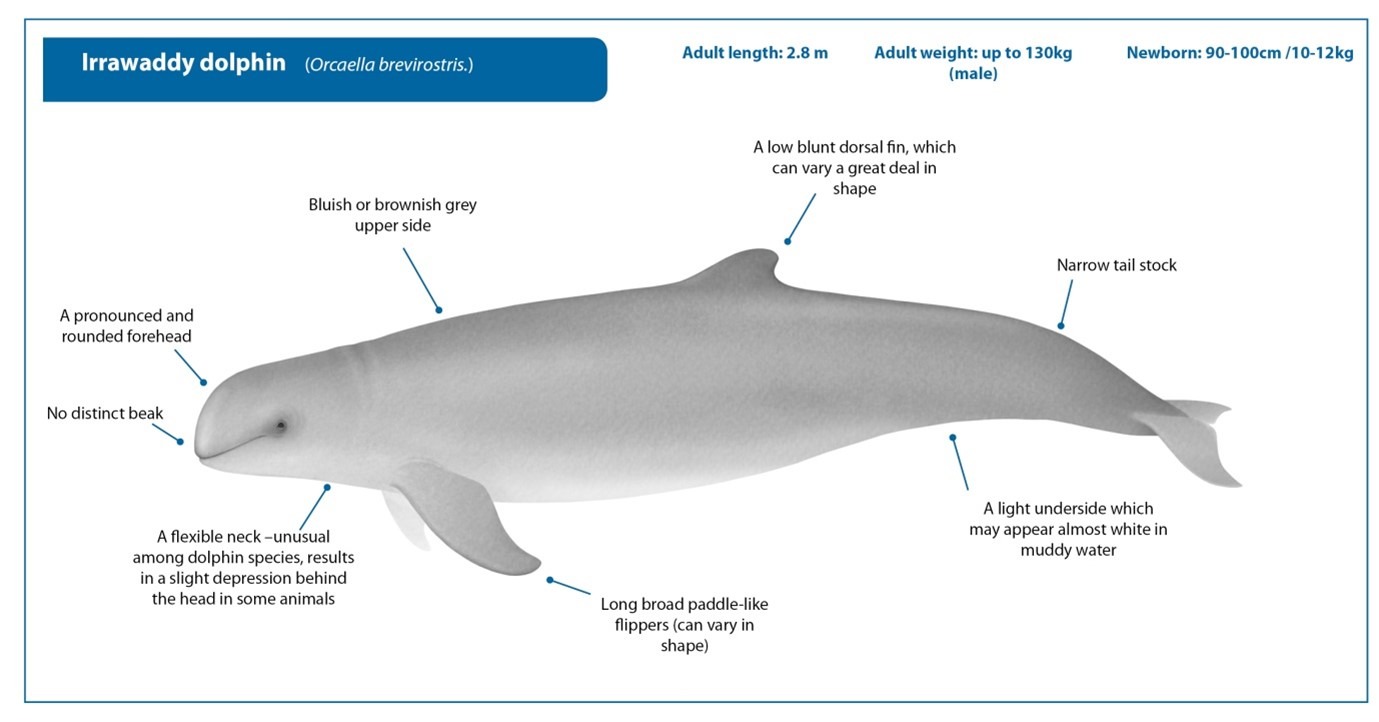

Irrawaddy Dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris):

- Habitat: This species inhabits brackish waters along coastlines, river mouths, estuaries, and freshwater rivers, notably the Ganges, Mekong, and Irrawaddy rivers.

- Distribution: Significant populations are located in lagoons, particularly in Chilika Lake, Odisha, India.

- Threats: The species faces various threats, including human-induced conflicts and accidental drowning in gillnets.

- IUCN Status: Endangered (EN) | CITES: Appendix I | CMS: Appendix I | WPA: Schedule I

Ganges River Dolphin Conservation Measures:

- Following the initiation of the Ganga Action Plan in 1985, the Government of India designated the Gangetic dolphin as a Schedule I species under the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.

- To protect their population, the National Ganga Council was established, and the Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary in Bihar was created as the sole sanctuary dedicated to dolphin conservation.

- In 2020, Prime Minister Modi announced the government’s intention to launch Project Dolphin, which received preliminary approval during the inaugural meeting of the National Ganga Council, chaired by the Prime Minister.

- This initiative aims to protect both river and marine dolphin species.

- The Conservation Action Plan for the Gangetic Dolphin (2010-2020) identified various threats to the species, including the effects of river traffic, irrigation canals, and the reduction of their prey base on dolphin populations.

- The Ganges River Dolphin is recognized as one of 21 species under the Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitat program.

- In 2009, during the first meeting of the National Ganga River Basin Authority, the then Prime Minister proclaimed the Gangetic River dolphin as the national aquatic animal.

- The National Mission for Clean Ganga, which oversees the government’s flagship initiative Namami Gange, commemorates October 5 as National Ganga River Dolphin Day.

Conservation of India Crocodile Species:

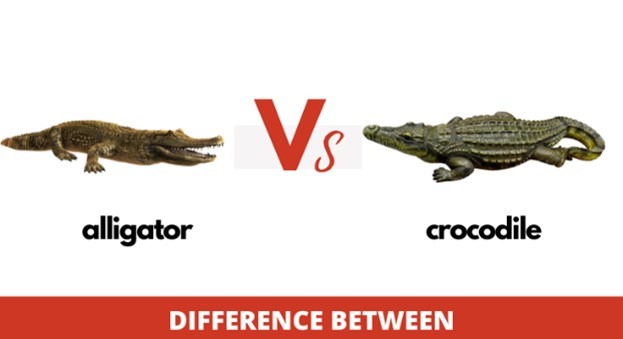

Crocodile vs Alligator vs Gharial:

| Aspect | Crocodiles | Alligators | Gharials |

| Family | Crocodylidae | Alligatoridae | Gavialidae |

| Habitat | Salt water | Fresh water | Fresh Water |

| Distribution | Tropical regions | US, Mexico, and China | Gharial: Found in the Ganges and Indus rivers; False gharial: Native to the Indonesian Islands. |

| Nose Structure | Pointed and V-Shaped | Wide and U-Shaped | Long and thin nose |

| Behaviour | Aggressive | Less Aggressive | Very Shy |

| Size | Large | Small | Medium |

| Bite Force | High | Medium | Low |

| Diet | Opportunistic foragers | Opportunistic foragers | Fish |

| Species | 13 | 8 | 2 |

Indian Crocodile Species:

Gharial (CR):

- Gharials (CR) are freshwater crocodiles that primarily consume fish. They rank among the longest extant crocodilian species.

- Historically, they flourished in the principal rivers of the Indian subcontinent. Currently, they have become extinct in the Indus River, the Brahmaputra in Bhutan and Bangladesh, as well as in the Irrawaddy River.

- Habitat: pristine rivers featuring sandy banks.

- Distribution: The only sustainable population resides within the National Chambal Sanctuary, which spans three states: Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh.

- There are also small non-breeding groups found in the Son, Gandak, Hoogly, and Ghagra rivers, as well as in the Satkosia Wildlife Sanctuary in Odisha.

- Threats: The species faces numerous challenges, including the cumulative impacts of dams, barrages, artificial embankments, alterations in river courses, pollution, sand extraction, riparian agriculture, and the encroachment of domestic and feral livestock.

- IUCN Status: Critically Endangered | CITES: Appendix I | CMS: Appendix I | WPA: Schedule I

Mugger/Indian Crocodile (VU):

- The mugger crocodile, also known as the marsh, Indian, or broad-snouted crocodile, is classified as a freshwater species.

- Habitat: This species inhabits freshwater lakes, rivers, marshes, reservoirs, and shallow, slow-moving water bodies.

- Distribution: It is widely distributed across India but is extinct in Bhutan.

- Threats: The primary threats to this species include habitat loss due to the conversion of natural environments for agricultural and industrial purposes, as well as exploitation in superstitious rituals and for use as aphrodisiacs.

- IUCN Status: VU | CITES Classification: Appendix I | WPA Classification: Schedule I

Saltwater Crocodile (LC):

- The Saltwater Crocodile (LC) holds the title of the largest extant reptile and crocodilian recognized by science.

- Habitat: It thrives in saltwater environments and brackish wetlands.

- Distribution: This species is found along the eastern coast of India (notably in Odisha’s Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary, the coasts of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and the Sundarbans), extending throughout Southeast Asia and the Sundaic region to northern Australia.

- Threats: The species faces threats from poaching for its skin, illegal killings, and the loss of its natural habitat.

- IUCN Status: LC | CITES: Appendix I | WPA: Schedule I

Indian Crocodile Conservation Initiative:

The Indian Crocodile Conservation Initiative has successfully rescued crocodilian species from the threat of extinction and has set them on a promising path toward recovery. Its goals include:

- Safeguarding the remaining crocodilian populations in their natural environments by establishing sanctuaries.

- Accelerating the restoration of natural populations through techniques such as ‘grow and release’ or ‘rear and release.’

- Encouraging captive breeding, where individuals from wild species are captured, bred, and nurtured in specialized facilities under the supervision of wildlife biologists and other specialists. Captivity may serve as a crucial opportunity to ensure the survival of a species in its natural habitat.

Madras Crocodile Bank Trust:

- Located on the outskirts of Chennai, this facility functions as both a reptile zoo and a research center. It houses one of the largest collections of crocodiles and alligators globally.

- The Trust was founded with the aim of conserving Indian crocodilian species, including the marsh or mugger crocodile (VU), the saltwater crocodile (LC), and the gharial (CR). Additionally, it provides a safe nesting area for olive ridley sea turtles (VU).

Conservation of Turtles:

Challenges confronting Indian turtles include poaching for consumption, illicit trade, habitat destruction, and pollution, among others.

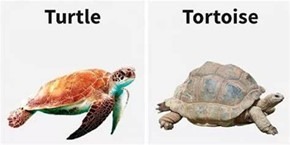

Tortoise vs Turtle

Tortoise:

- Habitat: Primarily terrestrial; engages in all activities on land.

- Swimming Ability: Limited swimming capabilities.

- Diet: Primarily herbivorous, consuming plant matter.

- Lifespan: Notable longevity, typically ranging from 80 to 120 years.

- Size: Generally larger in stature.

- Shell Adaptation: Capable of fully retracting its head into the shell.

Turtle:

- Habitat: Aquatic; ventures onto land solely for the purpose of egg-laying.

- Swimming Ability: Highly proficient swimmers, equipped with paddle-like limbs.

- Diet: Omnivorous, consuming both plant and animal matter.

- Lifespan: Relatively shorter lifespan, averaging between 20 and 40 years.

- Size: Typically smaller in comparison.

- Shell Adaptation: Can only retract its head partially into the shell.

All tortoises fall under the category of turtles, as they are classified within the order Testudines/Chelonia, characterized by their bodies being protected by a bony shell.

- Turtles are omnivorous, consuming both animal and plant matter, with the notable exception of the Green Turtle, which primarily follows a herbivorous diet.

- In terms of size, tortoises are typically larger; however, the Leatherback Sea Turtle, recognized as the largest living turtle species, can weigh up to 500 kilograms. In contrast, the giant tortoises found on the Galápagos Islands are the largest tortoises, reaching weights of up to 415 kilograms.

- Terrapins represent a hybrid between turtles and tortoises, predominantly inhabiting aquatic environments while also being capable of living on land.

Batagur Turtles Species:

Batagur is a genus comprising large river turtles indigenous to South and Southeast Asia. Notable species within this genus include:

- Southern River Terrapin (CR): inhabiting rivers in Southeast Asia.

- Northern River Terrapin (CR): found in the river deltas of Southeast Asia and the Sundarbans.

- Painted Terrapin (CR): residing in the rainforests of Southeast Asia.

- Three-Striped Roofed Turtle (CR): native to the Ganges River.

- Red-Crowned Roofed Turtle (CR): also endemic to the Ganges River.

- Burmese Roofed Turtle (CR): located in the Irrawaddy River of Myanmar.

- The Southern River Terrapin (CR) and Northern River Terrapin (CR) are currently classified under CITES Appendix I, while the other species are categorized in CITES Appendix II.

Northern River Terrapin (Critically Endangered):

- This species ranks among the largest freshwater turtles found in Asia.

- Habitat: river deltas in Southeast Asia and the Sundarbans.

- IUCN Status: Critically Endangered | CITES Classification: Appendix I | WPA Status: Schedule I

Three-Striped Roofed Turtle (Critically Endangered):

- Habitat: Breeds on sandy banks of major rivers.

- Distribution: Found in the Ganges plains across India, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

- IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

- CITES Classification: Appendix II

- Wildlife Protection Act: Schedule I

Red-Crowned (Bengal) Roofed Turtle (CR):

- Males exhibit a smaller size compared to females.

- Habitat: Found in the basins of the Ganga and Brahmaputra Rivers.

- Distribution: Significant populations are primarily located within the National Chambal River Gharial Sanctuary.

- IUCN Status: CR | CITES Classification: Appendix II | WPA Status: Schedule I

Nissilonia Turtle Species:

Nilssonia represents a genus of freshwater softshell turtles inhabiting rivers in South Asia. The principal species within this genus include:

- Burmese Peacock Softshell Turtle (CR): located in Myanmar and the Karbi Anglong district of Assam.

- Leith’s Softshell Turtle (CR): endemic to the rivers of the peninsular region.

- Black Softshell Turtle (CR): indigenous to the lower Brahmaputra River, with only a small population currently surviving in an artificial pond in Chittagong.