Subordinate Courts

Subordinate Courts in India

The state judiciary comprises a high court and a network of subordinate courts, commonly referred to as lower courts, which operate under the high court’s jurisdiction at the district and lower levels.

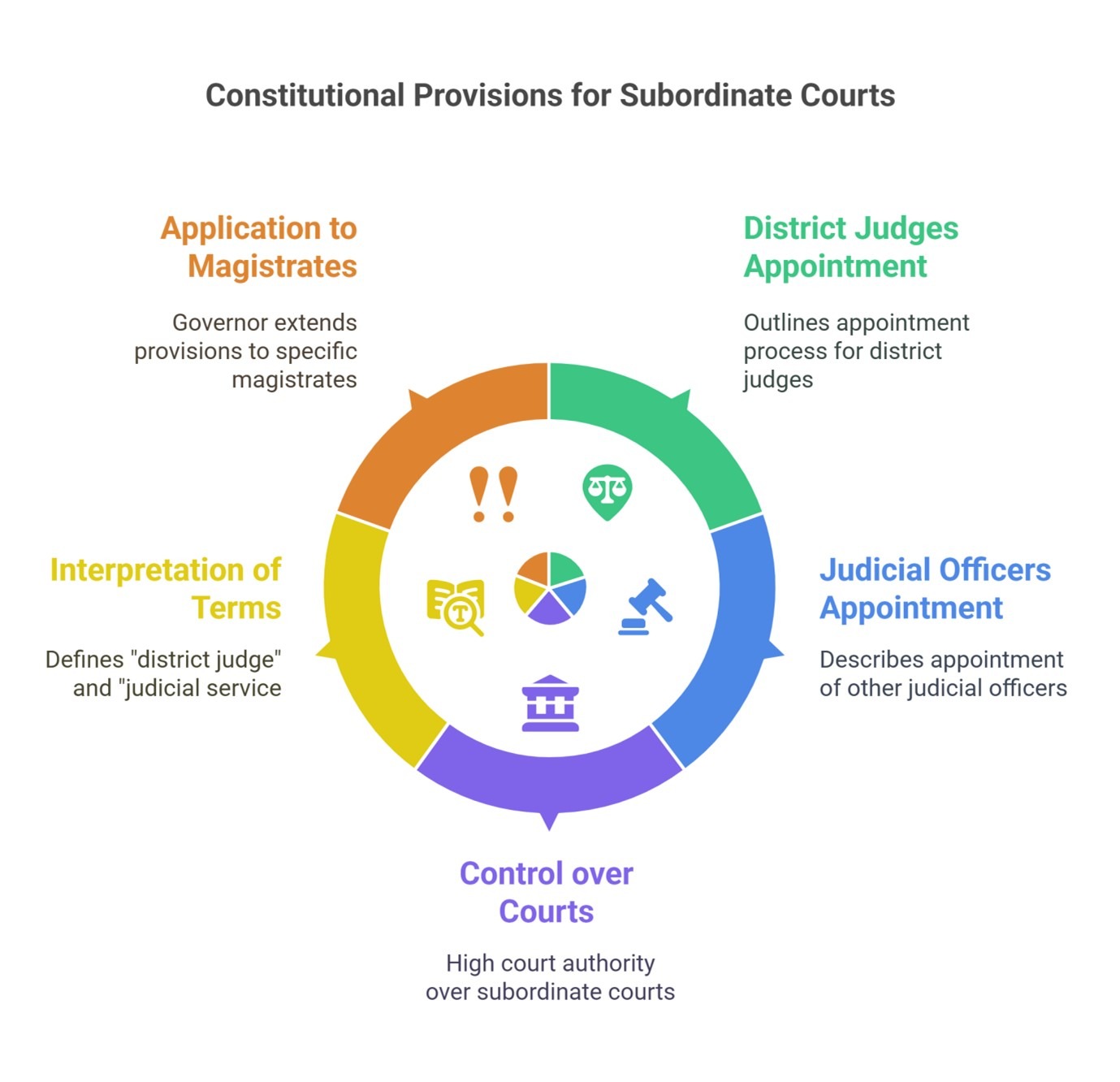

Constitutional Provisions for Subordinate Courts

Articles 233 to 237 of the Indian Constitution outline the framework for the organization and independence of subordinate courts. Key provisions include:

1. Appointment of District Judges:

- The governor of the state, in consultation with the high court, is responsible for the appointment, posting, and promotion of district judges.

- Qualifications for district judges include:

- The individual must not be already in service with the Central or state government.

- The candidate should have served as an advocate or pleader for a minimum of seven years.

- They must be recommended by the high court for appointment.

2. Appointment of Other Judicial Officers:

- For appointing persons (other than district judges) to the judicial service, the governor consults both the State Public Service Commission and the high court.

3. Control over Subordinate Courts:

- The high court has the authority to control district courts and other subordinate courts concerning the posting, promotion, and leave of judicial officers below the rank of district judge.

4. Interpretation of Key Terms:

- The term “district judge” encompasses a variety of positions, including:

- Judges of city civil courts

- Additional district judges

- Joint district judges

- Assistant district judges

- Chief judges of small cause courts

- Chief presidency magistrates

- Additional chief presidency magistrates

- Sessions judges

- Additional sessions judges and assistant sessions judges.

- The term “district judge” encompasses a variety of positions, including:

-

- “Judicial service” refers exclusively to personnel aiming to fill district judge positions and other civil judicial roles subordinate to them.

5. Application of Provisions to Magistrates:

- The governor may extend the above provisions concerning the state judicial service to specific classes of magistrates as necessary.

The framework established by Articles 233 to 237 is crucial for maintaining the structure and functioning of subordinate courts in India. These provisions ensure that appointments are made based on merit, promote judicial independence, and provide the necessary mechanism for governance and control over the judicial system at state levels.

STRUCTURE AND JURISDICTION

District Courts and Hierarchy of Subordinate Courts

In the Indian judicial system, the district judge serves as the highest judicial authority within a district, possessing both original and appellate jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters. His roles and the structure of subordinate courts are essential for ensuring justice at the local level.

Role of the District Judge

- The district judge also functions as the sessions judge, distinguishing his title based on the type of case he is handling:

- Civil Cases: Known as the District Judge

- Criminal Cases: Known as the Sessions Judge

- The district judge holds both judicial and administrative powers and supervises all subordinate courts in the district.

- Appeals from decisions made by the district judge are directed to the High Court.

- In his capacity as a sessions judge, he has the authority to impose sentences, including life imprisonment and capital punishment. However, any capital punishment must be confirmed by the High Court, irrespective of whether an appeal is filed.

- The district judge also functions as the sessions judge, distinguishing his title based on the type of case he is handling:

Hierarchical Structure of Subordinate Courts

1. Court of Subordinate Judge (Civil Side):

- Exercises unlimited pecuniary jurisdiction over civil suits and handles cases where the monetary stakes are significant.

2. Court of Chief Judicial Magistrate (Criminal Side):

- Deals with criminal cases where the punishment can extend to imprisonment for up to seven years.

3. Court of Munsiff (Civil Side):

- Functions at the lowest level in civil matters, addressing cases with limited jurisdiction over smaller monetary stakes.

4. Court of Judicial Magistrate (Criminal Side):

- Handles criminal matters punishable by imprisonment of up to three years.

5. City Civil Courts and Metropolitan Magistrates:

- Found in metropolitan areas, with chief judges overseeing civil cases and magistrates handling criminal cases.

6. Small Causes Courts:

- Established in certain states and presidency towns to resolve civil cases of small value quickly and summarily. Their decisions are final, although the High Court retains revisionary powers.

7. Panchayat Courts:

- In some states, these courts address petty civil and criminal cases and may be referred to by names like Nyaya Panchayat, Gram Kutchery, Adalati Panchayat, or Panchayat Adalat.

Constitutional Provisions Related to Subordinate Courts

The following articles of the Constitution outline the provisions relevant to subordinate courts:

Article No. | Subject Matter |

233 | Appointment of district judges |

233A | Validation of appointments of, and judgments delivered by certain district judges |

234 | Recruitment of persons other than district judges to the judicial service |

235 | Control over subordinate courts |

236 | Interpretation |

237 | Application of the provisions of this chapter to certain classes of Magistrates |

The structure of subordinate courts in India, including the roles of the district judge, support the efficient delivery of justice at all levels. Articles 233 to 237 establish a constitutional framework governing the judiciary, ensuring appointments, recruitment, and control to maintain the integrity and independence of the judicial system.

National Legal Services Authority (NALSA)

Constitutional Basis

- Article 39A of the Constitution of India mandates free legal aid for the poor and weaker sections of society, ensuring justice for all.

- Articles 14 (equality before law) and 22(1) (protection against arrest and detention) reinforce the obligation of the State to promote justice and equality of opportunity.

Establishment of NALSA

- The Legal Services Authorities Act was enacted by Parliament in 1987 and came into force on November 9, 1995, to create a standardized framework across the country for providing free and competent legal services to disadvantaged communities.

- NALSA was constituted under this Act to oversee the implementation of legal aid programs, establish policies, and frame principles for delivering legal services.

Structure of Legal Services Authorities

- State Legal Services Authority (SLSA): Established in every state.

- High Court Legal Services Committee: Formed in each High Court.

- District Legal Services Authorities (DLSA) and Taluk Legal Services Committees: Set up at the district and taluk levels to implement NALSA’s policies and conduct Lok Adalats.

Functions of NALSA and Legal Services Authorities

The primary functions of the state and district legal services authorities include:

- Providing Free Legal Services: Ensuring eligible individuals receive competent legal aid.

- Organizing Lok Adalats: Facilitating amicable dispute resolution through Lok Adalats.

- Conducting Legal Awareness Camps: Raising legal awareness, particularly in rural areas.

What Free Legal Services Include

NALSA provides a range of free legal services, which encompass:

- Waiver of court fees, process fees, and other associated costs related to legal proceedings.

- Provision of legal representation through appointed lawyers.

- Assistance in obtaining certified copies of orders and documents relevant to legal proceedings.

- Support in preparing appeals, including necessary documentation like printing and translation.

Eligibility for Free Legal Services

Eligible individuals for availing free legal services include:

- Women and Children

- Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes (SC/ST)

- Industrial Workmen

- Victims of Mass Disasters: Such as those affected by violence, floods, droughts, earthquakes, and industrial disasters.

- Disabled Persons

- Persons in Custody

- Individuals with Annual Income Below ₹1 Lakh (or ₹1,25,000 for services related to the Supreme Court)

- Victims of Human Trafficking or Begar

The National Legal Services Authority plays a pivotal role in promoting access to justice for marginalized and economically disadvantaged populations in India. Through its structured approach and designated authorities at various levels, NALSA aims to ensure that legal services are not just a privilege for the affluent but a right for every citizen, thus furthering the cause of social justice.

Lok Adalats

Lok Adalat translates to “People’s Court,” and serves as a forum for amicably settling disputes either pending in courts or at the pre-litigation stage. This initiative is part of the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) system, aimed at providing accessible, inexpensive, and efficient justice, thereby alleviating the burden on the regular court system.

Meaning and Principles

The Supreme Court emphasizes that Lok Adalats are rooted in traditional Indian dispute resolution practices, drawing inspiration from Gandhian principles. They operate on the notion that there are no winners or losers; instead, disputes are resolved collaboratively, fostering goodwill among parties involved.

Statutory Status

- The first Lok Adalat after independence was organized in Gujarat in 1982, which laid the groundwork for its expansion across India.

- The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, conferred statutory recognition on Lok Adalats, formalizing their operations within the legal framework.

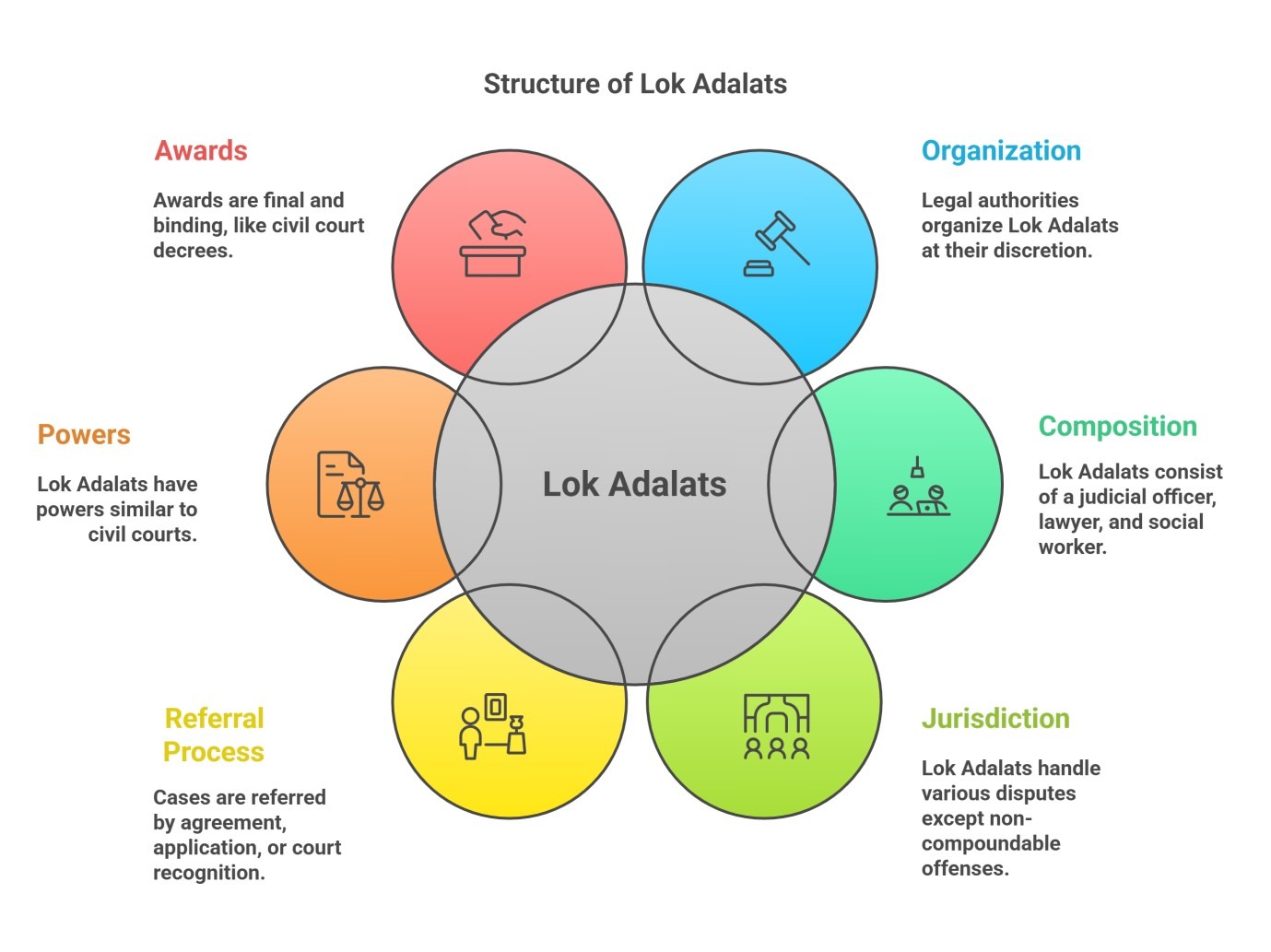

Key Provisions Relating to Lok Adalats

1. Organization:

- Lok Adalats can be organized by various legal service authorities, including State Legal Services Authorities, District Legal Services Authorities, and others, at their discretion regarding timing and jurisdiction.

2. Composition: Typically, a Lok Adalat consists of:

- A judicial officer as the chairman.

- A lawyer (advocate) and a social worker as members.

3. Jurisdiction:

- Lok Adalats can resolve:

- Cases pending before any court.

- Disputes that have not yet been brought to court.

- They handle a range of matters, including family disputes, criminal cases (compoundable offenses), land acquisition, labor disputes, consumer grievances, and more. However, cases involving non-compoundable offenses are outside their jurisdiction.

- Lok Adalats can resolve:

4. Referral Process:

- A case can be referred to a Lok Adalat if:

- All parties agree to settle.

- A party applies to the court for referral.

- The court recognizes the case as appropriate for Lok Adalat.

- For pre-litigation disputes, any party can initiate referral by applying to the organizing authority.

- A case can be referred to a Lok Adalat if:

5. Powers:

- Lok Adalats possess powers similar to civil courts, including:

- Summoning witnesses and enforcing their attendance.

- Obtaining documents.

- Receiving evidence via affidavits.

- They can specify their own procedures while proceedings are deemed judicial.

- Lok Adalats possess powers similar to civil courts, including:

6. Awards:

- Awards made by Lok Adalats are considered decrees of civil courts and are final and binding on all parties. No appeals can be made against these awards.

Benefits of Lok Adalats

The advantages of utilizing Lok Adalats include:

- No Court Fees: There are no fees, and previously paid fees can be refunded if disputes are resolved.

- Procedural Flexibility: Less stringent procedural requirements enhance the speed of resolution.

- Direct Interaction: Parties can engage directly with the adjudicating members through their counsel.

- Binding Nature: The decisions are binding and non-appealable, allowing for quick resolution.

Advantages of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

The Law Commission of India outlines the benefits of ADR, including Lok Adalats:

- Cost-Effective: Lower costs compared to litigation.

- Time-Efficient: Quicker resolution than traditional court processes.

- Reduced Technicality: Less an emphasis on legal formalities.

- Confidentiality: Parties can discuss issues without fear of public disclosures.

- Collaborative Approach: Promotes a sense of no definitive losing or winning side while addressing grievances effectively.

Lok Adalats serve as an effective tool in India’s judicial landscape, providing an essential mechanism for resolving disputes amicably and efficiently. Their statutory backing and the associated benefits make them a vital component of the legal framework, reducing the backlog in courts and ensuring that justice is accessible to all segments of society.

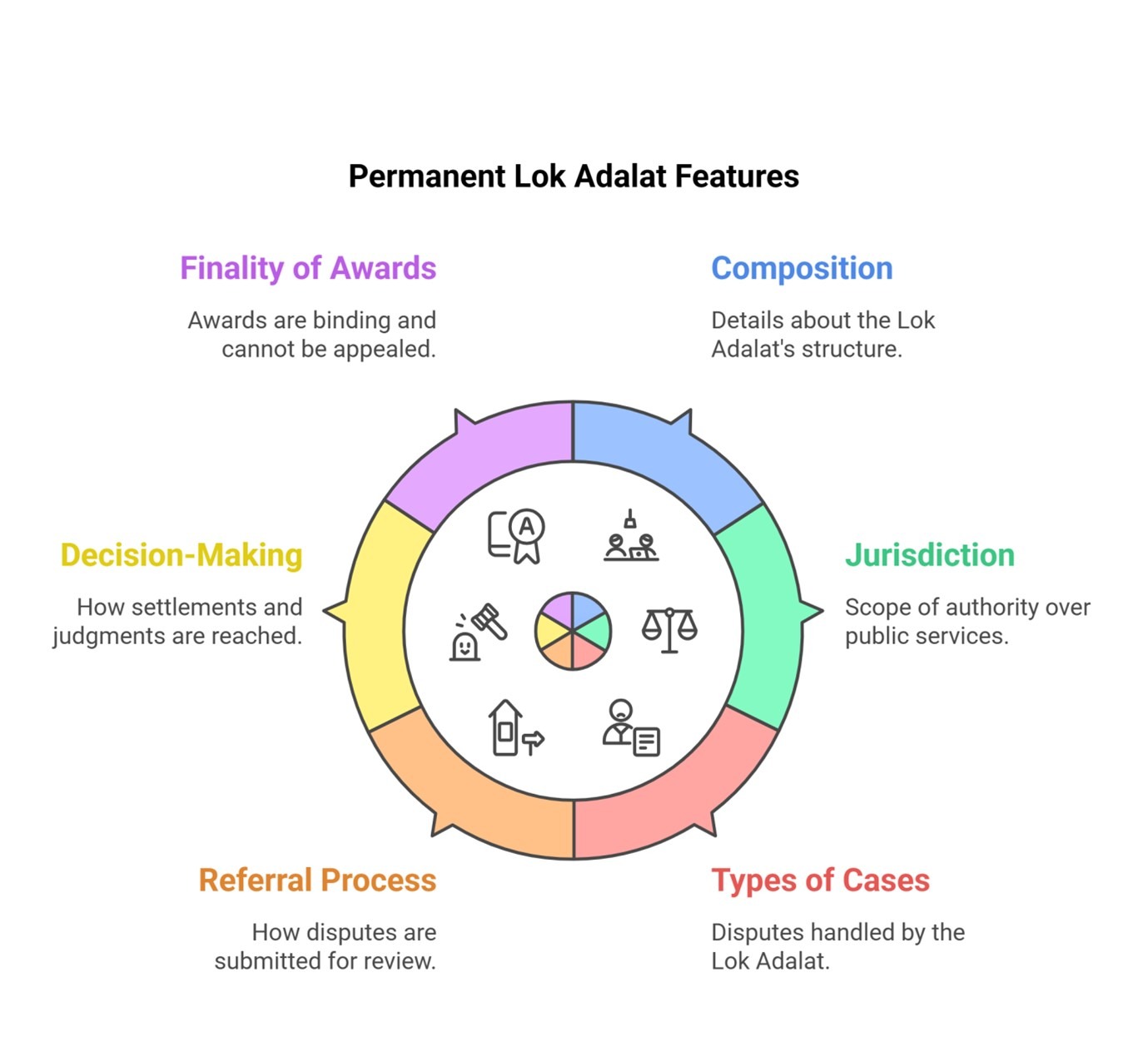

Permanent Lok Adalats

Establishment and Purpose

The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 was amended in 2002 to create Permanent Lok Adalats aimed specifically at settling disputes related to public utility services. The rationale for establishing these adalats includes:

- The original act sought to provide legal services to marginalized groups, ensuring everyone had access to justice.

- Lok Adalats have proven effective for amicably resolving disputes outside the traditional court system.

- A limitation of existing Lok Adalats was their reliance on compromise; if no settlement was reached, the case had to return to the regular courts, causing delays in justice.

- Urgent resolution of disputes in public utility services (e.g., telecommunications, electricity) was needed to alleviate the burden on regular courts.

- Establishing Permanent Lok Adalats would enable expedited clearing of cases, ideally at the pre-litigation stage.

Features of Permanent Lok Adalats

1. Composition:

- A Permanent Lok Adalat comprises a Chairman who is or has been a district or additional district judge, alongside two other individuals with relevant experience in public utility services.

2. Jurisdiction:

- It covers public utility services such as transportation, postal, telecommunication, electricity, water supply, sanitation, and healthcare.

- The pecuniary jurisdiction is set up to ₹10 lakhs (may be increased by the Central Government).

3. Types of Cases:

- Permanent Lok Adalats handle disputes related to public utility services, but do not entertain matters concerning non-compoundable offenses.

4. Referral Process:

- Disputes must be referred to the Permanent Lok Adalat before approaching any court. Once referred, no party can invoke court jurisdiction for the same dispute.

5. Decision-Making:

- If settlement is possible, the Permanent Lok Adalat formulates terms for the parties’ agreement. If no agreement is reached, the case is decided based on merits.

6. Finality of Awards:

- Awards made by the Permanent Lok Adalat are final, binding, and determined by a majority decision.

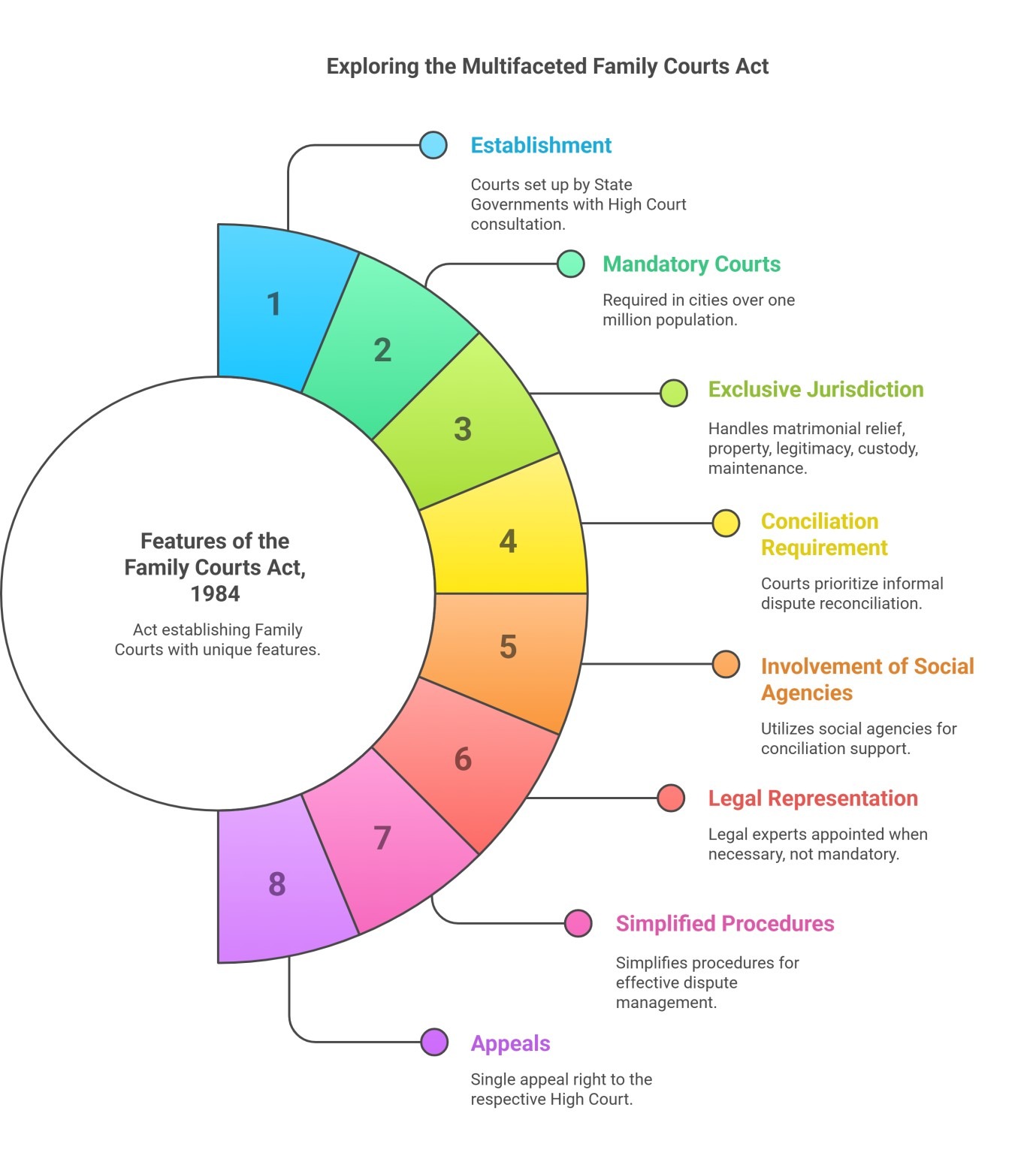

Family Courts

Establishment and Rationale

The Family Courts Act, 1984 was enacted to establish Family Courts aimed at promoting conciliation and facilitating prompt resolution of disputes related to marriage and family affairs. The key reasons for their establishment include:

- Advocacy from various organizations and women’s groups for dedicated forums to resolve family disputes through conciliation rather than strict adversarial procedures.

- The Law Commission’s 59th Report (1974) emphasized the need for a different approach in family disputes compared to other civil cases, advocating for reasonable settlement efforts before trials.

- Prior procedures were inadequately utilized; thus, establishing specialized Family Courts was deemed essential for effective dispute resolution.

Objectives

- To create a specialized court for family matters with the necessary expertise for expeditious disposal.

- To implement mechanisms for family dispute conciliation.

- To provide inexpensive and flexible remedies in an informal atmosphere.

Features of the Family Courts Act, 1984

1. Establishment: Family Courts are set up by State Governments with consultation from High Courts.

2. Mandatory Courts: States must establish Family Courts in cities or towns with populations over one million; others can be set up as deemed necessary.

3. Exclusive Jurisdiction: Family Courts handle matters such as:

- Matrimonial relief (nullity, divorce, restitution, validity)

- Spousal property

- Legitimacy declarations

- Guardianship and custody issues

- Maintenance for wives, children, and parents.

4. Conciliation Requirement: The courts must first try to reconcile disputes informally without rigid procedural constraints.

5. Involvement of Social Agencies: Family Courts can involve social welfare agencies, counselors, and experts during the conciliation process.

6. Legal Representation: While parties may not be entitled to legal representation, the Family Court can appoint a legal expert when necessary.

7. Simplified Procedures: The Family Courts simplify evidentiary rules and procedures to effectively manage disputes.

8. Appeals: Only one right of appeal exists, which lies with the respective High Court.

Both Permanent Lok Adalats and Family Courts have been established to provide quicker and more accessible justice. They emphasize conciliation, reduce burdens on regular courts, and aim to address the unique needs of specific types of disputes—public utility services and family affairs—enhancing the overall effectiveness of the Indian legal system.

Gram Nyayalayas

The Gram Nyayalayas Act, 2008 was enacted to set up Gram Nyayalayas (Village Courts) aiming to provide access to justice at the grassroots level, ensuring that citizens, especially the poor and disadvantaged, can secure justice without social, economic, or other barriers.

Reasons for Establishment

- Access to Justice: Global challenges persist regarding access to justice for poor and disadvantaged individuals. Article 39A of the Indian Constitution mandates that the legal system promotes justice and ensures free legal aid to those in need.

- Strengthening the Judicial System: The Indian Government has introduced various measures to enhance the judicial framework, including simplification of procedural laws and the establishment of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

- Law Commission’s Recommendations: The 114th Report of the Law Commission of India suggested setting up Gram Nyayalayas to provide speedy and affordable justice, particularly benefiting the common man in rural areas.

- Accessible Justice: The vision behind establishing Gram Nyayalayas is to offer prompt and affordable justice directly at the doorsteps of rural populations.

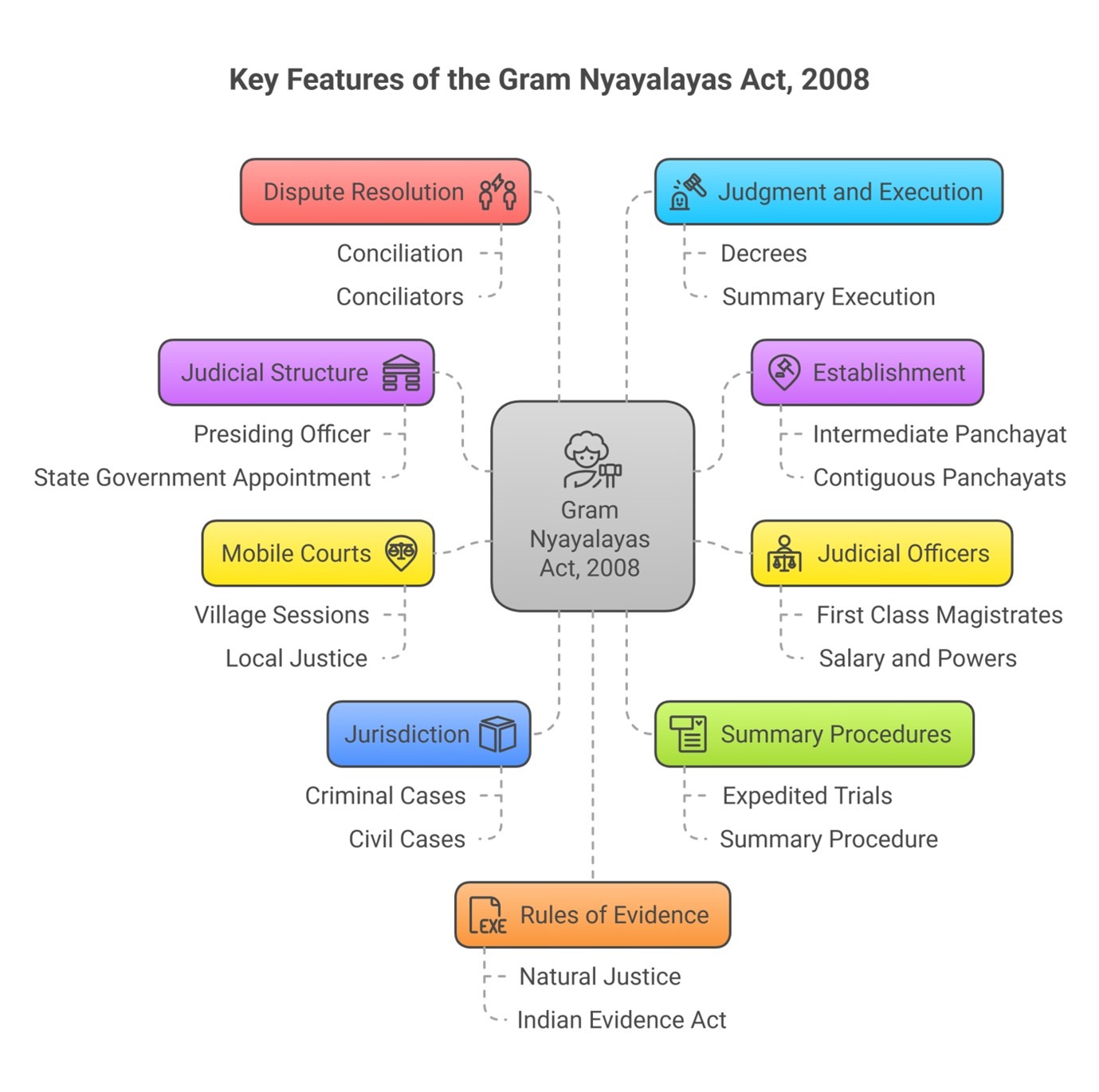

Key Features of the Gram Nyayalayas Act, 2008

- Judicial Structure: Gram Nyayalayas function as Judicial Magistrate of the First Class, led by a presiding officer (Nyayadhikari) appointed by the State Government in consultation with the High Court.

- Establishment: These courts are established for every intermediate Panchayat or groups of contiguous Panchayats in a district, facilitating justice in rural regions.

- Judicial Officers: The presiding Nyayadhikaris are judicial officers with the same powers and salary as First Class Magistrates.

- Mobile Courts: Gram Nyayalayas operate as mobile courts, holding sessions in villages to dispense justice locally.

- Jurisdiction: They can handle both criminal and civil cases as outlined in the First and Second Schedules of the Act.

- Summary Procedures: Criminal trials in Gram Nyayalayas follow a summary procedure, expediting the resolution process.

- Dispute Resolution: The Nyayalayas aim to resolve disputes through conciliation and can appoint conciliators to facilitate this process.

- Judgment and Execution: Judgments from Gram Nyayalayas are treated as decrees and follow a summary procedure for execution to minimize delays.

- Rules of Evidence: While not strictly bound by the rules of the Indian Evidence Act, the Nyayalayas are guided by principles of natural justice.

- Appeal Process:

- Appeals in criminal cases lie with the Court of Session, to be resolved within six months.

- Appeals in civil cases go to the District Court, also requiring a decision within six months.

11. Plea Bargaining: Provisions allow accused individuals to apply for plea bargaining.

Establishment and Funding

- The Central Government will fund the establishment of Gram Nyayalayas, covering non-recurring expenses up to ₹18 lakhs per court, allocated for construction, vehicles, and office equipment.

- Over 5,000 Gram Nyayalayas are projected to be established, with the Central Government providing approximately ₹1,400 crores in assistance to states and Union Territories.

Operational Challenges

Despite the establishment framework, several challenges face the operationalization of Gram Nyayalayas, including:

- Reluctance among police and state officials to utilize Gram Nyayalayas.

- Limited engagement from the legal community.

- Issues with concurrent jurisdiction between regular courts and Gram Nyayalayas.

- Availability of notaries and stamp vendors affecting procedural efficiency.

Gram Nyayalayas aim to enhance accessibility to justice and provide expedited, affordable legal solutions at the grassroots level in India. While their establishment represents a significant step towards improving the legal system, addressing operational challenges is crucial for their successful implementation and functioning.