In 1600, the East India Company, which was granted an exclusive trading charter by Queen Elizabeth I, brought the British to India as traders. When the Company began to exercise territorial control in 1765, it moved away from its trade position and obtained the “diwani”—the rights to revenue and civil justice—in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. The British Crown assumed direct control of India’s government in 1858 after the Sepoy Mutiny, and this arrangement lasted until August 15, 1947, when India gained independence.

Indian Independence necessitated the drafting of a constitution. In order to address this need, a Constituent Assembly was formed in 1946, and on January 26, 1950, the Constitution was adopted.

Since several significant events during this time created the legal framework for the governance and administration of British India, many elements of the Indian Constitution and political system have their roots in British rule. These noteworthy occurrences are discussed in chronological order under two main headings:

1. The Company Rule (1773-1858)

2. The Crown Rule (1858–1947)

Sub Topics

Regulating Act of 1773

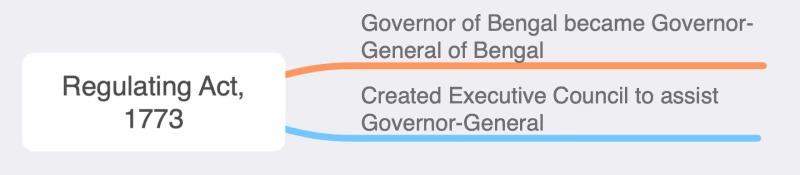

Since it was the first move the British Government took to regulate and supervise the East India Company’s operations in India, the Regulating Act of 1773 was noteworthy for its constitutional implications.

It established the foundation for central administration in India and was the first legislation to recognize the Company’s political and administrative responsibilities.

Key features of the Act included:

1. The designation of the Governor of Bengal as the “Governor-General of Bengal,” along with the creation of a four-member Executive Council to support him. Lord Warren Hastings was the first Governor-General to be appointed under this legislation.

2. Unlike earlier, when the three presidencies were independent of one another, it placed the governors of Bombay and Madras under the governor-general of Bengal.

3. It provided for the creation of a Supreme Court at Calcutta (1774) consisting of a chief justice and three other judges.

4. It barred the Company’s servants from receiving presents or bribes from the “natives” or participating in any kind of private trade.

5. By compelling the Court of Directors, the Company’s governing body, to report on its revenue, civil, and military activities in India, it increased the British Government’s authority over the Company.

Amending Act of 1781

To address the shortcomings of the Regulating Act of 1773, the British Parliament enacted the Amending Act of 1781, also known as the Act of Settlement.

The main features of this Act included:

- For acts taken in their official capacities, it exempted the Council and the Governor-General from the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction. In addition, it exempted Company employees from Supreme Court jurisdiction with regard to their official duties.

- It excluded issues pertaining to revenues collection and revenue-related matters from the Supreme Court’s purview.

- It established that the Supreme Court would have jurisdiction over all inhabitants of Calcutta and mandated that the court administer personal laws to defendants, meaning Hindus would be tried under Hindu law and Muslims under Mohammedan law.

- It specified that appeals from Provincial Courts would be directed to the Governor-General-in-Council rather than the Supreme Court.

- It granted the Governor-General-in-Council the authority to create regulations for the Provincial Courts and Councils.

The 1784 Pitt’s India Act

The Pitt’s India Act2 of 1784 was the following significant law. This Act’s characteristics were as follows:

- It made a distinction between the company’s political and commercial operations.

- It established a new organization called the Board of Control to oversee political activities while allowing the Court of Directors to oversee business affairs. As a result, it created a double government.

- It gave the Board of Control the authority to oversee and manage all aspects of the military and civil administration or income generation of the British colonies in India.

Therefore, the legislation was noteworthy for two reasons: first, the Company’s Indian lands were referred to as “British possessions in India” for the first time; and second, the British Government was granted complete authority over the management of the company’s operations in India.

The 1786 Act

Lord Cornwallis was named Governor-General of Bengal in 1786. In order to accept that position, he made two demands:

. He ought to have the authority to overrule his council’s judgment in certain circumstances.

. In addition, he would serve as Commander-in-Chief.

As a result, both provisions were made by the Act of 1786.

The 1793 Charter Act

This Act’s characteristics were as follows:

1. It increased the supreme authority granted to Lord Cornwallis, to all next governors general and governors of presidency, over his council.

2. It granted the Governor-General additional authority and command over the administrations of the Bombay and Madras sub-presidencies.

3. It gave the company an additional twenty years of trade exclusivity in India.

4. It stated that unless specifically designated, the Commander-in-Chief was not to serve on the Governor-General’s council.

5. It stipulated that the Board of Control members and their employees would now be compensated using Indian income.

The 1813 Charter Act

This Act’s characteristics were as follows:

1. It ended the company’s trade monopoly in India, which means All British merchants were allowed to deal with India. Nonetheless, it maintained the company’s monopoly on tea and trade with China.

2. It affirmed the British Crown’s authority over the Company’s Indian holdings.

3. It made it possible for Christian missionaries to travel to India in order to educate the populace.

4. It made it possible for the people who lived in the British colonies in India to receive an education in the West.

5. It gave Indian local governments the authority to tax citizens. They might also impose penalties on those who fail to pay taxes.

Charter Act of 1833

In British India, this Act was the last step toward centralization.

This Act’s characteristics were as follows:

1.It gave the governor general of Bengal complete civil and military authority and made him the governor general of India. As a result, the legislation established the Government of India for the first time, with jurisdiction over all of the British-owned territory in India. India’s first governor general was Lord William Bentick.

2. It took away the legislative authority of the governors of Madras and Bombay. For all of British India, the Governor-General of India was granted sole legislative authority. The laws created under this act were referred to as Acts, whereas the laws issued under the earlier acts were known as Regulations.

3.It turned the East India Company into a purely administrative organization and put an end to its commercial operations. According to this clause, the Company owned its holdings in India “in trust for His Majesty, His heirs and successors.”

4. The Charter Act of 1833 declared that Indians should not be prohibited from holding any position, office, or job within the Company and aimed to establish an open competitive system for the selection of civil servants. But once the Court of Directors objected, this clause was removed.

Charter Act of 1853

The British Parliament passed a number of Charter Acts between 1793 and 1853, this being the final one. It was an important turning point in the constitution.

This Act’s characteristics were as follows:

1. It separated the Governor-General’s Council’s executive and legislative branches for the first time. It allowed for the council to have six more members, known as legislative councillors. Stated differently, it created a distinct legislative body for the Governor-General, which became known as the Indian (Central) Legislative body. Using the same processes as the British Parliament, this council’s legislative branch operated as a miniature parliament. As a result, legislation was for the first time regarded as a unique government role that called for unique tools and procedures.

2. It instituted a system of open competition for civil servant recruitment and selection. Thus, the Indians were likewise granted access to the covenanted civil service3. Consequently, in 1854, the Committee on the Indian Civil Service, sometimes known as the Macaulay Committee, was established.

3. It gave the Company more authority and permitted it to hold onto Indian lands held in trust for the British Crown.

However, in contrast to the earlier Charters, it did not set a certain time frame. This was a blatant sign that the Parliament could end the Company’s reign whenever it pleased.

4. It brought local representation to the Indian (Central) Legislative Council for the first time. Four out of the Governor General’s Council’s six new lawmakers were appointed by the local (provincial)governments of Madras, Bombay, Bengal and Agra.

Sub Topics

The Crown Rule (1858-1947)

Government of India Act 1858

Following the Revolt of 1857, commonly referred to as the First War of Independence or the “sepoy mutiny,” this important Act was passed. The legislation referred to as the Good Government Act of

India, disbanded the East India Company, and gave the British Crown control over the country’s lands, government, and income.

This Act’s characteristics were as follows:

- It stated that Her Majesty was to rule India going forward and in her name. The title of Governor-General of India was replaced with Viceroy of India. In India, he (the viceroy) served as the British Crown’s immediate envoy. Thus, Lord Canning was appointed India’s first viceroy.

- The Act abolished the system of double government by eliminating the Board of Control and the Court of Directors.

- It introduced a new position, the Secretary of State for India, who was given full authority and control over Indian administration. This Secretary was a member of the British Cabinet and was ultimately accountable to the British Parliament.

- A 15-member Council of India was established to assist the Secretary of State for India. This council served as an advisory body, with the Secretary of State acting as its chairman.

- The Act also established the Secretary of State-in-Council as a corporate entity, allowing it to sue and be sued in both India and England.

The Act of 1858 primarily focused on enhancing the administrative structure that oversaw the Indian Government from England. It did not bring about significant changes to the existing system of government in India.

Indian Councils Act of 1861

Following the significant revolt of 1857, the British Government recognized the need to enlist the cooperation of Indians in the administration of their country. To move towards this goal of inclusion, three acts were enacted by the British Parliament in 1861, 1892, and 1909. The Indian Councils Act of 1861 serves as a crucial milestone in the constitutional and political history of India.

Key features of the Indian Councils Act of 1861 include:

- Introduction of Representative Institutions: The Act marked the beginning of representative institutions by involving Indians in the law-making process. It stipulated that the Viceroy should appoint some Indians as non-official members of his expanded council. In 1862, Lord Canning, the then Viceroy, nominated three Indians to his legislative council: the Raja of Benaras, the Maharaja of Patiala, and Sir Dinkar Rao.

- Decentralization of Power: The Act initiated the process of decentralization by restoring legislative powers to the Bombay and Madras Presidencies. This change reversed the centralizing trend that began with the Regulating Act of 1773 and peaked under the Charter Act of 1833. This policy of legislative devolution ultimately led to granting almost complete internal autonomy to the provinces in 1937.

- Establishment of New Legislative Councils: The Act provided for the creation of new legislative councils for Bengal, the North-Western Provinces, and Punjab, which were established in 1862, 1886, and 1897, respectively.

- Empowerment of the Viceroy: It empowered the Viceroy to create rules and orders for the efficient functioning of the council. Additionally, it recognized the ‘portfolio’ system introduced by Lord Canning in 1859, whereby members of the Viceroy’s council were assigned responsibility for one or more government departments and authorized to issue final decisions on behalf of the council regarding matters in their department(s).

- Ordinance Authority: The Act allowed the Viceroy to issue ordinances without the approval of the legislative council during emergencies, with each ordinance having a lifespan of six months.

These features reflect the significant steps taken towards inclusivity and governance reform in colonial India.

Indian Councils Act of 1892

The Indian Councils Act of 1892 introduced several important features aimed at enhancing the legislative framework in India. The key provisions of this Act are as follows:

- Increase in Non-official Members: The Act expanded the number of additional (non-official) members in both the Central and provincial legislative councils, while still ensuring that the official majority was maintained.

- Enhanced Legislative Functions: It broadened the functions of the legislative councils, empowering them to discuss the budget and to address questions to the executive.

- Nomination of Non-official Members: The Act outlined the process for nominating non-official members to the legislative councils. Specifically:

– The Viceroy could nominate some non-official members to the Central Legislative Council based on recommendations from the provincial legislative councils and the Bengal Chamber of Commerce.

– Governors could nominate members to the provincial legislative councils based on recommendations from various local bodies, including district boards, municipalities, universities, trade associations, zamindars, and chambers of commerce.

While the Act included a limited provision for using elections to fill some non-official seats in both the Central and provincial legislative councils, it did not explicitly use the term “election.” Instead, the process was characterized as nominations made on the recommendation of specific bodies.

These provisions represented a gradual move towards greater Indian participation in governance while still maintaining British control over the legislative process.

Indian Councils Act of 1909

The Indian Councils Act of 1909, commonly referred to as the Morley-Minto Reforms (named after then Secretary of State for India, Lord Morley, and then Viceroy of India, Lord Minto), introduced several crucial features:

- Expansion of Legislative Councils: The Act significantly increased the membership of both the Central and provincial legislative councils. The number of members in the Central legislative council was raised from 16 to 60, while the number of members in provincial councils varied.

- Official Majority Retained: While the Act maintained an official majority in the Central legislative council, it allowed the provincial legislative councils to have a non-official majority.

- Enhanced Deliberative Functions: The Act enlarged the deliberative roles of the legislative councils at both levels. Members were permitted to ask supplementary questions, move resolutions regarding the budget, and engage in more detailed discussions.

- Inclusion of Indians in Executive Councils: For the first time, the Act provided for the inclusion of Indians in the executive councils of the Viceroy and Governors. Satyendra Prasad Sinha became the first Indian member of the Viceroy’s executive council, serving as the Law Member.

- Communal Representation for Muslims: The Act established a system of communal representation by introducing the concept of a “separate electorate” for Muslims. Under this system, Muslim representatives were to be elected solely by Muslim voters, which effectively legitimized communalism in the electoral process. As a result, Lord Minto became known as the Father of the Communal Electorate.

- Separate Representation for Other Groups: The Act also provided for separate representation for presidency corporations, chambers of commerce, universities, and zamindars.

Government of India Act of 1919

On August 20, 1917, the British Government announced its aim to gradually introduce responsible government in India. This led to the enactment of the Government of India Act of 1919, which came into effect in 1921 and is also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms (named after Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, and Lord Chelmsford, the Viceroy of India).

Key features of this Act include:

- Decentralization of Power:

The Act reduced central control over the provinces by delineating and separating central and provincial subjects. Both central and provincial legislatures were authorized to legislate on their respective lists of subjects. However, the overall structure of government remained centralized and unitary in nature.

These Acts represented significant steps in the evolution of constitutional development and governance in India, marking a shift toward greater Indian participation in the political process.

- Division of Provincial Subjects:

The Act further categorized provincial subjects into two types—transferred and reserved. Transferred subjects were to be managed by the Governor with the assistance of Ministers who were accountable to the legislative council. In contrast, reserved subjects were to be administered solely by the Governor and his executive council, without any accountability to the legislative council. This dual governance structure was termed ‘dyarchy,’ originating from the Greek word “dyarchy,” meaning double rule. However, this system proved largely ineffective.

- Introduction of Bicameralism and Direct Elections:

For the first time, the Act introduced bicameralism and direct elections in India. The Indian legislative council was replaced by a bicameral legislature, comprising an Upper House (Council of State) and a Lower House (Legislative Assembly). Most members of both Houses were elected directly by the electorate.

- Inclusion of Indian Members in the Executive Council:

The Act stipulated that three of the six members of the Viceroy’s executive council (excluding the Commander-in-Chief) would be Indians.

- Extension of Communal Representation:

The principle of communal representation was expanded under the Act, providing for separate electorates for Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and Europeans.

- Limited Franchise:

The Act granted voting rights to a limited segment of the population based on criteria such as property ownership, tax payments, or educational qualifications.

- Establishment of the High Commissioner for India:

A new office, the High Commissioner for India, was created in London, taking over some functions previously performed by the Secretary of State for India.

- Public Service Commission:

The Act mandated the establishment of a public service commission, leading to the creation of the Central Public Service Commission in 1926 for the recruitment of civil servants.

- Separation of Provincial Budgets:

For the first time, provincial budgets were separated from the central budget, allowing provincial legislatures to enact their own budgets.

- Statutory Commission:

The Act provided for the establishment of a statutory commission to review its functioning and report on the effectiveness of the Act after ten years of its implementation.

These features marked significant changes in the governance structure in India, laying the groundwork for increased Indian participation in the political process and introducing reforms aimed at creating a more representative system.Top of Form

Simon Commission

In November 1927, two years ahead of the scheduled date, the British Government announced the establishment of a seven-member statutory commission chaired by Sir John Simon. The purpose of the commission was to assess the situation in India under its new Constitution. Notably, all members of the commission were British, which led to a boycott from all Indian political parties. The commission submitted its report in 1930, which recommended several changes, including:

– The abolition of dyarchy.

– The extension of responsible government in the provinces.

– The establishment of a federation encompassing both British India and the princely states.

– The continuation of communal electorates.

To discuss and evaluate the commission’s proposals, the British Government organized three round table conferences, bringing together representatives from the British Government, British India, and Indian princely states. Following these discussions, a “White Paper on Constitutional Reforms” was prepared and submitted to the Joint Select Committee of the British Parliament. The recommendations put forth by this committee were subsequently incorporated, with some amendments, into the Government of India Act of 1935.

Communal Award

In August 1932, Ramsay MacDonald, the British Prime Minister, introduced a plan for the representation of minorities known as the Communal Award. This award not only maintained separate electorates for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and Europeans but also extended this provision to the depressed classes (Scheduled Castes). Mahatma Gandhi was deeply disheartened by this expansion of communal representation to the depressed classes and undertook a fast unto death in Yerawada Jail (Pune) to advocate for a modification of the award.

Ultimately, an agreement was reached between the leaders of the Congress and the representatives of the depressed classes, known as the Poona Pact. This agreement preserved the Hindu joint electorate and allocated reserved seats for the depressed classes.

Government of India Act of 1935

The Government of India Act of 1935 is regarded as a significant milestone towards establishing a more responsible government in India. It was an extensive and detailed document comprising 321 sections and 10 schedules, outlining various aspects of governance and institutional structure in India.

The Government of India Act of 1935 included several significant features:

- Establishment of an All-India Federation:

The Act proposed an All-India Federation comprising provinces and princely states as units. Powers were divided between the Centre and the units through three lists: the Federal List (containing 59 items for the Centre), the Provincial List (54 items for the provinces), and the Concurrent List (36 items for both). Residuary powers were assigned to the Viceroy. However, the federation was never realized as the princely states chose not to participate.

- Abolishment of Dyarchy in Provinces:

The Act abolished dyarchy and introduced ‘provincial autonomy.’ Provinces were empowered to act as autonomous administrative units within defined areas. Additionally, responsible government was instituted in provinces, which required the Governor to act upon the advice of ministers accountable to the provincial legislature. This arrangement was operational from 1937 until its discontinuation in 1939.

- Adoption of Dyarchy at the Centre:

The Act proposed the reintroduction of dyarchy at the Centre, dividing federal subjects into reserved subjects and transferred subjects. However, this provision did not come into effect.

- Introduction of Bicameralism:

Bicameral legislatures were established in six of the eleven provinces, specifically Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Bihar, Assam, and the United Provinces. These legislatures comprised a legislative council (upper house) and a legislative assembly (lower house), though significant restrictions were placed on their functions.

- Extended Communal Representation:

The Act expanded the principle of communal representation by providing separate electorates for the depressed classes (Scheduled Castes), women, and labourers.

- Abolishment of the Council of India:

The Council of India, established by the Government of India Act of 1858, was abolished, and the Secretary of State for India was supported by a team of advisors.

- Extension of Franchise:

The Act broadened the voting rights, extending them to roughly 10 percent of the total population.

- Establishment of the Reserve Bank of India:

The Act provided for the creation of the Reserve Bank of India to manage the currency and credit of the nation.

- Public Service Commissions:

It established a Federal Public Service Commission, as well as Provincial Public Service Commissions and a Joint Public Service Commission for two or more provinces.

- Establishment of a Federal Court:

The Act provided for the creation of a Federal Court, which was established in 1937.

Indian Independence Act of 1947

On February 20, 1947, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee announced that British rule in India would cease by June 30, 1948, after which power would be transferred to responsible Indian leaders. This announcement was met with heightened agitation from the Muslim League, which demanded the partition of the country. On June 3, 1947, the British Government clarified that any Constitution drafted by the Constituent Assembly (formed in 1946) would not be applicable in areas unwilling to accept it. On the same day, Lord Mountbatten, the Viceroy of India, proposed the partition plan, known as the Mountbatten Plan, which was accepted by both the Congress and the Muslim League. The plan was promptly enacted through the Indian Independence Act of 1947.

Key features of this Act included:

- Termination of British Rule:

The Act officially ended British rule in India, declaring India an independent and sovereign state as of August 15, 1947.

- Partition of India:

It provided for the partition of India and the creation of two independent dominions—India and Pakistan—with the right to secede from the British Commonwealth.

- Abolishment of the Office of Viceroy:

The position of Viceroy was abolished and replaced by a Governor-General for each dominion, who would be appointed by the British King upon the advice of the dominion cabinet. The British Government would have no responsibility regarding the governance of India or Pakistan.

- Constitution-Making Authority:

The Act empowered the Constituent Assemblies of both dominions to draft and adopt their respective constitutions and to repeal any acts of the British Parliament, including the Independence Act itself.

These provisions marked a pivotal moment in Indian history, culminating in the establishment of independent governance in India and Pakistan.

- Legislative Powers of Constituent Assemblies:

The Act empowered the Constituent Assemblies of both dominions to legislate for their respective territories until new constitutions were developed and implemented. No Act of the British Parliament passed after August 15, 1947, would apply to either of the new dominions unless specifically extended by law from the legislature of that dominion.

- Abolishment of the Secretary of State for India:

The Act abolished the office of the Secretary of State for India, transferring his responsibilities to the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs.

- Lapse of British Paramountcy:

The Act declared the lapse of British paramountcy over the Indian princely states and ended treaty relations with tribal areas effective from August 15, 1947.

- Freedom for Princely States:

The Act granted Indian princely states the freedom to either join the Dominion of India or the Dominion of Pakistan, or choose to remain independent.

- Continuation of Governance:

It provided for the continuation of governance in each of the dominions and provinces under the Government of India Act of 1935 until new constitutions were framed. The dominions were permitted to make modifications to the Act as necessary.

- Veto Power:

The Act removed the British Monarch’s right to veto bills or request the reservation of certain bills for royal approval. This power was retained for the Governor-General, who was authorized to assent to any bill in the name of His Majesty.

- Governor-General and Nominal Heads:

The Act designated the Governor-General of India and provincial governors as constitutional (nominal) heads of their respective states, requiring them to act based on the advice of the respective councils of ministers in all matters.

- Removal of the Title “Emperor of India”:

The Act eliminated the title “Emperor of India” from the royal titles held by the King of England.

- Civil Service Appointments:

The appointment of civil servants and the reservation of posts by the Secretary of State for India were discontinued. However, members of the civil services who were appointed before August 15, 1947, continued to enjoy all benefits entitled to them up to that time.

At the stroke of midnight on August 14-15, 1947, British rule officially ended, and power was transferred to the two newly independent Dominions of India and Pakistan. Lord Mountbatten became the first Governor-General of the Dominion of India, swearing in Jawaharlal Nehru as its first Prime Minister. The Constituent Assembly of India, formed in 1946, subsequently became the Parliament of the Indian Dominion.

Interim Government (1946)

The Interim Government of India was formed in 1946 with various key members taking on specific portfolios. Below is a list of the members and the portfolios they held:

Sl. No. | Members | Portfolios Held |

1 | Jawaharlal Nehru | Vice-President of the Council; External Affairs & Commonwealth Relations |

2 | Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel | Home, Information & Broadcasting |

3 | Dr. Rajendra Prasad | Food & Agriculture |

4 | Dr. John Mathai | Industries & Supplies |

5 | Jagjivan Ram | Labour |

6 | Sardar Baldev Singh | Defence |

7 | C.H. Bhabha | Works, Mines & Power |

8 | Liaquat Ali Khan | Finance |

9 | Abdur Rab Nishtar | Posts & Air |

10 | Asaf Ali | Railways & Transport |

11 | C. Rajagopalachari | Education & Arts |

12 | I.I. Chundrigar | Commerce |

13 | Ghaznafar Ali Khan | Health |

14 | Joginder Nath Mandal | Law |

Note: The members of the Interim Government also served on the Viceroy’s Executive Council. The Viceroy remained the head of this council, while Jawaharlal Nehru held the position of Vice-President of the Council.

First Cabinet of Free India (1947)

The first Cabinet of Free India was formed in 1947 following India’s independence. Below is a list of the cabinet members along with their respective portfolios:

Sl. No. | Members | Portfolios Held |

1 | Jawaharlal Nehru | Prime Minister; External Affairs & Commonwealth Relations; Scientific Research |

2 | Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel | Home, Information & Broadcasting; States |

3 | Dr. Rajendra Prasad | Food & Agriculture |

4 | Maulana Abul Kalam Azad | Education |

5 | Dr. John Mathai | Railways & Transport |

6 | R.K. Shanmugham Chetty | Finance |

7 | Dr. B.R. Ambedkar | Law |

8 | Jagjivan Ram | Labour |

9 | Sardar Baldev Singh | Defence |

10 | Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur | Health |

11 | C.H. Bhabha | Commerce |

12 | Rafi Ahmed Kidwai | Communication |

13 | Dr. Shayama Prasad Mukherji | Industries & Supplies |

14 | V.N. Gadgil | Works, Mines & Power |

This cabinet played a crucial role in shaping the policies and direction of India as it embarked on its journey of independence and self-governance.Bottom of Form

Introduction

The Industrial Revolution, which began in the late 18th century, was a transformative period that reshaped production methods through technological advancements and mass manufacturing. This revolution not only revolutionized production but also had a profound impact on global politics, driving European powers to expand their colonial empires. The need for raw materials, new markets, and labor to sustain industrial growth led to the intensification of European colonialism.

Body

1. The Industrial Revolution and the Transformation of Production

- Technological Advancements:

The invention of the steam engine by James Watt and innovations in textile production significantly boosted manufacturing capacities. Factories began mass-producing goods at faster rates, and technological improvements like machine tools and mass production techniques lowered production costs, making goods more affordable and accessible.

Innovations in transportation, such as steamships and railways, further enhanced the efficiency of moving raw materials, accelerating industrial production. - Shift in Economic Structures:

The rise of factories and the decline of traditional cottage industries marked a shift from agrarian economies to urban, industrial economies. This transformation fostered the growth of urban centers and the rise of a new industrial working class. Industries like textiles, iron, and steel grew rapidly, requiring large-scale production systems to meet the demands of global markets. - Increased Productivity:

Advances such as the spinning jenny and power loom revolutionized textile production, allowing Britain to dominate the global textile trade. Mass production techniques, such as interchangeable parts, facilitated the assembly of complex goods like machinery, tools, and transport vehicles, further propelling industrial growth.

2. The Industrial Revolution and the Expansion of European Colonialism

- Demand for Raw Materials:

The Industrial Revolution created an insatiable demand for raw materials, such as cotton, rubber, oil, and minerals. European powers turned to their colonies—India, Africa, and Southeast Asia—to supply these resources. For instance, India became a key supplier of cotton for Britain’s textile mills, while rubber from Africa contributed to the growing automobile and industrial sectors in Europe. - New Markets for Manufactured Goods:

European powers sought new markets for their mass-produced goods, and their colonies became captive markets for these products. This trade dynamic ensured that the wealth generated from industrial production flowed back to the imperial powers. Local industries in colonies were often undermined by the influx of European manufactured goods, such as textiles, while colonies were coerced into purchasing European products due to imperial trade policies, such as the British East India Company’s monopoly in India. - Technological Advancements and Imperial Control:

Steamships, railroads, and telegraph lines played a crucial role in expanding European territorial control over distant colonies. These innovations facilitated the movement of troops, supplies, and resources, enabling more effective governance and exploitation. Additionally, military technologies like the Maxim gun gave European powers a decisive advantage in suppressing local resistance, securing imperial dominance. - Exploitation of Labor:

The demand for cheap labor driven by industrial growth led European powers to exploit colonial populations. In India, indentured servitude became widespread, with workers subjected to long-term, exploitative labor contracts in plantations and construction projects, such as the railway system. This form of labor exploitation contributed to the wealth of the imperial powers while reinforcing the colonial economic structure.

Conclusion

The Industrial Revolution revolutionized global production methods and spurred the expansion of European colonialism, as industrial powers sought to secure raw materials, markets, and labor. This interconnectedness between industrial growth and imperialism not only reshaped the global economy but also laid the foundation for enduring global inequalities that continue to affect the modern world.

Introduction

The Indian nationalist movement, spanning the 19th and 20th centuries, was not merely a political effort against British colonial rule but also a profound cultural renaissance. This cultural revival aimed at reclaiming and redefining India’s identity and heritage, thereby strengthening the foundations of political resistance. The relationship between cultural regeneration and political resistance was mutually reinforcing, with each driving the other forward.

Body

1. Cultural Regeneration as the Foundation of Political Resistance

Rediscovery of India’s Cultural Heritage:

Indian reformers and scholars played a significant role in reviving and promoting the country’s ancient cultural and philosophical traditions. Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Swami Vivekananda sought to reintroduce the teachings of ancient texts, fostering a sense of national pride.

Example: Dayananda Saraswati and the Arya Samaj advocated for a return to Vedic values, framing it as a rejection of the colonial imposition on Indian culture.The Bengal Renaissance and Nationalism:

The Bengal Renaissance, spearheaded by thinkers like Rabindranath Tagore and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, integrated cultural revival with nationalist ideas. Their works encouraged a resurgence of Indian consciousness.

Example: Bankim Chandra’s Anandamath, which introduced “Vande Mataram” as a national symbol, became a rallying cry for the nationalist movement.Education as a Catalyst for Cultural Renewal:

Institutions like Banaras Hindu University (BHU), founded by Madan Mohan Malaviya, combined modern education with Indian traditional values, strengthening the intellectual foundation for political resistance.

Leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak used educational initiatives to cultivate a sense of national identity and to promote resistance against British colonial rule.Integration of Folk Culture into the Nationalist Struggle:

Folk songs, stories, and symbols, which were vital parts of India’s rural traditions, became instrumental in mobilizing the masses for the nationalist cause.

Example: The bhajan Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram, popularized by Mahatma Gandhi, became a unifying anthem that resonated with people across regions and communities.

2. Political Resistance Fueling Cultural Revival

Religious Symbolism in Political Mobilization:

Political leaders effectively utilized cultural and religious symbolism to stir nationalist sentiment and unite people across India.

Example: Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s promotion of Ganesh Chaturthi as a public festival served not only to celebrate Indian culture but also to foster a sense of unity and pride among the masses.Countering British Cultural Hegemony:

The nationalist movement sought to challenge the British narrative that portrayed Indians as “uncivilized” and inferior. Cultural narratives highlighting India’s rich heritage became essential in building pride in India’s past.

Example: Swami Vivekananda’s speech at the 1893 Chicago Parliament of Religions emphasized India’s spiritual depth, positioning Indian culture as intellectually and morally superior, thus empowering political resistance.

Conclusion

The Indian nationalist movement was a powerful fusion of cultural regeneration and political resistance. Cultural revival instilled a sense of pride and unity, which invigorated the political struggle against British rule. Conversely, the political resistance provided the necessary urgency and platform for cultural renewal, ensuring its broad reach. This synergy between culture and politics laid the foundation for India’s eventual independence.

Historical Background

1. Regulating Act , 1973