Emergency Provisions

The emergency provisions are outlined in Part XVIII of the Indian Constitution, specifically Articles 352 to 360. These provisions empower the Central government to address any abnormal situations effectively. The rationale behind these provisions is to protect the sovereignty, unity, integrity, and security of the nation, as well as to uphold the democratic political system and the Constitution itself.

During an emergency, the Central government gains extensive powers, effectively placing states under its total control. This transition transforms the federal structure into a unitary system without requiring a formal constitutional amendment. This unique ability for the political system to shift from federal during normal times to unitary during an emergency distinguishes the Indian Constitution. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar noted in the Constituent Assembly that, unlike other federal systems (such as the American system), which remain rigidly federal regardless of circumstances, the Indian Constitution is flexible enough to operate as both unitary and federal as the situation demands.

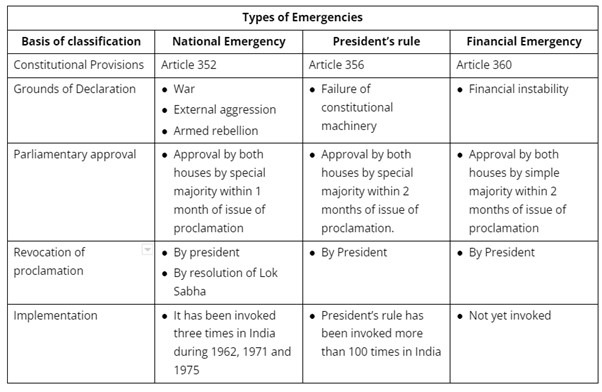

The Constitution recognizes three types of emergencies:

- National Emergency (Article 352): This occurs during war, external aggression, or armed rebellion. It is referred to as a “proclamation of emergency” in the Constitution.

- President’s Rule (Article 356): This emergency arises from the failure of constitutional machinery in the states, often termed “State Emergency” or “constitutional Emergency.” Notably, the term “emergency” is not specifically used in this context.

- Financial Emergency (Article 360): This type of emergency is declared when there is a threat to the financial stability or credit of India.

National Emergency

Grounds of Declaration

Under Article 352, the President can declare a national emergency when the security of India or a part of it is threatened by war, external aggression, or armed rebellion. The President can act even in anticipation of war or aggression if there is imminent danger. Additionally, the President can issue multiple proclamations based on war, external aggression, or armed rebellion, regardless of any prior proclamations in effect—this provision was added by the 38th Amendment Act of 1975.

When a national emergency is declared due to war or external aggression, it is referred to as an External Emergency. Conversely, if the emergency stems from armed rebellion, it is termed an Internal Emergency. A proclamation can apply nationwide or to a specific region; the 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 allows such an emergency to be limited to certain areas.

Initially, the Constitution allowed for a proclamation based on “internal disturbance,” but this term was deemed vague. Therefore, the 44th Amendment Act of 1978 replaced “internal disturbance” with “armed rebellion,” prohibiting declarations of national emergency on the former basis.

The President must issue a proclamation after receiving a written recommendation from the Cabinet, meaning that the emergency can only be declared with Cabinet approval, not solely on the Prime Minister’s advice. In 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi advised the President to declare an emergency without consulting her Cabinet, which was informed afterward. The 44th Amendment Act of 1978 established this safeguard to prevent unilateral decisions by the Prime Minister.

The 38th Amendment Act of 1975 initially made national emergency declarations immune from judicial review, but this provision was repealed by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978. The Supreme Court later ruled in the Minerva Mills case (1980) that a national emergency declaration can be challenged in court if it is based on bad faith or irrelevant, absurd facts.

Parliamentary Approval and Duration

The proclamation of emergency must be approved by both Houses of Parliament within one month of its issuance. This approval period was shortened from two months by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978. If the emergency is declared while the Lok Sabha is dissolved, it remains in effect for 30 days after the first sitting of the reconstituted Lok Sabha, provided the Rajya Sabha has approved it in the meantime.

Once both Houses approve the emergency, it lasts for six months and may be extended indefinitely with biannual parliamentary approval. This requirement for periodic approval was also introduced by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978, as previously, an emergency could last as long as the Cabinet desired after initial parliamentary approval.

If the Lok Sabha is dissolved during the six-month period without further approval, the proclamation continues until 30 days following the Lok Sabha’s reconvening, contingent upon Rajya Sabha approval.

Every resolution to approve or extend the emergency must be passed by a special majority, defined as: (a) A majority of the total membership of the House, and (b) At least two-thirds of the members present and voting.

This requirement for a special majority was established by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978, whereas earlier resolutions could be passed by a simple majority.

Revocation of Proclamation

A proclamation of emergency can be revoked at any time by the President through a subsequent proclamation that does not require parliamentary approval. However, if the Lok Sabha passes a resolution disapproving the continuation of the emergency, the President is obligated to revoke the proclamation. This safeguard was introduced by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978, which previously allowed the President to revoke a proclamation unilaterally without Lok Sabha oversight.

Additionally, the 44th Amendment provides that if one-tenth of Lok Sabha members submit a written notice to the Speaker (or the President if the House is not in session), a special sitting must be convened within 14 days to consider a resolution disapproving the proclamation’s continuation.

There are two key differences between a resolution of disapproval and a resolution approving the continuation of a proclamation:

- The former requires approval only from the Lok Sabha, while the latter must be passed by both Houses of Parliament.

- The disapproval resolution needs only a simple majority to pass, whereas the approval resolution requires a special majority.

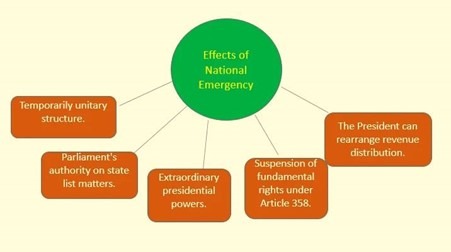

Effects of National Emergency

A proclamation of emergency has significant and far-reaching effects on the political system, which can be categorized as follows:

- Effect on Centre-State Relations

- Effect on the Life of Lok Sabha and State Assemblies

- Effect on Fundamental Rights

Effect on Centre-State Relations

During a national emergency, the regular dynamics of Centre-state relations undergo significant changes, which can be analyzed in three areas: executive, legislative, and financial.

(a) Executive: The Centre’s executive power expands to include directing states on how to exercise their executive powers. While normally the Centre can issue directions on specified matters, during an emergency, it can direct states on any issue. Although state governments remain in place, they fall under the complete authority of the Centre.

(b) Legislative: Parliament gains the ability to legislate on matters within the State List during an emergency. Although a state legislature’s legislative power is not suspended, it becomes subordinate to Parliament’s overriding authority. This situation represents a shift from a federal to a unitary structure. Laws enacted by Parliament on state subjects during this period will become ineffective six months after the emergency concludes. Furthermore, the President may issue ordinances on state subjects if Parliament is not in session during the emergency.

(c) Financial: The President can alter the constitutional distribution of revenues between the Centre and the states during an emergency. This allows for the reduction or cancellation of financial transfers from the Centre to the states, effective until the end of the financial year in which the emergency ends. All such orders must be presented to both Houses of Parliament.

The 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 extended the effects of executive and legislative powers during an emergency not only to the state where the emergency is declared but also to other states.

Effect of National Emergency on the Life of the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies

During a National Emergency, the term of the Lok Sabha can be extended beyond its usual five-year duration by a law of Parliament, with extensions allowed for one year at a time. However, this extension cannot exceed six months after the emergency ends. For example, the Fifth Lok Sabha (1971–1977) saw its term extended twice by one year each time.

Similarly, a state legislative assembly’s normal tenure of five years can be extended by one year at a time during a national emergency, subject to the same six-month post-emergency limit.

Effect on Fundamental Rights

Articles 358 and 359 of the Constitution describe the impact of a National Emergency on Fundamental Rights.

(a) Suspension of Fundamental Rights under Article 19

- During Emergency: Article 358 automatically suspends the six Fundamental Rights under Article 19 during a national emergency. The state can enact laws or take executive actions that infringe upon these rights without challenge. Once the emergency ends, Article 19 is automatically revived. Laws inconsistent with Article 19 cease to have effect, although actions taken during the emergency remain unchallengeable.

- 44th Amendment Restrictions: The 44th Amendment Act of 1978 restricted Article 358, allowing suspension of Article 19 rights only during emergencies due to war or external aggression, not armed rebellion. Laws protected are only those related to the emergency, and only corresponding executive actions are protected.

(b) Suspension of Other Fundamental Rights

- Presidential Authority: Article 359 allows the President to suspend the right to approach courts for enforcing specified Fundamental Rights during a national emergency. While rights themselves are not suspended, seeking court enforcement is. The suspension pertains only to rights specified in a Presidential Order and can be limited to specific areas or durations, subject to parliamentary approval.

- Post-Order Effects: Any laws or actions taken during the order’s operation are immune from challenge based on inconsistency with specified rights. Once the order expires, inconsistent laws no longer have effect, but actions taken under the order remain unchallengeable.

- 44th Amendment Restrictions: The 44th Amendment Act limited Article 359 by keeping the rights under Articles 20 (protection in respect of conviction for offenses) and 21 (right to life and personal liberty) enforceable even during an emergency. Only laws relating to the emergency, along with relevant executive actions, are protected.

These provisions aim to balance the need for security during emergencies with the protection of fundamental rights.

Distinction Between Articles 358 and 359

The differences between Articles 358 and 359 of the Indian Constitution are as follows:

1. Scope of Rights Affected

- Article 358 applies specifically to the Fundamental Rights under Article 19.

- Article 359 pertains to the suspension of enforcement of any Fundamental Rights specified by the Presidential Order.

2. Automatic Suspension vs. Presidential Action

- Article 358 automatically suspends the rights under Article 19 once a National Emergency is declared.

- Article 359 requires Presidential action to suspend the enforcement of specified Fundamental Rights.

3. Type of Emergency

- Article 358 is activated only during an External Emergency (declared due to war or external aggression), not during an Internal Emergency (due to armed rebellion).

- Article 359 can be applied during both External and Internal Emergencies.

4. Duration of Suspension

- Article 358 affects Article 19 rights for the entire duration of the Emergency.

- Article 359 allows the President to specify the period of suspension, which may be the entire duration of the Emergency or shorter.

5. Geographical Extent

- Article 358 is applicable to the entire country.

- Article 359 can be limited to the entire country or specific parts.

6. Complete vs. Partial Suspension

- Article 358 completely suspends Article 19 rights.

- Article 359 does not allow for the suspension of the enforcement of Articles 20 and 21.

7. Legislative and Executive Actions

- Article 358 permits the State to enact laws or take actions inconsistent with Article 19 rights.

- Article 359 allows for laws or actions inconsistent with specified rights under a Presidential Order.

Similarity: Both articles provide immunity from legal challenges only for laws related to the Emergency and protect executive actions taken under such laws.

Declarations of National Emergency

National Emergency has been declared in India three times:

- 1962: The first declaration occurred in October 1962 due to Chinese aggression in the NEFA region (now Arunachal Pradesh) and lasted until January 1968. This covered the subsequent conflict with Pakistan in 1965 without a new declaration.

- 1971: The second declaration was made in December 1971 following Pakistan’s attack, and it overlapped with the third declaration.

- 1975: The third declaration occurred in June 1975 due to “internal disturbance,” where individuals were inciting forces against their duties. This was the most controversial, leading to widespread criticism and the loss of power for Indira Gandhi’s Congress Party in the 1977 elections.

Aftermath and Reforms

The 1975 Emergency led to significant controversy and criticisms of Emergency powers misuse. In response, the 44th Amendment Act of 1978 introduced safeguards against such abuse following recommendations by the Shah Commission, which concluded the Emergency was unjustified. These reforms aimed to prevent the recurrence of similar circumstances.

President’s Rule

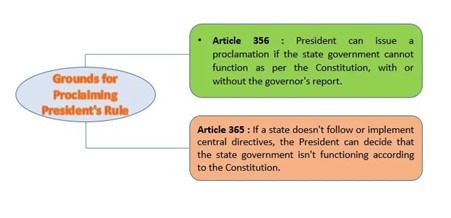

Grounds of Imposition

Article 355 of the Indian Constitution imposes a duty on the Central Government to ensure that the governance of every state aligns with the Constitution’s provisions. When a state fails to comply, the Centre may assume control under Article 356, commonly known as ‘President’s Rule’ or sometimes as ‘State Emergency’ or ‘Constitutional Emergency.’

President’s Rule can be invoked based on two grounds:

- Article 356: The President can issue a proclamation if satisfied that the state government cannot be conducted per the Constitution’s provisions. This decision can be based on a report from the state’s governor or independently, even without such a report.

- Article 365: This article allows the President to assume governance if a state fails to follow or implement directions from the Centre, prompting a belief that the state government cannot function according to Constitutional provisions.

Parliamentary Approval and Duration

A proclamation of President’s Rule must be ratified by both Houses of Parliament within two months. If issued when the Lok Sabha is dissolved or dissolves during this period without approval, the proclamation remains valid for 30 days following the Lok Sabha’s reconstitution, assuming the Rajya Sabha approves in the meantime.

Once approved, President’s Rule can last for six months and can be extended for up to three years with parliamentary approval every six months. Should the Lok Sabha dissolve during a six-month period without extending President’s Rule, the proclamation remains valid for 30 days after the Lok Sabha’s reconstitution, if extended by the Rajya Sabha in the interim.

Approvals for President’s Rule or its extension require a simple majority in both Houses, meaning more supporting votes than opposing votes from those present and voting.

Restrictions and Conditions

The 44th Amendment Act of 1978 introduced conditions constraining Parliament’s ability to extend President’s Rule beyond one year. Extensions beyond one year, by six-month intervals, are allowed only if:

- A National Emergency is in effect, either nationwide or in the specific state.

- The Election Commission certifies that elections to the state’s legislative assembly cannot be conducted due to specific difficulties.

The President may revoke President’s Rule at any time through a new proclamation, which does not require parliamentary approval.

Consequences of President’s Rule

When President’s Rule is imposed in a state, the President gains several extraordinary powers:

1. Assumption of State Functions

- The President can take over the functions of the state government as well as the powers vested in the governor or any other state executive authority.

2. Legislative Authority

- The President can declare that the powers of the state legislature will be exercised by Parliament.

3. Other Necessary Actions

- The President can take any necessary measures, including suspending constitutional provisions related to any body or authority within the state.

As a result of these powers, when President’s Rule is enforced, the President dismisses the state council of ministers, which is led by the chief minister. The governor of the state administers affairs on behalf of the President, assisted by the chief secretary or advisors appointed by the President. This action is why the proclamation under Article 356 is often referred to as the imposition of “President’s Rule.”

Actions Taken during President’s Rule

When the state legislature is suspended or dissolved, the following actions can occur:

1. Delegation of Legislative Power

- Parliament may delegate the authority to make laws for the state to the President or to any other authority specified by him.

2. Law-Making Authority

- Parliament, or in the case of delegation, the President or the specified authority can enact laws that confer powers and impose duties on the Centre or its officials.

3. Expenditure Authorization

- The President can authorize expenditure from the state consolidated fund when the Lok Sabha is not in session, pending its approval by Parliament.

4. Promulgation of Ordinances

- The President can issue ordinances for the governance of the state when Parliament is not in session.

Continuity of Laws

Any law enacted by Parliament, the President, or another specified authority during President’s Rule remains in effect even after the proclamation ends. This implies that such laws do not expire when the President’s Rule is lifted but can be repealed, amended, or re-enacted by the state legislature.

Limitations on Presidential Powers

- It is important to note that the President cannot assume the powers of the concerned state high court or suspend constitutional provisions related to it. The constitutional position, status, powers, and functions of the state high court remain intact, even during the imposition of President’s Rule.

Use of Article 356

- Since the introduction of the Constitution in 1950, President’s Rule under Article 356 has been imposed over 125 times, averaging approximately twice a year. This frequent application has led to significant scrutiny, especially since there have been instances where President’s Rule was applied in an arbitrary manner for political or personal motives. As a result, Article 356 has emerged as one of the most controversial and criticized provisions within the Constitution.

Comparison of National Emergency and President’s Rule

Aspect | National Emergency (Article 352) | President’s Rule (Article 356) |

Grounds for Proclamation | Can be proclaimed only when the security of India or any part is threatened by war, external aggression, or armed rebellion. | Can be proclaimed when the government of a state cannot operate in accordance with the Constitution for reasons unrelated to war, aggression, or rebellion. |

Functioning of State Government | During its operation, the state executive and legislature continue to function and exercise their powers under the Constitution. The Centre gains concurrent powers of administration and legislation in the state. | During its operation, the state executive is dismissed, and the state legislature is either suspended or dissolved. The President administers the state through the governor, and Parliament makes laws for the state, assuming both executive and legislative powers. |

Law-Making Powers | Under a National Emergency, Parliament can make laws on subjects in the State List directly. | Under President’s Rule, Parliament can delegate law-making powers for the state to the President or another designated authority. Typically, laws are made in consultation with Parliament members from that state, referred to as President’s Acts. |

Duration of Operation | No maximum period prescribed; can continue indefinitely with Parliament’s approval every six months. | Maximum duration is three years; must end after this period, and normal constitutional machinery must be restored in the state. |

Impact on Relationship with the Centre | Modifies the relationship between the Centre and all states. | Modifies the relationship between only the state under President’s Rule and the Centre. |

Parliamentary Approval for Proclamation | Requires a resolution approving the proclamation or its continuance to be passed by a special majority. | Requires a resolution approving the proclamation or its continuance to be passed by a simple majority. |

Impact on Fundamental Rights | Affects Fundamental Rights of citizens. | Has no effect on Fundamental Rights of citizens. |

Revocation Provisions | Lok Sabha can pass a resolution for its revocation. | Can be revoked by the President independently; no provision for Lok Sabha involvement in revocation. |

This comparison highlights the key distinctions between National Emergency and President’s Rule, illustrating the scope, implications, and processes involved in each situation.

Use of Article 356: The Case of President’s Rule

President’s Rule was first imposed in Punjab in 1951, and since then, it has been enacted in nearly all states at least once. The details of these implementations can be found in Table 16.2 at the end of this chapter.

After the internal emergency, general elections for the Lok Sabha were held in 1977, resulting in the Congress Party’s loss and the rise of the Janata Party led by Morarji Desai. The new government imposed President’s Rule in nine states where the Congress Party held power, citing that the state assemblies no longer reflected the electorate’s wishes. Subsequently, when the Congress Party returned to power in 1980, it imposed President’s Rule in the same nine states on identical grounds.

In 1992, President’s Rule was applied in three states governed by the BJP—Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Rajasthan—by the Congress Party, claiming that these states were not sincerely enforcing a central ban on certain religious organizations. The Supreme Court, in the landmark Bommai Case (1994), upheld the validity of this proclamation on the principle that secularism is a ‘basic feature’ of the Constitution. However, the Court did not uphold President’s Rule in Nagaland (1988), Karnataka (1989), and Meghalaya (1991).

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, during the Constituent Assembly debates, expressed his hope that the drastic powers granted by Article 356 would remain a “dead letter” and be used only as a last resort. He remarked, “The intervention of the Centre must be deemed to be barred, because that would be an invasion on the sovereign authority of the province (state).” He emphasized that such powers should only be invoked with considerable caution.

Despite these intentions, the reality has shown that what was expected to be a rarely used provision has instead become a frequently applied mechanism against various state governments and assemblies. H.V. Kamath, a Constituent Assembly member, remarked, “Dr. Ambedkar is dead, and the Articles are very much alive.”

Scope of Judicial Review

The 38th Amendment Act of 1975 initially made the President’s satisfaction regarding the invocation of Article 356 final and beyond judicial scrutiny. However, this provision was subsequently revoked by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978, reinforcing that the President’s satisfaction is subject to judicial review.

In the Bommai Case (1994), the Supreme Court established several key propositions concerning the imposition of President’s Rule under Article 356:

- The presidential proclamation imposing President’s Rule is subject to judicial review.

- The President’s satisfaction must be based on relevant material; if it relies on irrelevant or extraneous grounds, or if deemed malafide or perverse, the court can nullify the action.

- The burden is on the Centre to demonstrate that relevant material justifies the imposition of President’s Rule.

- The court cannot evaluate the correctness or adequacy of the material but can examine its relevance to the action taken.

- Should the court determine the presidential proclamation unconstitutional, it has the authority to restore the dismissed state government and revive the state legislative assembly if it was suspended or dissolved.

- A state legislative assembly can only be dissolved after Parliament approves the presidential proclamation. Until then, the President can only suspend the assembly. If Parliament does not approve, the assembly will be reactivated.

- Secularism is deemed one of the ‘basic features’ of the Constitution, making a state government pursuing anti-secular policies susceptible to action under Article 356.

- Any question regarding a state government losing confidence in the legislative assembly must be resolved on the House floor; until then, the ministry should not be removed.

- A new political party in power at the Centre cannot dismiss ministries formed by other parties within the states.

- The powers under Article 356 are exceptional and should only be used in response to specific situations requiring such drastic measures.

These principles underscore the importance of protecting the federal structure of governance while permitting the Centre to intervene in state affairs under extraordinary circumstances.

Cases of Proper and Improper Use of Article 356

Based on the Sarkaria Commission’s report on Centre-state relations (1988) and reinforced by the Supreme Court in the Bommai case (1994), guidelines have been established regarding the proper and improper exercise of power under Article 356, particularly concerning the imposition of President’s Rule in a state.

Situations Where Imposition of President’s Rule Is Proper:

- Hung Assembly: When no party secures a majority after general elections to the assembly.

- Declining Majority Party: If the party with a majority decides not to form a ministry and the governor cannot find a coalition government commanding a majority.

- Resignation After Defeat: When a ministry resigns after losing a vote in the assembly, and no other party is willing or able to form a government with majority support.

- Disregarding Constitutional Directives: If the state government disregards a constitutional direction given by the Central government.

- Internal Subversion: In cases where the state government is deliberately acting against the Constitution or law, or is inciting a violent revolt.

- Physical Breakdown: When the government knowingly refuses to fulfill its constitutional responsibilities, thus endangering the security of the state.

Situations Where Imposition of President’s Rule Is Improper:

- Immediate Resignation Without Exploration: When a ministry resigns or is dismissed after losing majority support, and the governor recommends President’s Rule without exploring the possibility of forming an alternative government.

- Governor’s Unidirectional Assessment: If the governor independently assesses the ministry’s support in the assembly and recommends President’s Rule without allowing the ministry to demonstrate its majority on the assembly floor.

- Defeat in General Elections: When the ruling party, despite holding majority support in the assembly, suffers a significant defeat in the general elections for the Lok Sabha (e.g., in 1977 and 1980).

- Minor Internal Disturbances: Internal disturbances that do not rise to the level of internal subversion or physical breakdown.

- Allegations of Maladministration: General claims of maladministration or corruption against the ministry or significant financial exigencies within the state should not automatically warrant President’s Rule.

- No Prior Warning: If the state government does not receive prior warning to rectify any issues (except in cases of extreme urgency that could lead to disastrous consequences).

- Intra Party Issues: Where the power is misused to resolve internal party conflicts or for purposes that do not align with the reasons for which Article 356 has been conferred.

These distinctions are critical in ensuring that the imposition of President’s Rule is justified and not misused for political gains or arbitrary reasons.

Financial Emergency

Article 360 of the Indian Constitution empowers the President to proclaim a Financial Emergency if he is satisfied that the financial stability or credit of India, or any part of its territory, is threatened.

The 38th Amendment Act of 1975 initially made the President’s satisfaction regarding the declaration of a Financial Emergency final and not subject to judicial review. However, this provision was removed by the 44th Amendment Act of 1978, indicating that the President’s satisfaction can now be subject to judicial scrutiny.

Parliamentary Approval and Duration A proclamation of Financial Emergency must be approved by both Houses of Parliament within two months of its issuance. If the proclamation is issued when the Lok Sabha is dissolved or if the Lok Sabha dissolves within that two-month period without approval, the proclamation remains in effect for 30 days from the first sitting of the reconstituted Lok Sabha, provided that the Rajya Sabha has approved it in the meantime.

Once both Houses of Parliament approve the proclamation, the Financial Emergency continues indefinitely until revoked. This means:

- There is no maximum duration prescribed for its operation.

- There is no need for repeated parliamentary approval for its continuation.

A resolution approving the Financial Emergency can be passed by either House of Parliament with a simple majority, meaning more members present and voting in favor than against.

The President can revoke a proclamation of Financial Emergency at any time through a subsequent proclamation, which does not require parliamentary approval.

Effects of Financial Emergency

The declaration of a Financial Emergency results in several significant consequences:

- Central Authority Over States: The executive authority of the Centre extends to issuing directions to states to adhere to specified financial propriety and any other necessary directives that the President deems adequate.

- Restrictions on Financial Matters: These directives may include provisions for:

- The reduction of salaries and allowances for specific classes of personnel serving in the state.

- The reservation of all money bills or financial bills for the President’s consideration after they have been passed by the state legislature.

- Salary Reductions: The President may also direct reductions in the salaries and allowances of:

- All or specific classes of personnel serving the Union.

- Judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts.

Thus, during a financial emergency, the Centre gains comprehensive control over fiscal matters in the states. H.N. Kunzru, a member of the Constituent Assembly, highlighted that the provisions for a financial emergency could pose a significant threat to the financial autonomy of the states. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar commented on this provision’s rationale during the Constituent Assembly discussions, noting its resemblance to the U.S. National Recovery Act of 1933, which aimed to address economic and financial difficulties stemming from the Great Depression.

Despite financial crises in the country, such as the one in 1991, no Financial Emergency has ever been declared.

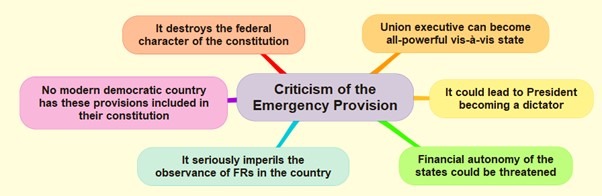

Criticism of the Emergency Provisions

Members of the Constituent Assembly expressed several criticisms regarding the inclusion of emergency provisions in the Constitution, raising concerns about their potential implications:

- Threat to Federal Character: Critics argued that the emergency provisions would undermine the federal structure of the Constitution, leading to an all-powerful Union government.

- Concentration of Power: There were apprehensions that such provisions would concentrate the powers of both the Union and state governments entirely in the hands of the Union executive.

- Risk of Dictatorship: There was a fear that the President could become a dictator, wielding excessive powers without sufficient checks.

- Erosion of Financial Autonomy: Critics pointed out that the financial autonomy of the states would be undermined, leading to greater dependency on the Centre.

- Meaningless Fundamental Rights: Concerns were raised that the emergency provisions would render Fundamental Rights meaningless, ultimately jeopardizing the democratic foundations of the Constitution.

- H.V. Kamath expressed his worries by stating, “I fear that by this single chapter we are seeking to lay the foundation of a totalitarian state, a police state, a state completely opposed to all the ideals and principles that we have held aloft during the last few decades, a State where the rights and liberties of millions of innocent men and women will be in continuous jeopardy.” He emphasized that if peace were achieved, it would be a hollow semblance devoid of freedom.

- K.T. Shah criticized the emergency provisions as “a chapter of reaction and retrogression,” stating that they aimed to equip the Centre with special powers against the states and the government against the people. He lamented that with such provisions, only the name of liberty or democracy would remain under the Constitution.

- T.T. Krishnamachari warned that these provisions could enable the President and the Executive to exercise a form of constitutional dictatorship. Similarly, H.N. Kunzru indicated that the financial emergency provisions posed a significant threat to the financial autonomy of the states.

However, some members defended the inclusion of emergency provisions. Sir Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar described them as “the very life-breath of the Constitution,” and Mahabir Tyagi suggested they would act as a “safety valve,” helping to maintain constitutional order.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, while defending the emergency provisions, acknowledged the potential for misuse, stating, “I do not altogether deny that there is a possibility of the Articles being abused or employed for political purposes.”

These debates reflect the complex perspectives on the necessity and implications of emergency provisions within the constitutional framework.

Articles Related to Emergency Provisions at a Glance

Article No. | Subject-matter |

352 | Proclamation of Emergency |

353 | Effect of Proclamation of Emergency |

354 | Application of provisions relating to the distribution of revenues while a Proclamation of Emergency is in operation |

355 | Duty of the Union to protect states against external aggression and internal disturbance |

356 | Provisions in case of failure of constitutional machinery in states |

357 | Exercise of legislative powers under proclamations issued under Article 356 |

358 | Suspension of provisions of Article 19 during Emergencies |

359 | Suspension of the enforcement of the rights conferred by Part III during Emergencies |

359A | Application of this part to the state of Punjab (Repealed) |

360 | Provisions as to Financial Emergency |

This table summarizes key articles related to the emergency provisions in the Indian Constitution, outlining their primary focus and purpose.